Research Report

The Recovery of the Longfellow Landscape

by Mona McKindley and Scott Law

Efforts to restore the landscape of Longfellow National Historic Site are well underway.(1) The site is located on 1.98 acres in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and includes the 18th-century house the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow received as a wedding present in 1843. While only the core of the original 1759 estate remains, many of the 18th-century landscape features are still evident, such as the Brattle Street forecourt of American elms framing the house, the terraces, and the front fence. Longfellow and his heirs were also successful in preserving parcels of land stretching from the house proper to the Charles River.

It was the river frontage that first gave the property its historic cachet. Its strategic location captured the attention of General George Washington, who lived and made his headquarters here during the Siege of Boston in 1775-76. The Washington connection attracted Longfellow to the property, who, once there, added his own touches to the landscape, including a formal flower garden planted behind the house in 1847. Consisting of eight beds in all—four tear-drop shaped beds and four triangular ones at the corners—the garden resembled a Persian carpet in design, with flowers surrounded by a low border of boxwood.(2)

Creating the Colonial Revival-era Garden

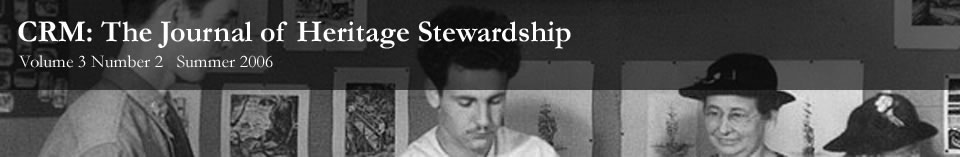

Longfellow's children and the Longfellow House Trust oversaw the preservation of the house and grounds for more than a century. The poet's daughter Alice nurtured the site's historical connections with Washington and her father in the hopes of establishing a memorial to the two men. While the property was under her care (from 1882 to 1928), portions of the grounds were overlaid with a Colonial Revival landscape that mingled formal axes and vistas with the over-grown, loosely pruned varieties of native plants found in less formal gardens.(3) The Colonial Revival penchant for the beautiful and quaintly old-fashioned is exemplified in Longfellow's formal garden, which was expanded in 1904 and again in 1925 by two of the leading landscape architects of the day, Martha Brookes Hutcheson and Ellen Biddle Shipman.(Figure 1)

|

Figure 1. HABS produced this plan of the Longfellow formal garden in the 1930s. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

In 1904, Hutcheson refurbished the flower beds Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had created, re-setting the boxwood, adding an elaborate pergola to the east, installing a lattice garden fence with ornamental gates, and reorienting a lattice screen with pediment.(4) The pergola, finials, and lattices called to mind the architecture of the colonial era in their detailing, whereas the arrangement of hedges, walls, pathways, vine-covered trellis screening the stable, and other garden features reflected Hutcheson's personal, more contemporary design preferences. The pergola offered shade and provided a focal point for an otherwise "uninteresting distance," to use Hutcheson's words. A loosely defined border of plantings softened the transition from the garden to the field beyond.(5)

Hutcheson had transformed Longfellow's flower garden into a well-defined outdoor room. In 1925, Alice Longfellow recruited another prominent landscape architect, Ellen Biddle Shipman, to rejuvenate the plantings. Shipman added popular flowers from the colonial era and maintained flowers favored earlier by Henry Longfellow. She surrounded the 1904 garden with rectangular beds of roses and other flowering shrubs and introduced columnar arborvitae, ornamental cherry trees, and dwarf crabapples for a more dramatic, three-dimensional effect.(6)

By the end of the 20th century, many of the historic design features of the Longfellow landscape had either been altered or had disappeared or deteriorated. In the 1930s, for example, a hurricane destroyed the large pergola in the formal garden (the pergola was never rebuilt). Around 1970, the garden itself was reduced to one-third its original size for ease of maintenance. As a result of these changes, the landscape appeared spare and institutional compared to the profusely planted, romantic one known and loved by the Longfellows.

Restoring the Longfellow Landscape

The restoration of the Longfellow landscape has been ongoing since 2000, and the Colonial Revival-era garden is one phase of this effort. Tasks have included the removal of invasive plants, the restoration of pathways and planting beds, the rehabilitation or replanting of screen trees and ornamental shrubs along the northern and eastern boundary lines of the property, the reconstruction of the large pergola, the reproduction of garden pots and wooden bench, the realignment of the garden's Hutcheson-era lattice fence, and the re-installation of the garden gates.

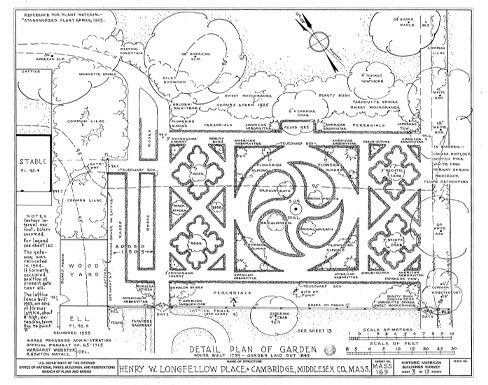

Before the last task could be completed, the fence and gates had to be reconstructed. National Park Service woodcrafters created a new "old" fence based on surviving architectural fragments and graphic evidence. Early Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) drawings of the gardens at the Longfellow House provided many of the specifications.(Figure 2) The lattice fencing was crafted out of mahogany, a wood noted for its water resistant qualities. The lattice was rebuilt with specially made rails and thin mahogany strips. The post skirts and caps were carefully beveled and hand-sanded to shed water. The HABS drawings and an architectural fragment also guided the design and production of four carved mahogany urns for adorning the post caps at the gates.

|

Figure 2. This detail from a 1930s HABS drawing was instrumental in recreating the fence at Longfellow National Historic Site. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.) |

Unlike the lattice fence and posts, the Colonial Revival-era pine gates needed only spot repairs. In sections where the wood had rotted, new pieces made of pine were cut to fit and glued into place.(Figure 3) In instances where the extant latches and hinges were brittle or cracked, the hardware was reproduced in a more pliable bronze alloy. Both the fence and gates received coats of paint as an additional measure of protection against the elements. Preliminary studies revealed the original fence footings, which made an historically accurate realignment of the fence and repositioning of the gate posts possible.(7)

|

Figure 3. This view shows the repairs made to the gate posts. (Courtesy of Longfellow National Historic Site.) |

Once the fence was in place, the National Park Service grounds crew planted a large collection of custom-propagated heirloom roses in the west end of the garden, along with over 2,000 fragrant, heirloom perennials, in an attempt to recreate the garden's 1925 appearance. More than 300 heirloom annuals and 1,075 bulbs—tulips, daffodils, dahlias, and gladiolas—will be planted by next spring. Once complete, the Longfellow garden, with its profuse plantings and exemplary Colonial Revival features, will flourish once more.

About the Authors

Mona McKindley is an estate gardener and Scott Law is a woodcrafter at the Longfellow National Historic Site in Cambridge, Massachusetts. To learn more about the landscape recovery project, contact them at mona_mckindley@nps.gov and scott_law@nps.gov.

Notes

1. The restoration of the Longfellow formal garden is based on the research, analysis, and recommendations of a three-volume Cultural Landscape Report compiled between 1991 and 1997. Project support was provided by the Friends of the Longfellow House, a 2003 "Save America's Treasures" grant, and public and private donations. Project participants not mentioned elsewhere in the report included Steve Law and Leonard Giannetti of the National Park Service.

2. Catherine Evans, Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site vol. 1: Site History and Existing Conditions (National Park Service Cultural Resource Management Program, 1993), 44, 63-64.

3. Alan Axelrod, ed., The Colonial Revival in America (New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 1985); Mac Griswold and Eleanor Weller, The Golden Age of American Gardens: Proud Owners, Private Estates, 1890-1940 (New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers, 1992); and Susan L. Hitchcock, "The Colonial Revival Gardens of Hubert Bond Owens" (master's thesis, University of Georgia, 1997).

4. Evans, pp. 63-65; Martha Brookes Hutcheson, The Spirit of the Garden (1923; Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2001): 104-05; "Henry Longfellow Place" (HABS No. MA-169), Historic American Buildings Survey, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

5. Evans, 63-69; Hutcheson, 104-05, 155-58.

6. Evans, 71; Judith B. Tankard, The Gardens of Ellen Biddle Shipman (Sagaponack, NY: Sagapress in association with the Library of American Landscape History, 1996).

7. Marrying the original garden gates to the new lattice fence posed a challenge that the archeologists answered with their investigation of the formal garden. The National Park Service grounds crew had already felled two large crabapples that had grown into the fence, and archeologists determined that the tree roots could also be removed from the fence line without adverse effects. In 2004, Longfellow National Historic Site contracted with Earth Tech, whose archeologists worked under Stephen Pendery, chief archeologist for the National Park Service's Northeast Region, to locate the original postholes and remove old footings in preparation for the installation of the new fence.

By spring 2004, test-fitting of the posts and fence installation were underway. Each post consisted of a steel interior member set into concrete footings and covered by a wood sleeve. Care was taken that the wood post with its skirt did not touch the soil. By late summer, the posts were in place. As the sections of the fence went in, the archeological trench was backfilled. This process continued into the next spring. See Stephen Pendery, Management Summary Longfellow Garden Excavations, 2001-02 (Lowell, MA: Northeast Region Archeology Program, March 2003).