NPS Photo / N Scarborough Summary"Uplift" is when a landscape is raised above others, usually over a large area. Several uplifts happened in this area across the eons. The uplift that formed the Uncompahgre Plateau (which includes modern Pinyon Mesa and Unaweep Canyon) activated - or was activated by - the Redlands Fault. We rise hundreds of feet above the Grand Valley because of this most recent uplift. Movement of tectonic plates, the pieces that make up Earth's crust, is what causes this uplift.

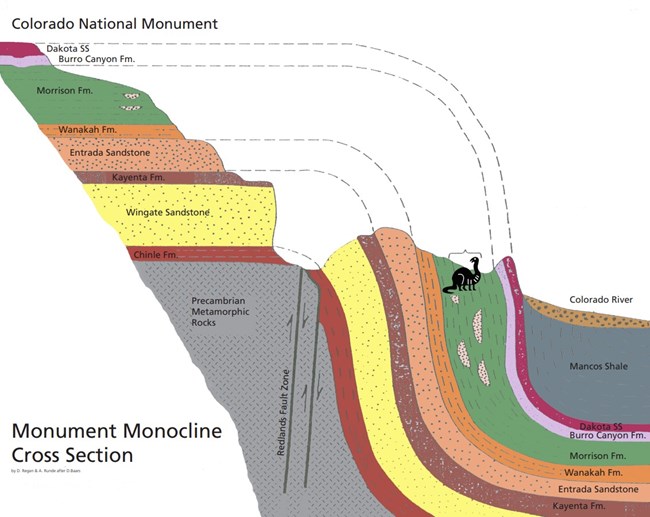

NPS Diagram Monocline: One SlopeA monocline forms the lazy S shape that connects rock layers from the valley floor to the monument cliffs. The idea of uplift is relative to the local area, meaning that the upper section is only considered "up" relative to the lower section. It's possible that the lower section might have sunk, rather than the upper portion being elevated. In the zone where the rock layers moved in different directions (up and down), some bent, some broke, and many have eroded. The generalized cross section to the left reveals how we can see the effects of this uplift in the rock layers within and outside the monument. Plateau within PlateauThe Uncompahgre Plateau was a highland long before the Colorado Plateau reached modern elevations. Erosion of this ancient highland fed sediments into adjacent basins that later became familiar rock layers elsewhere. This erosion also contributed to our local section of the Great Unconformity, the "missing" rock layers between the Precambrian rock and the Chinle layer at the monument. As the Colorado Plateau uplifted in stages, old faults were reactivated, and the Uncompahgre Plateau was tilted and lifted even more. Recent deep‑Earth processes plus river incision have accentuated that height difference. Changes in the lithosphere have raised elevations along plateau margins. Also, as rivers slowly remove rock, the crust rebounds slightly ("isostasy"), accentuating height differences over millions of years. One Piece of the Grand ValleyThe diagram below reveals where the south (left) side of the Grand Valley was uplifted. The area at the edge of the movement where the rock layers broke is called a fault, nowadays called the Redlands Fault. Rock layers that make up the Book Cliffs on the north side of the Grand Valley also once stretched across the entire area. At one time, all these rock layers piled above the present-day monument. You can imagine extending the lines from the right side of the diagram to the left. All these layers were buried underground until erosion and the ancestral Colorado River began carving the Grand Valley.

NPS Diagram |

Last updated: January 20, 2026