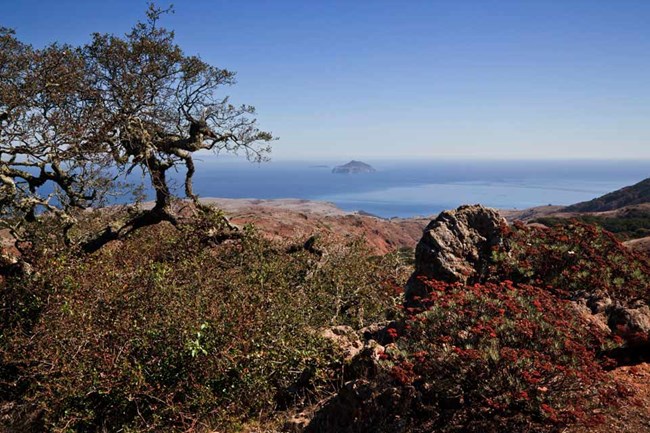

The chaparral found on the Channel Islands is known as island chaparral, and while it is similar to mainland chaparral, there are some differences. The dominant island chaparral species tend to be taller and more tree-like resulting in an open woodland appearance. This may be due in part to climatic differences, a lower fire frequency, or the effects of long-term, intensive grazing. Additionally, some of the species that characterize mainland chaparral communities, such as manzanita, are replaced in island chaparral by endemic species that are unique to the Channel Islands.

© Gary A. Monroe

Jessica Weinberg McClosky / NPS.

Minette Layne |

Last updated: June 17, 2016