NPS/WACC 86-16-0850 The stones that compose the Garfield Fireplace are the most tangible connection to the Buffalo Soldiers stationed in Bonita Canyon. Originally part of a three-tiered monument, today the hand-carved stones show visitors a bit of soldiers’ personalities. Some stones have names written in beautiful script, others are perfect block print, as if they were typed, and not carved by hand. A few men embellished their stones with crossed cavalry sabers, their troop letter, or dates. Men in Troops E and H of the 10th Cavalry dedicated this monument to President James Abram Garfield, who was assassinated in 1881.

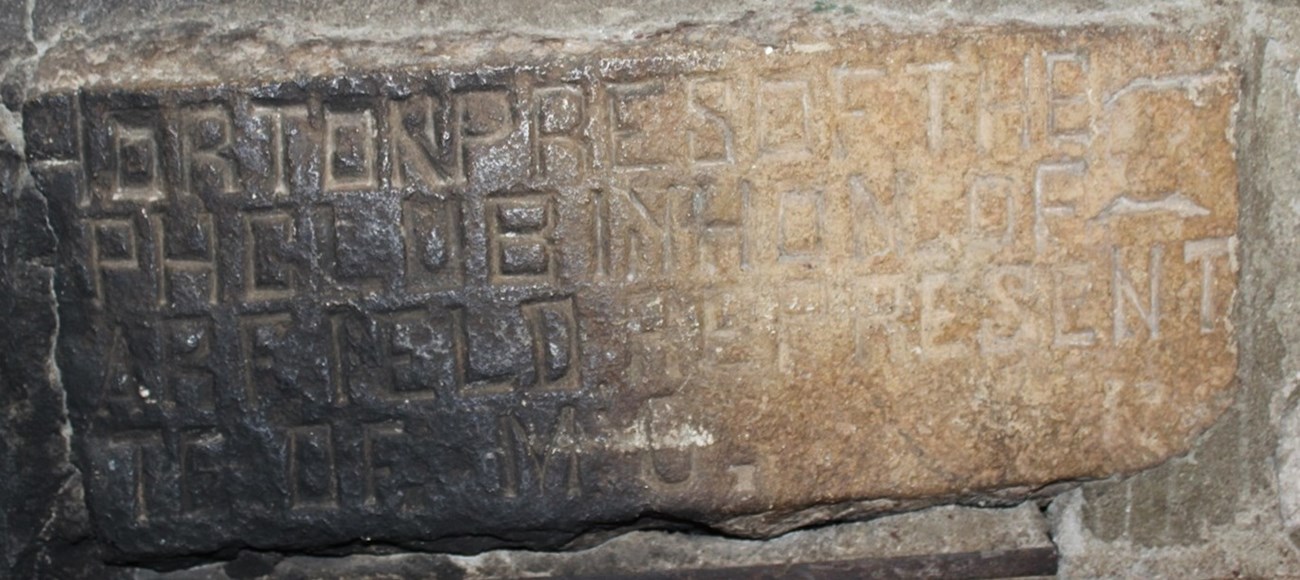

Some of the blocks in the fireplace are clearly carved by specific soldiers, while others are broken, obscuring what was once engraved in stone. George Horton, saddler for Troop H, might have had the original idea for the monument, although whose idea it actually was is lost to history. Horton’s block is broken, but it might have read: “(GEORGE H)ORTON, PRESIDENT OF THE (TROO)P H CLUB IN HONOR OF (JAS. A. G)ARFIELD, PRESPRESENTING (THE STA)TE OF MISSOURI.” Researchers speculate that the “H” might stand for Heliograph, but heliographs were not in widespread use until the end of the Geronimo Campaign. “H” might also simply be the letter of the troop.

NPS President Garfield is not often remembered, but in 1886, his 1881 assassination would have been recent history to the soldiers. During the Civil War, General Garfield commanded black volunteers from Ohio (the 42nd Ohio Regiment of Volunteers), and after the Civil War, Garfield was a Congressman who advocated for black rights during the Reconstruction Era in the South. No one knows why the soldiers chose President Garfield, but researchers surmise that his role as a military general and advocate for black rights might be the reason.

When Neil and his wife Emma moved to Bonita Canyon in 1888, the soldiers had only left two years before. Neil and Emma probably saw the Garfield Monument in its glory. Neil wrote to a number of people in Washington, D.C., related to President Garfield, as well as commanders in the 10th Cavalry, but none of them was interested in saving this little monument in southeast Arizona. The monument built by Buffalo Soldiers was left to weather away, and as years went by, people took stones from the crumbling monument as souvenirs.

Only a few photos of the monument exist, and these show a disintegrating stone structure. Fortunately, Lillian and Ed Riggs had the foresight to save the monument by dismantling it and preserving it in the form of a fireplace. Neil Erickson, Lillian’s father and an early Swedish pioneer in Bonita Canyon, was at first reluctant to let his daughter and son-in-law dismantle the monument.

Lillian and Ed finally received Neil’s permission to disassemble the stone monument and reassemble it as a fireplace, the centerpiece of their new guest dining room, in 1920. Sixty engraved stones are included in the fireplace.

NPS/WACC Prompted by a letter written in 1893, the US Army looked into the monument, but mistakenly identified it as a camp bake oven. In 1966, Lillian recollected: “The monument with all the tiers intact and every stone in place stood about five hundred yards from my home and as school children we played a lot around it. For that reason I have a very clear memory of what it was like before it began to deteriorate. … The man who engineered this structure surely knew his business. Each stone was smooth-faced and regular in shape though not all were the same size or dimensions. … The whole structure was put together with adobe mud, although it seems that some other building material must have been used as the top sides of the different tiers were smooth and waterproof. The joining of the stones was well seamed as if cement were used…”

More than 130 years after the Buffalo Soldiers built the Garfield Monument, and almost 100 years after Lillian and Ed Riggs converted the stones into a fireplace at Faraway Ranch, visitors to Chiricahua National Monument today can still connect to the Buffalo Soldiers.

National Archives, 2668824. The Henry Flipper ConnectionWhile Henry Ossian Flipper was not stationed at Bonita Canyon, someone carved his name perfectly into stone. Perhaps Flipper encountered men from Troops E, H, or I out on patrol in 1885 or 1886 while he was surveying land in southern Arizona. By the time the 10th Cavalry troopers were assigned to Bonita Canyon, Flipper’s military career had been cut short when he was accused of embezzling money and dishonorable conduct at Fort Davis, Texas in 1881. Many of the soldiers later stationed in Bonita Canyon were also briefly stationed at Fort Davis and may have met Flipper there.

It is unlikely that Flipper ever visited the temporary camp in Bonita Canyon, but someone meticulously carved Flipper’s name into one of the stones that comprised first the Garfield Monument, and then the Garfield Fireplace at Faraway Ranch. After Flipper’s dishonorable discharge, he continued his life in the southwest, working as a land surveyor, as a Spanish translator for the US Department of Justice, and eventually as a mining engineer in Mexico and Venezuela. Even if none of the soldiers personally knew Flipper, as the first black graduate from West Point Military Academy in 1877, he would have been a great role model for the men, as well as for their children, to aspire to become a commanding officer in the US Army.

NPS Flipper always proclaimed his innocence, and in 1976 the Army Board for Corrections of Military Records re-examined Flipper’s court-martial and decided it was unjustly harsh. In 1999 President Bill Clinton issued a posthumous pardon to the Second Lieutenant, who had died in 1940, at the age of 84. Soldiers Stationed at Bonita Canyon |

Last updated: August 19, 2018