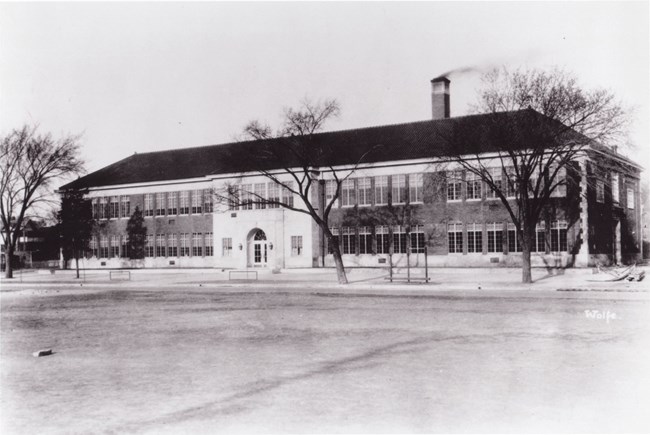

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka was the culmination of a plan by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to integrate public schools in the United States as part of their larger mission to achieve equity, political rights, and social inclusion for all people of color. The case resulted in a decision on May 17, 1954, by the U.S. Supreme Court to eliminate segregation in public schools, as highlighted by this excerpt from the opinion written by Chief Justice Earl Warren. “We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” However, this decision faced intense resistance and lack of enforcement. After a year of deliberating, the U.S. Supreme court issued the resolution to the Brown decision, often referred to as Brown II, on May 31, 1955, instructing segregated states to begin integrating their schools ‘with all deliberate speed.’ Background Racial discrimination in the Americas is much older than the United States. Even institutionalized racial slavery began as early as 1619 in Point Comfort Virginia with the first document slave ship carrying human beings as cargo for sale. Slavery persisted in the United States until December 6, 1865, with the ratification of the 13th amendment. Even this allowed for slavery as punishment for a crime. White supremacists in the United States who had supported slavery began to put ‘Black Codes’ in place, which set different and discriminatory laws for people of color, but not whites. The Black Codes lasted until July 9, 1868, with the passing of the 14th amendment guaranteeing “equal protection of the law.” Instead of being removed, however the Black Codes evolved into Jim Crow: laws which pass as fair and equal on paper, but in practice are discriminatory. Laws such as literacy tests to vote were meant to make it more difficult for former enslaved people to vote, as it was illegal to teach them to read during enslavement. We also begin to see segregation laws cropping up across the country. Kansas, despite being a free state, allowed for segregation of elementary schools in cities with populations of 15,000 or more as early as 1879. Parents began to challenge these laws as early as 1881. By 1950, 11 court challenges to segregated schools had reached the Kansas State Supreme Court. Unfortunately, none of them were successful. The NAACP was also facing its own share of difficulties trying to integrate public schools. Their initial plan was to focus on areas where there were few Black opportunities compared to whites, and physical conditions themselves were discriminatory. What they were met with, despite winning several cases, were rulings to ‘equalize’ the schools in question. Equalization was a way to allow school board to throw a little bit of money at the inferior schools they had built for children of color and hope the lawsuits would go away. Brown: The Community Lucinda Todd was a teacher turned activist, whose pursuit of equal education for her daughter led her to become one of the primary voices challenging segregation in Topeka. Todd had been forced to give up her career as a teacher when she started a family in 1935. She began working for the Topeka Chapter of the NAACP as its secretary in 1948, focused on challenging discrimination she saw in her city. For example, newspapers in Topeka advertised a concert by all “18 Topeka elementary schools,” and an instrument loan program that made the concert possible. Todd was dismayed as there were 22 schools in Topeka. The program and concert had excluded the four all-black schools in the city. Black students were banned from school dances, forced onto separate sports teams and numerous other forms of segregation and discrimination in Topeka. Todd offered her home as a headquarters for the Citizens Committee on Civil Rights rallying community members, working with the NAACP, and even leading drives and petitions such as “The People Fight Back,” obtaining 1,100 signatures opposing segregation in Topeka schools that unfortunately fell on deaf ears from the school board. It was Todd who suggested the idea of a legal challenge in Topeka to Walter White, executive secretary for the NAACP, and Charles Bledsoe, an attorney for the Topeka Chapter of the NAACP. Bledsoe reached out to Robert L. Carter with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund who began to strategize a legal approach. Carter recommended recruiting as many parents as possible to enroll their children in local white schools so when they were denied they could provide the NAACP the documentation they’d need to file a lawsuit. Todd and the local NAACP chapter recruited 13 families, starting with her own, who would participate in the lawsuit. Nancy Todd, Lucinda’s daughter, was forced to ride a bus to an all-black elementary school, despite having an all-white neighborhood school just a few blocks from her home. Nancy Todd wasn’t alone in her experience, as most of the students of the families recruited by the NAACP also had to pass white schools as they traveled several blocks further to attend an all-black school. Brown: The Case The Topeka NAACP filed suit on behalf of the families in February of 1951, but by August, the U.S. District Court ruled that, although segregation might be detrimental, it was not illegal. Citing the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the judges denied relief on the grounds that the black and white schools in Topeka were equal with respect to buildings, transportation, curricular, and educational qualifications of teachers. The plaintiffs appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1952 and were joined by four similar NAACP-sponsored cases from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington, D.C. The court ruling combined these five cases under the heading Oliver L. Brown et. al. vs. the Board of Education of Topeka, (KS) et. al. Mr. Brown was the assigned lead plaintiff in the Kansas class action suit and became namesake of the court decision. Chief Council for the NAACP Thurgood Marshall argued before court that separate school systems for blacks and whites were inherently unequal, and thus violated the "equal protection clause" of the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Marshall also argued that segregated school systems tended to make black children feel inferior to white children, and thus such a system should not be legally permissible. The Decision The Supreme Court Justices heard the case in the spring but were unable to decide the issue by the end of the court's term in June. The Justices decided to rehear the case in the fall with special attention paid to whether the 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause prohibited the operation of separate public schools based on race. In September Chief Justice Fred Vinson, who had been a key stumbling block to a unanimous decision, died and was replaced by Governor Earl Warren of California. Warren had supported the integration of Mexican American students in California school systems in 1947, after Mendez v. Westminster and when Brown v. Board of Education was reheard, Warren was able to bring the Justices to a unanimous decision. On May 14, 1954, Chief Justice Warren delivered the opinion of the Court, stating: "Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn … … We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment." The decision in Brown v. Board of Education forced the desegregation of public schools in 21 states and intensified resistance in the South, particularly among white supremacist groups and government officials sympathetic to the segregationist cause. In Virginia, U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd, Sr. started the Massive Resistance movement, which sought to pass new state laws and policies as a means of keeping public schools from being desegregated. In one of the most notorious instances of resistance to the decision, Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus called out the National Guard in 1957 to keep black students from entering Little Rock Central High School. For African Americans, the Supreme Court's decision encouraged and empowered many who felt for the first time in more than half a century that they had a "friend" in the Court. The strategy of education, lobbying, and litigation that had defined the Civil Rights Movement up to that point broadened to include an emphasis on a "direct action." This included boycotts, sit-ins, Freedom Rides, marches, and other tactics that relied on mass mobilization, nonviolent resistance, and civil disobedience all of which would come to define the Modern Civil Rights Movement. Citations: Kluger, Richard. 2004. Simple justice: The History of Brown V. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality. Vintage. “Lucinda Todd.” Kansas Historical Society, May 1, 2011. https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/lucinda-todd/16897. Brown Foundation. 2019. “Brown Case - Brown v. Board | Brown Foundation.” Brownvboard.org. 2019. https://brownvboard.org/content/brown-case-brown-v-board. African American Experience FundThe mission of the African American Experience Fund of the National Park Foundation is to preserve African American history by supporting education programs in National Parks that celebrate African American history and culture. There are 26 National Parks identified by the African American Experience Fund: |

Last updated: March 5, 2026