Last updated: May 12, 2023

Article

The Mary McLeod Bethune Council House: African American Women Unite for Change (Teaching with Historic Places)

This lesson is part of the National Park Service’s Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) program.

The soft velvet rug that carpets the staircase that leads to the office of the president has felt the tread of many feet—famous feet and humble feet; the feet of eager workers and the feet of those in need; and tired feet, like my own, these days. I walk through our headquarters, beautifully furnished by friends who caught our vision, free from debt! I walk through the lovely reception room where the great crystal chandelier reflects the colors of the international flags massed behind it—the flags of the world! I go into the paneled library with its conference table, around which so many great minds have met to work at the problems of the past years. I feel a sense of peace. Women united around The National Council of Negro Women, have made purposeful strides in the march toward democratic living. They have moved mountains. Our headquarters is symbolic of the direction of their going, and of the quality of their leadership in the world of today and tomorrow.1

Mary McLeod Bethune wrote these moving words upon her retirement as president of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) in 1949. Bethune had founded the organization in 1935 to give African American women a collective national voice at a time when they were typically shunned or ignored. As NCNW grew and gained respect, Bethune spearheaded the effort to establish a national headquarters in Washington, D.C. When a red brick townhouse in the Logan Circle area became available, Bethune quickly moved to purchase it. As the first headquarters of the National Council of Negro Women, this house played a prominent role in advancing the causes of African American women around the country. From 1943 until 1966, it provided the setting for countless meetings in which NCNW members discussed pivotal national events such as the integration of the military and public schools. Here also they created and implemented programs to combat discrimination in housing, healthcare, and employment.

Bethune and the members of NCNW faced challenges of race and gender with a tireless spirit and determination. Bethune helped give a voice to African Americans and created an organization that continues to fulfill her vision more than 50 years after her death. Today the former headquarters is administered by the National Park Service as the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site.

1As quoted in Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999), 193.

About This Lesson

As a historic unit of the National Park Service, the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The site also is within the boundaries of the Logan Circle Historic District. This lesson is based on the Historic Resources Study for Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site, as well as other materials on Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women. The lesson was written by Brenda K. Olio, former Teaching with Historic Places historian, and edited by staff of the Teaching with Historic Places program and Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history, social studies, government, civics, and geography courses in units on the Civil Rights Movement, African American history, women's history, the New Deal, and political activism.

Time period: Early to mid 20th century

|

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12The Mary McLeod Bethune Council House: African American Women Unite for Change relates to the following National History Standards:

Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies(National Council for the Social Studies)

The Mary McLeod Bethune Council House: African American Women Unite for Change relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme II: Time, Continuity, and Change

Theme III: People, Places, and Environments

Theme IV: Individual Development and Identity

Theme V: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions

Theme VI: Power, Authority, and Governance

Theme IX: Global Connections

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

Objectives for students1) To explain the status of African American women in the first half of the 20th century Materials for studentsThe materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The maps and images appear twice: in a smaller version with associated questions and alone in a larger version. Visiting the siteMary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site is located at 1318 Vermont Avenue NW, Washington, D.C. 20005. The site is open Monday through Saturday from 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. except Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year's Day. The National Archives for Black Women's History is open by appointment only. For more information, visit the park's website. The Council House also is within the boundaries of the Logan Circle Historic District. This district is bounded roughly by Q Street on the north, N Street on the south, 11th Street on the east, and 14th Street on the west. For more information, visit the Logan Circle Community Association's website. |

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

When might this photo have been taken? What appears to be taking place in the photo?

Setting the Stage

In the years following the Civil War, newly-freed slaves made many political and economic advances as the U.S. government created policies intended to reunite the country while punishing Southerners for seceding. By 1877, however, the period known as Reconstruction had ended and Southerners once again gained political control in their states. Determined to keep African Americans from fully participating in mainstream American life, Southern leaders passed state and local laws that required racial segregation.

In 1896, the Supreme Court's Plessy v. Ferguson ruling declared that racial segregation was constitutional as long as the facilities for blacks and whites were equal. In reality, facilities for African Americans were seldom equal to those reserved for whites. Schools for African American children in southern communities, for example, were either nonexistent or substandard. As a result, most African Americans struggled to obtain a basic education. Without sufficient opportunities to attend school, these children did not have a fair chance to improve their situations.

African American women had even fewer opportunities because they faced both gender and race discrimination. In the early 20th century, women's groups were continuing to fight for the right to vote, but these groups often denied membership to African American women. While white women who worked outside the home generally held clerical or sales jobs, the vast majority of African American women worked as farm laborers or domestic servants. As one historian claimed, African American women were "so hampered by the multiple burdens of gender, race, and class that of all groups in the nation, they have been on the farthest fringes of opportunity, economic security, and civic participation."1 Out of this oppressive climate, Mary McLeod Bethune rose to international prominence as a political activist.

The child of former slaves, Bethune was fortunate enough to receive an education. Wanting to give other children of her race the same opportunity, she opened a school for African American girls in 1904. From very humble beginnings, this small school in Florida eventually grew into a fully accredited, co-educational university. Bethune's continued determination to improve the lives of all African Americans, and African American women in particular, led her to become active in several women's clubs as well as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

n 1935, she founded the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) to give African American women a means to be heard on the national level. In 1943, Bethune and the NCNW purchased a townhouse in Washington, D.C. to serve as a headquarters. From this building, NCNW coordinated national efforts to end discrimination and improve education, healthcare, and job opportunities for African Americans. Today, the site is administered by the National Park Service and is known as the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site.'

1Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999), 131.

Locating the Site

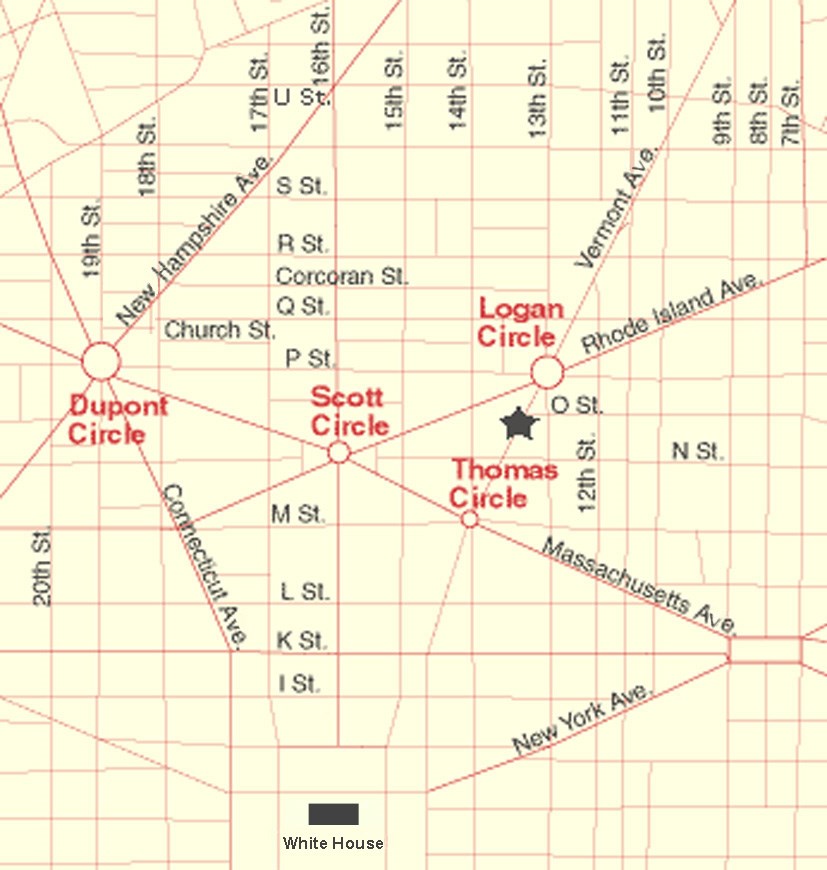

Map 1: Logan Circle and surrounding area, Washington, D.C.

(Courtesy of WETA)

Map 1 shows the location of Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site (denoted by star). At the time of its construction in the mid 1870s, the townhouse that later became the first headquarters of the National Council of Negro Women was situated in a fashionable residential D.C. neighborhood. By the latter part of the 19th century, this area—eventually known as Logan Circle in honor of Civil War Union General John Logan—had become a popular neighborhood for white upper middle-class businessmen and politicians as the capital city grew. At the end of the century, however, these wealthy homeowners began to relocate toward nearby Dupont Circle.

At the same time, more and more African Americans began moving into the Logan Circle area and other neighborhoods to the north, particularly along U Street between 7th and 16th Streets. By 1920, this entire area had become the center of African American life in the segregated capital city. The U Street corridor featured a large number of businesses and entertainment facilities owned by African Americans, and the surrounding neighborhoods became home to many of the city's most prominent black citizens. When Bethune purchased the Vermont Avenue house in 1943 on behalf of NCNW, neighbors included African American attorneys, ministers, and a doctor.

Questions for Map 1

1. Using a classroom map of the United States, locate Washington, D.C. Next, identify the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site on Map 1. How would you describe its location?

2. Locate the U Street corridor and describe its character in the first half of the 20th century. How many blocks away from Logan Circle is U Street?

3. How did the makeup of the Logan Circle area change over time? Why might this neighborhood have appealed to Bethune and NCNW in the 1940s?

4. Note the location of the house in relation to the White House. How might this have benefited an organization such as NCNW?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Mary McLeod Bethune

Humble Beginnings

Mary McLeod was born on July 10, 1875, near Mayesville, South Carolina. She was the fifteenth of 17 children born to former slaves Samuel and Patsy McLeod. Racism was prevalent in the post-Reconstruction South. At this time, African American children did not have many opportunities to attend school. Mayesville did not have a school for blacks until Emma Wilson, an African American teacher and missionary, founded the Trinity Presbyterian Mission School in 1882.

In 1885, Mary became the first member of her family to attend the new school. For the next several years, she walked five miles to the one-room school. Impressed by Mary's determination, Wilson chose her as the recipient of a scholarship to attend Scotia Seminary, a school for black women in North Carolina. The scholarship was provided by a teacher in Colorado who wanted to help an African American girl further her education.

After McLeod graduated in 1894, her benefactor paid for her to attend the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago. When she completed the program the following year, McLeod was anxious to serve as a missionary in Africa. She was told by the Presbyterian Mission Board, however, that there were no missionary positions available for blacks in Africa. Although disappointed, McLeod soon acknowledged that "Africans in America needed Christ and school just as much as Negroes in Africa….My life work lay not in Africa but in my own country."1 She returned to Mayesville, South Carolina, and began teaching at her former school.

Soon she moved to Augusta, Georgia, to teach at Haines Normal and Industrial Institute. There she worked with Lucy Laney, founder and principal of the school. Laney's dedication to serving others inspired McLeod. In May 1898, she married Albertus Bethune, a clothes salesman, and moved to Savannah, Georgia. The couple had a son in February 1899 and shortly thereafter moved to Palatka, Florida, where Mrs. Bethune opened a mission school for poor African American children.

In 1904, the family moved to Daytona Beach, Florida, so Mrs. Bethune could open a school for the children of poor black laborers on the Florida East Coast Railroad. She found a rundown building and persuaded the owner to accept $1.50 as a down payment for the $11 per month rent. She rummaged for discarded supplies and found a barrel to use as a desk and crates for chairs. Of that time, she later wrote, "I haunted the city dump and the trash piles behind hotels, retrieving discarded linen and kitchen ware, cracked dishes, broken chairs, pieces of old lumber. Everything was scoured and mended."2 In October 1904, the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls opened with five students (ages 8-12) who paid 50 cents a week for tuition.

By 1906, the school had almost 250 students. Needing a bigger space, Bethune set out to raise money by selling homemade ice cream and sweet potato pies and putting on concerts. She even rang doorbells asking for donations. Bethune later remembered, "If a prospect refused to make a contribution, I would say, 'Thank you for your time.' No matter how deep my hurt, I always smiled. I refused to be discouraged, for neither God nor man can use a discouraged person."3 Finally, with the help of a few wealthy businessmen, Bethune was able to purchase land and build a brick school.

Bethune believed that in order to advance, African Americans must first achieve financial independence. To do this, they must learn manual skills that would help them earn jobs. As a result, students studied sewing, cooking, broom making, weaving, housekeeping, etc., as well as academic subjects and religion. This educational philosophy was advanced by Booker T. Washington, a respected black leader who founded the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Bethune admired Washington and even had the privilege of receiving him as a visitor to her school. In 1908, Bethune's husband decided to return to South Carolina, leaving her and her son on their own. By 1916, the school offered a high school curriculum with training in nursing, teaching, and business.

Despite Bethune's relentless fundraising efforts, the school continued to struggle financially. In 1923, it merged with a college in Jacksonville, Florida, and became Bethune-Cookman College with almost 800 students. Bethune remained president of the school until 1942, when she resigned in order to focus on her national agenda.

Growing Recognition

Mary McLeod Bethune's work as an educator ultimately led her to become an influential political activist. In 1909, she attended a conference of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs (NACWC). The passionate speech she gave about her Florida school inspired the attendees to take up a collection. NACWC's president, Mary Church Terrell, was so impressed that she predicted Bethune would one day become president of NACWC.

In the years that followed, Bethune assumed leadership positions in several African American women's clubs. In 1924, Bethune fulfilled Terrell's prediction by serving as president of the NACWC, the highest national position for a black woman at that time. As NACWC president, she led the organization to focus on social issues facing all women and society in general. The group lobbied for a federal antilynching bill and prison reform and offered job training for women.

Through her participation in national women's groups, Bethune made many contacts and formed important friendships.

As a member of the National Council of Women of the United States, she attended a luncheon hosted by Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt's wife in New York. Bethune, the only African American woman at the event, soon began a close friendship with Mrs. Roosevelt. In 1928, Bethune was the only African American invited to take part in a conference on child welfare in Washington, D.C. In 1929, President Hoover asked her to serve on the National Commission for Child Welfare and the Commission on Home Building and Home Ownership.

In both roles, she advised the government on the needs of African Americans.

Bethune's influence continued to increase in the 1930s as the nation was plunged into the Great Depression. Her relationship with Eleanor Roosevelt proved even more important once Franklin Roosevelt became President of the United States. The "New Deal" that FDR promised Americans resulted in many programs designed to provide financial relief. Among these was the National Youth Administration (NYA), created in 1935 to ease unemployment among Americans ages 16 to 25. When First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt invited Bethune to join the NYA Advisory Committee, Bethune accepted the volunteer position and even moved to Washington, D.C. The NYA focused on education, job training, and employment.

Young African Americans often suffered even more than whites because of the economic condition of their families prior to the Depression. Added to this was the fact that many white people, desperate for work, were taking over jobs in agriculture and domestic work previously held by blacks. To help combat these issues, Bethune encouraged black participation and leadership in NYA programs.

National Influence

Impressed by Bethune's work, FDR offered to put her in charge of a new department within NYA—the Division of Negro Affairs. Aubrey Williams, administrator of the NYA, encouraged her to accept, saying, "Do you realize that this is the first time in the history of America that an administrative government office has been created for one of the Negro race?"4 On June 24, 1936, Bethune officially joined the NYA Washington staff as director of the Division of Negro Affairs. As such, she became the first black woman to head a department of a federal agency.The NYA position earned Bethune recognition and prestige. A group of newspapers named her one of the 50 most influential women in America and the NAACP awarded her their prestigious Spingarn medal for outstanding achievement by a black American. Eleanor Roosevelt stated, "She had a great deal of influence with the President, who had complete trust in whatever she told him as it affected the young people of her race while she was working in the NYA."5

In 1936, as part of her effort to focus attention on racial inequality, she organized the Federal Council on Negro Affairs, which became known as the Black Cabinet. Comprised of African Americans who had been appointed to various government agencies, the group first met in August 1936 at Bethune's apartment. They focused on how blacks could be better represented in the administration and how they could best benefit from New Deal programs. Bethune explained, "We have had a chance to look down the stream of the forty-eight states and evaluate the type of work and positions secured by Negroes. The responsibility rests on us. We can get better results by thinking together and planning together….Let us band together and work together as one big brotherhood and give momentum to the great ball that is starting to roll for Negroes."6

Although the Black Cabinet did not operate in an official capacity, the group made studies and submitted reports to the federal government over the course of seven years. Within six months of being in Washington, Bethune had "managed to bring together for unified thought and action all of the colored people high in government authority."7 By the mid 1930s, Bethune's tireless energy and devotion had secured her reputation as a powerful figure in the fight for African American and women's rights.

Questions for Reading 1

1. How was Mary McLeod able to attend Scotia and Moody Bible Institute? How do you think this generous gift impacted her life and her desire to help others?

2. Who were some of the people who influenced Bethune?

3. Based on the reading, what were some of the character traits that helped Bethune succeed? What specific examples of these traits can you find in the reading?

4. How did Bethune go from being an educator to a political activist?

5. What was the NYA? What was Bethune's role? How did this role help her gain recognition?

6. What were some of the tactics Bethune used to achieve her goals (both for her school and her national agenda)?

7. What was the Black Cabinet? Why was it important?

Reading 1 was adapted from Andrea Broadwater, Mary McLeod Bethune: Educator and Activist (Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers, Inc., 2003); Malu Halasa, Mary McLeod Bethune: Educator (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1989); Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999); Elaine M. Smith, Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women: Historic Resource Study (Alabama State University, 2003); and Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: General Management Plan (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2001).

1Malu Halasa,, Mary McLeod Bethune: Educator (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1989), 34.

2Andrea Broadwater, Mary McLeod Bethune: Educator and Activist (Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers, Inc., 2003), 37.

3Ibid., 52.

4Elaine M. Smith, Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women: Historic Resource Study (Alabama State University, 2003), 73.

5Ibid., 104.

6As quoted in McCluskey and Smith, eds., 227.

7Smith, 103.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: The National Council of Negro Women

The Early Years

By the mid 1930s, Mary McLeod Bethune was recognized as a leader in the fight for African American rights. One of her goals, however, remained unfulfilled. As early as 1928, Bethune had raised the notion of forming a coalition of black women's organizations. By this time, she felt that the NACWC did not focus enough on national issues relating to African American women. She strongly believed that if black women presented a united front, they could become a powerful force for promoting political and social change.

Many separate organizations and individuals could not hope to accomplish as much as an "organization of organizations." In March 1930, Bethune held a meeting to officially propose her idea. The women present decided to set up a committee for further study rather than immediately initiate such a group. Bethune was disappointed, but did not give up. Five years later, on December 5, 1935, she addressed another group:

Most people think that I am a dreamer. Through dreams many things have come true. I am interested in women and believe in their possibilities. The world has not been willing to accept the contributions that women have made. Their influence has been felt more definitely in the past ten years than ever before. We need vision for larger things, for the unfolding and reviewing of worth while things….We need an organization to open new doors for our young women and when the council speaks its power will be felt.1

This time the group—representatives of 29 diverse black women's organizations—agreed to establish the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). With Bethune as its president, this new organization would hopefully provide a strong national voice on issues such as education, employment, health, and civil rights. A group such as this would yield more influence and thus make greater advances. She wrote, "The great need for uniting the effort of our women kept weighing upon my mind. I could not free myself from the sense of loss, of wasted strength, sustained by the national community through failure to harness the great power of women into a force for constructive action. I could not rest until our women had met this challenge."2

NCNW incorporated in Washington, D.C. on July 25, 1936. According to the organization's constitution, the four major objectives were:

-

1. To unite member organizations into a National Council of Negro Women.

2. To educate and encourage Negro women to participate in civic, political, and economic activities in the same manner as all other Americans participate.

3. To serve as a clearing house for the dissemination of information concerning activities of organized colored women.

4. To initiate and promote, subject to the approval of member organizations, projects for the benefit of the Negro.

As Bethune explained:

The paramount objective of the Council is to bring together the representatives of all types of national organizations among Negro women—church and fraternal, business and professional, federated clubs, sororities, etc.—representing youth and maturity, in order to pool the best thinking of the entire group for concerted action upon the problems pertinent to the race, the nation and the world. The Council seeks further to integrate the thoughts and ideals of the Negro womanhood of our nation into the planning and thinking of the women of other races in America and the World.3

During its first year, NCNW limited membership to national women's organizations and individual life members. Soon, however, local NCNW chapters known as Metropolitan Councils were established. A Board of Directors administered the Council and volunteer executive secretaries ran the national office out of Bethune's D.C. apartment. Thirteen NCNW committees began addressing issues such as employment, education, franchisement (voting), and lynching. One area of concern to NCNW was the lack of federal government jobs available to black females. When Bethune wanted to conduct a conference on this issue she had "to go to Mrs. Roosevelt about two months ahead and sit and talk with her for an hour on the importance of this so as to bring it there under government surroundings and shrouded in governmental setting to give prestige and history to it."4

On April 4, 1938, about 65 African Americans took part in this historic conference at the White House. Although the group's recommendations remained unfulfilled six months later, Bethune continued to be optimistic. She explained to NCNW members, "The pressure we have been making, the intercessions that we are making, they are finding their way. A door has been sealed up for two hundred years. You can't open it overnight but little crevices are coming, little leakages are getting through."5

NCNW continually strived to be included in organizations and activities that discussed important national topics. Bethune contended, "Wherever women are working for good citizenship, social and economic welfare, community health, nutrition, child welfare, civil liberties, civilian defense and other projects for the advancement of the people—there also we must be…."6 Not surprisingly, when NCNW was excluded from a conference of the Women's Interest Section in the War Department in 1941, Bethune protested:

We are anxious for you to know that we want to be and insist upon being considered a part of our American democracy, not something apart from it. We know from experience that our interests are too often neglected, ignored or scuttled unless we have effective representation in the formative stages of these projects and proposals….We are incensed!7

The Army reconsidered and invited NCNW to become a member of the Women's Interest Section. This important victory helped NCNW become the nationally recognized representative of African American women as the country entered World War II.Throughout the war, NCNW found ways to express patriotism. In July 1943, it initiated an annual "We Serve America Week" to "demonstrate to all America the contributions made by Negro women to our war effort and to the support of our democratic ideals."8 Activities in Washington, D.C. included a parade, speeches, and a party. The highlight of the festivities the following year was the launching of a U.S. merchant marine Liberty Ship dubbed the S.S. Harriet Tubman. NCNW had sponsored the construction of the ship through the sale of war bonds. Built to transport supplies to troops overseas, this ship was the first to honor an African American woman.

NCNW tried also to focus on international relationships. During the spring of 1945, 50 nations gathered in California to formally create the United Nations. Through perseverance, Bethune earned the honor of being an associate consultant to the American delegation at that meeting. NCNW was not an official consultant, but Bethune used the opportunity to promote her organization. She said, "I regard it as the greatest opportunity of my life to lend my strength and spiritual power to the building of a new and better one-world."9

Establishing a Headquarters

Bethune had always wanted NCNW to have an official headquarters instead of using her rented apartment to conduct business. In 1943, Bethune set her sights on a three-story townhouse for sale for $15,500 in Washington. With the help of a few friends, she secured $500 for the down payment. Wealthy Chicago businessman Marshall Field donated $10,000 towards the house. NCNW officials granted Bethune the right to live in the house for free. Members worked hard to update the building and secure furnishings from friends and other organizations.

Finally, during the annual meeting in October 1944, NCNW members held a special ceremony to dedicate the house. At the dedication, Bethune said, "Here women of all nationalities can come together without fear or hesitancy, secure in the knowledge that they meet as equals and as workers striving together."10 The headquarters provided a place to host social functions as well as conduct NCNW business. Dignitaries such as the Ambassador of Haiti and other distinguished guests from around the country and around the world visited the site. Although Bethune took great pride in the national headquarters, she had hoped that NCNW could acquire a larger space. This dream remained unfulfilled when the 74-year-old Bethune decided to step down as president in 1949.

Questions for Reading 2

1. Why did Bethune found NCNW? What were its major goals?

2. How did Bethune's friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt help her to pursue her causes?

3. What were some of the important issues that NCNW members worked to address? What are some examples of successes achieved by NCNW during Bethune's tenure as president?

4. Why do you think it was important for NCNW to have an official headquarters? How did the organization obtain the building?

Reading 2 was adapted from Dr. Bettye Collier-Thomas, NCNW: 1935-1980 (Washington, D.C.: The National Council of Negro Women, 1981); Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999); Elaine M. Smith, Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women: Historic Resource Study (Alabama State University, 2003); R. Brian Wright, The Idealistic Realist: Mary McLeod Bethune, The National Council of Negro Women and The National Youth Administration (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Master's Thesis, 1999); and Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: General Management Plan (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2001).

1As quoted in McCluskey and Smith, eds., 171.

2 Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site: General Management Plan (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 2001), 59.

3R. Brian Wright, The Idealistic Realist: Mary McLeod Bethune, The National Council of Negro Women and The National Youth Administration (Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Master's Thesis, 1999), 22.

4 As quoted in McCluskey and Smith, eds., 48.

5Smith, 54.

6 Ibid., 158.

7 As quoted in McCluskey and Smith, 174.

8Smith, 178.

9Ibid., 241.

10Ibid., 224.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: "Stepping Aside. . . at Seventy-four"

Mary McLeod Bethune wrote the following article for the October 1949 issue of Women United, a periodical of the National Council of Negro Women.

Women United goes to press as I make ready to turn over the president's desk at our national headquarters in Washington, to younger, stronger, surer hands, and I find, constantly through my mind, the faces of the women who have helped to make the foundation-laying of the National Council of Negro Women, during the past fifteen years, a work of joy.

I want to pay tribute to them! There are so many of these women, old and young. Fine, strong, alert women, clear-headed, far-seeing leaders in many fields. How much they have meant to me! There was no idea so big they could not grasp and develop it. No task so humble that they scorned it.

How they came around me and worked early and late, on problems which affected their individual lives [and] the lives of all women. They sought and found ways to integrate women into jobs; they joined forces to help push through legislation designed to lighten the burden of women and children; and in the far-flung areas trained and encouraged women to use the franchise to their advantage. These women worked at makeshift desks in the living room of my little apartment on Ninth Street, where my tired secretary would fall asleep, after the last volunteer had left with the dawn. And all this at the end of a hard day's work on important full-time jobs!...

Yes, this has been a work of joy—joy in the struggle and responsibilities which we sought and accepted. A means to the realization of a dream for the Negro women of America, united with their sisters of all races, throughout the world.

It was a dream of being able to say, "We will be heard!" It was a dream of hearing the voices of women united for progress, without regard for race, creed, color or political affiliation. Voices ringing out in place of authority to support the interests of the masses of our people, and of all forward-looking programs.

And, as I look down at my desk, piled high each day, with correspondence from all manner of people from all over the world…asking for the counsel and cooperation and leadership of the National Council of Negro Women, I know that one part of this dream at least, has been realized. This is the evidence, wage standards have been raised, social security broadened, government salaries increased. We are being heard!

The soft velvet rug that carpets the staircase that leads to the office of the president has felt the tread of many feet—famous feet and humble feet; the feet of eager workers and the feet of those in need; and tired feet, like my own, these days. I walk through our headquarters, beautifully furnished by friends who caught our vision, free from debt! I walk through the lovely reception room where the great crystal chandelier reflects the colors of the international flags massed behind it—the flags of the world! I go into the paneled library with its conference table, around which so many great minds have met to work at the problems of the past years. I feel a sense of peace.

Women united around The National Council of Negro Women, have made purposeful strides in the march toward democratic living. They have moved mountains. Our headquarters is symbolic of the direction of their going, and of the quality of their leadership in the world of today and tomorrow.

I have no fear for the future of women….May God bless all the women who have united with me in this effort, wherever they may be. They have the brains! May they have the moral power, and grant that He give them the spirit to carry on, to bulwark gains already made, to blaze new trails.

Questions for Reading 3

1. What seems to be the overall message Bethune is trying to convey in this article? What emotions or feelings do you think this article evoked in its readers? Which phrases or expressions do you think particularly inspired these emotions?

2. Bethune's reference to a dream is similar to that of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s famous speech years later. What was Bethune's dream? Did she think that any part of her dream had been realized by the time she wrote this article?

3. What do you think Bethune meant when she referred to the headquarters as "symbolic"? Do you agree that a building can represent something beyond a physical space? Explain your answer.

4. Why do you think it might have been important for Bethune to praise and encourage NCNW members upon her retirement?

Reading 3 was excerpted from Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds., Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999), 192-93.

Determining the Facts

Reading 4: The National Council of Negro Women: Beyond Bethune

When Bethune decided to step down as president of NCNW in 1949, she helped ensure that Dr. Dorothy Ferebee, her personal physician and NCNW's national treasurer, would be elected the next NCNW president. Not surprisingly, Ferebee put increased emphasis on healthcare education. Under her leadership, NCNW also focused on ending discrimination against blacks and women in the military, housing, employment, and voting. She continued fundraising efforts and participated in various meetings of national and international organizations. She was a member of the executive board of the White House's Children and Youth Council and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF).

In 1951, Ferebee led NCNW in hosting a reception for the wife of the Vice-President at the Shoreham Hotel in Washington, D.C. This event was important because it gathered approximately 500 women from diverse backgrounds. As a result of Ferebee's determination and leadership, it also was the first time that a major Washington, D.C. hotel had rented its main ballroom to an African American group. During her presidency, Ferebee also issued a "Nine Point Program" which called attention to the need to achieve "basic civil rights through education and legislation." She worked hard to advance NCNW's agenda while maintaining a full-time job at Howard University and dealing with limited funds and staff.

In November 1953, the Council elected Vivian Carter Mason as president. A graduate of the University of Chicago, Mason had been the first black female administrator in New York City's Department of Welfare. She was president of the Norfolk NCNW chapter and vice-president of the national organization under Dr. Ferebee. Mason's administrative skills were beneficial in helping to better organize NCNW headquarters and connect local chapters to the national office. Under her leadership, NCNW members participated in numerous meetings and conferences held by such groups as the U.N. Commission on the Status of Women, the American Association for the United Nations, the International Council of Women of the World, and the National Advisory Committee on Health. Mason served as president when NCNW marked its 20th anniversary in 1955. At a celebration in February, Mary McLeod Bethune praised the council members by saying, "I am very grateful to you, my daughters. I have been the dreamer. But, oh, how wonderfully you have interpreted my dreams."1 A few months later, Bethune died of a heart attack at her Daytona Beach home on May 18 at age 79.

During her lifetime, Bethune witnessed the tremendous growth of the organization she founded. Over its first 20 years, NCNW helped African American women break down barriers that often isolated them from mainstream America. Through perseverance, the council helped make it acceptable for black women to be a part of national and international affairs. Through increased interaction with white female organizations, NCNW tried to unite all women as equals and present a more accurate image of American black women to the world.

In 1957, Dorothy Irene Height, who had served for 20 years in various appointed positions with NCNW, became its fourth president. Height had the daunting task of leading NCNW during the early 1960s, a turbulent period of increased racial violence in the South as the Civil Rights Movement expanded. In 1963, she had offered NCNW headquarters as a meeting place for national organizations and individuals taking part in the March on Washington on August 28. During this period, civil rights advocates were being arrested in states such as Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. As tensions mounted, Height and NCNW launched a plan that called for racially mixed groups of women to visit rural communities in Mississippi each week during the summer of 1964 to foster better communication among the races and encourage voter registration among blacks. This highly successful project was known as "Wednesdays in Mississippi."

One of NCNW's consistent problems had been lack of funds, caused in part because the organization did not qualify for tax-exempt status. Without this designation, foundations and philanthropists were unlikely to donate large sums of money to NCNW because they had to pay taxes on their gift. Height made it a priority to revise the Articles of Incorporation and make other changes that resulted in the U.S. Internal Revenue Service granting tax-exempt status in 1966. That same year, sizeable grants from the Ford Foundation and the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare allowed NCNW to begin a "nationwide network of Negro women, working with all segments of their communities, middle-class and poor, Negro and white, to help chart and carry out needed community service and social action programs."2 Increased funding allowed the council to expand and standardize its programs on the national and local level.

While the council enjoyed a period of substantial growth in the mid-1960s, its headquarters suffered major water and smoke damage from a fire started by a leak in the heating oil tank in January 1966. As a result, NCNW had to move its headquarters to the Dupont Circle area. The building that had witnessed two decades of NCNW gatherings and had stood as a symbol to NCNW members remained vacant for several years. Finally, in 1975, grant money enabled NCNW members to begin restoring the townhouse for the purpose of reopening it as a museum. On November 11, 1979, the Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial Museum and National Archives for Black Women's History opened to the public. Decades earlier, Bethune recognized the need to preserve records related to African American history, particularly ones focusing on African American women.

NCNW's Library and Museum Committee had collected various materials through the years and showcased them in the Council House library. Occupying the carriage house behind the Council House, the archives today includes the records of NCNW, personal papers of African American women, records of other African American women's organizations, and a collection of more than 4000 photographs.

In October 1982, Congress designated the Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial Museum a National Historic Site. The National Park Service acquired it in 1994 and opened it to the the public as Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site on October 1, 1995. That same year, NCNW members proudly dedicated a new headquarters at 633 Pennsylvania Avenue, a prestigious address blocks from the White House and the Capitol. Dorothy Height continued as president of NCNW until l998 when she became Chair and President Emeritus. Today, the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site stands as a poignant memorial not only to Bethune herself but the many African American women who worked tirelessly to institute change in American society.

Questions for Reading 4

1. What challenges might Dr. Ferebee and Vivian Carter Mason have faced taking over NCNW while Bethune was still alive?

2. What were some of the accomplishments of each president?

3. How did Dorothy Height change NCNW? What particular challenges did she face as NCNW president during the 1960s?

4. Make a brief timeline of the history of the house. When did it become a National Historic Site? Why was this important?

Reading 4 was adapted from Dorothy Height, Open Wide the Freedom Gates: A Memoir (New York: Public Affairs, 2003); Audrey Thomas McCluskey and Elaine M. Smith, eds. Mary McLeod Bethune: Building a Better World: Essays and Selected Documents (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999); Elaine M. Smith, Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women: Historic Resource Study (Alabama State University, 2003); and Dr. Bettye Collier-Thomas, NCNW: 1935-1980 (Washington, D.C.: The National Council of Negro Women, 1981).

1 As quoted in McCluskey and Smith, eds., 281.

2Dr. Bettye Collier-Thomas, NCNW: 1935-1980 (Washington, D.C.: The National Council of Negro Women, 1981), 19.

Visual Evidence

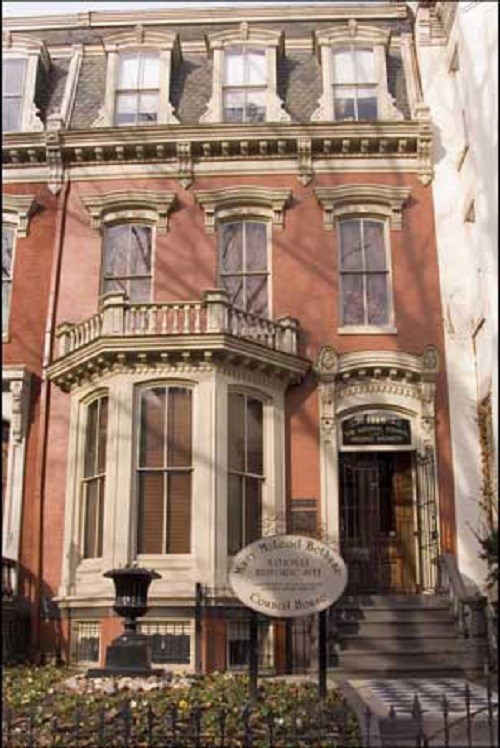

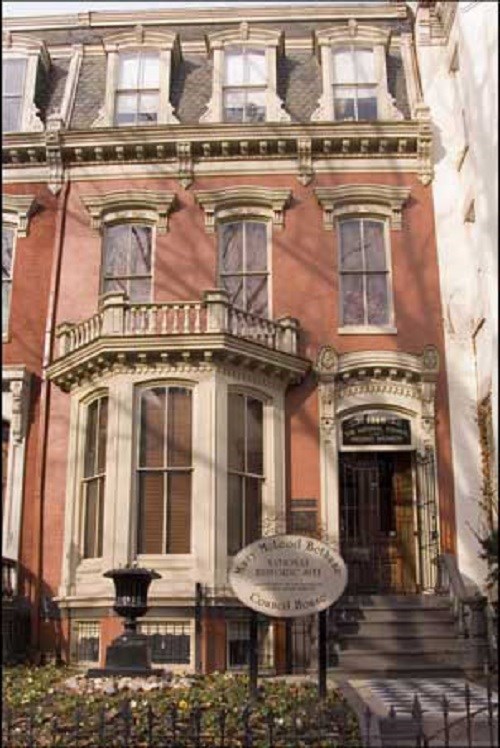

Photo 1: Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site today.

Real estate developer William S. Roose constructed this three-story brick townhouse with raised basement in 1875. Owners during its early years included a reporter for the House of Representatives and a well-known Washington columnist. In 1912, Italian immigrants Alphonso and Anna Gravalles purchased the home and opened up a ladies' tailoring shop. When Mary McLeod Bethune purchased the home from Anna Gravalles in December 1943, the Logan Circle neighborhood was integrated. Aside from serving as NCNW headquarters, the house also was Bethune's D.C residence from 1944 until her retirement in 1949.

The house was built in the Second Empire style, an architectural style popular in the United States from the 1860s through the 1880s. Features of Second Empire include a mansard roof (tall, steeply sloping roof that allowed for added living space on crowded city lots), dormers (windows set into a sloping roof), hooded windows (windows with projecting molding above), decorative brackets, and balustrades.

Questions for Photo 1

1. How would you describe the house? What features of the Second Empire style can you identify?

2. Give a brief history of the house and neighborhood before it became NCNW headquarters. (Refer back to Locating the Site if necessary.)

Visual Evidence

Photo 2: Mary McLeod Bethune (with back to camera) speaking at Council House dedication, October 15, 1944.

Photo 3: Eleanor Roosevelt speaking at Council House dedication, October 15, 1944.

Photo 3: Eleanor Roosevelt speaking at Council House dedication, October 15, 1944.

(Mary McLeod Bethune Council House NHS. Photographer unknown.)During its annual conference in October 1944, NCNW held a ceremony to dedicate the new headquarters at 1318 Vermont Avenue. Major donors and program speakers sat in a semi-circle on the lawn just outside the house. NCNW members and guests filled the rest of the lawn and spilled into the street, which had been closed off by police for the event. One of the speakers proclaimed, "This house has been obtained by the prayers and sacrifice of a few, but the devotion, idealism and ambition which surround it will spread to many; and the inspired efforts which it shall generate in years to come will be felt around the world."1

Questions for Photos 2 and 3

1. Why was this an important day for Bethune and NCNW? Where had NCNW members conducted business prior to the dedication of the Council House?

2. Based on Photo 2, why do you think this ceremony was held outside instead of inside the house?

3. What might Eleanor Roosevelt's presence have meant to NCNW members?

1 Elaine M. Smith, Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women: Historic Resource Study (Alabama State University, 2003), 219.

Visual Evidence

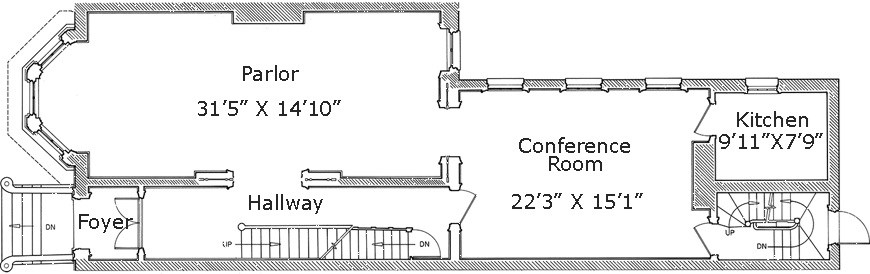

Drawing 1: Council House, first floor plan.

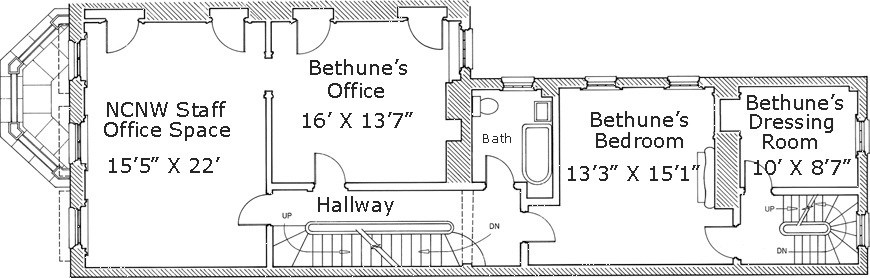

Drawing 2: Council House, second floor plan.

(Historic American Buildings Survey.)

Drawings 1 and 2 are labeled according to how NCNW used the rooms during Bethune's tenancy. NCNW members used the first floor front room or parlor as a reception area and converted the dining room into a conference room and library. In this space, committees met and planned various programs such as the annual conference. The largest room on the second floor became office space for NCNW staff. This floor also housed Bethune's bedroom and private office. Bedrooms on the third floor accommodated African American visitors who were not permitted to stay in most hotels in the segregated city.

Questions for Drawings 1 and 2

1. Compare Drawings 1 and 2 with Photo 1. Where is the front of the house on the drawings?

2. Briefly describe the use of the main rooms of the house.

3. Study the placement and size of the rooms. What might have been some challenges NCNW faced in using a house as a headquarters for a national organization? What might have been some challenges that Bethune faced in living in the same house that served as the headquarters?

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Mary McLeod Bethune in the Council House parlor, 1945

Photo 5: Council House parlor today.

In the living room or parlor, Bethune and NCNW members welcomed many distinguished guests. At Bethune's request, Abe Lichtman, a theater owner, used his own decorator (and his personal funds) to furnish and decorate the room. Using historic photographs and surviving furniture, the National Park Service has recreated the look of the Council House during the period Bethune lived in the house.

Questions for Photos 4 and 5

1. Find the parlor on Drawing 1. Which area of the room is shown in Photos 4 and 5? On what did you base your answer?

2. What purposes did this room serve? Why would it have been important to the members of NCNW to have this room richly furnished and decorated?

3. How does this room demonstrate Bethune's resourcefulness?

4. Compare the two photos. Why would the 1945 photo have been valuable during the restoration?

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: NCNW meeting in conference room of the Council House, ca. 1950.

(Mary McLeod Bethune Council House NHS. Photographer unknown.)

This photo shows NCNW president Dorothy Ferebee and president emeritus Mary McLeod Bethune (white-haired woman seated on right side of table) at a planning meeting at the Council House. This room functioned as the library, conference room, and board room and was the primary space NCNW members gathered for meetings.

Questions for Photo 6

1. Find the conference room on Drawing 1. What are the room's dimensions?

2. Describe the room and its uses. Why do you think the room had to serve multiple functions? Based on what you have learned in the lesson, what were some of the important topics discussed at meetings in this room?

3. What does Bethune's presence at the meeting say about her continued involvement in NCNW affairs even after her retirement?

4. Study the photograph. What information does it provide about the time period?

Putting It All Together

In The Mary McLeod Bethune Council House: African American Women Unite for Change students learn how Mary McLeod Bethune and the National Council of Negro Women promoted political and social change for African Americans. The following activities will help students delve further into aspects of African American and women's history.

Activity 1: The National Council of Negro Women Today

Working in small groups, have students find information on NCNW's website and prepare a written report on the organization's current structure, goals, membership, services, publications, events, and headquarters building. Have the class determine if there is a local section of NCNW in their community. If so, ask a representative to speak to the class about NCNW.

As an alternative, some students might want to conduct further research on Dorothy Height and the activities of NCNW during her presidency (1957-1998).

Activity 2: Taking a Stand

Divide students into small groups and ask each group to select a person Bethune worked with or admired. Groups might choose a person mentioned in this lesson, such as Lucy Laney, Booker T. Washington, Mary Church Terrell, Eleanor Roosevelt, Dorothy Height, Vivian Carter Mason, or Dorothy Ferebee. Or they might work together to identify others who influenced Bethune, such as A. Philip Randolph, W.E.B. Dubois, or a member of the Black Cabinet. The groups should prepare and share with the class an illustrated biography (in the form of a poster, documentary, exhibit, PowerPoint presentation, etc.) on their subject that includes information on that person's efforts to promote equality. To complete the activity, have students discuss how similar or disparate the goals of the various individuals were and the variety of tactics used to further these goals.

Activity 3: Women in National Politics

Ask students to prepare a timeline documenting the role of women in national politics. The timeline should include the names of the first white and black female Congresswoman, Senator, Governor, Supreme Court Justice, and Cabinet member. The timeline should end with the current year and provide statistics on the total number of white and black female Congresswomen, Senators, Governors, Cabinet members, and Supreme Court Justices today. Helpful websites include Women in Congress and Firsts for Women in U.S. Politics. Conclude the activity by holding a classroom discussion to see if students are surprised by what they have learned. To further the activity, students may prepare a short biography on one of the female politicians mentioned in the timeline.

Activity 4: Honoring African Americans and Women in the Local Community

Divide students into small groups and have each group select a site in the community that is associated with African American or women's history (or both). The site could be a school, park, or public building named after a famous African American or woman; a statue; a historic house museum or other place associated with the life of the individual; a museum exhibit, etc. Ask students to conduct a site visit and study the individual to determine what kind of impact the person made on the community and why he/she has been honored in that particular way. The groups should prepare a visual presentation on their findings and share it with the rest of the class. To conclude the activity, have the class work together to create a chart that divides the sites into two categories: symbolic memorials and historic places where the individuals actually lived, worked, etc. Ask students to discuss which type of commemoration they think is more meaningful and why.

Mary McLeod Bethune Council House--

Supplementary Resources

By studying The Mary McLeod Bethune Council House: African American Women Unite for Change students learn about Bethune and the history of the National Council of Negro Women. Those interested in learning more will find that the Internet offers a variety of interesting materials.

National Park Service

Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site

Visit the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site website for operating hours, directions, and other information that will help you plan a visit. The site also provides information on the National Archives for Black Women's History.

The National Council of Negro Women

Today, NCNW consists of more than 39 national affiliates and over 240 sections. NCNW's website features information on the organization's history, mission, structure, and membership. It also includes information on Mary McLeod Bethune.

The Logan Circle Community Association

The Logan Circle Community Association seeks to improve the environment and the quality of life in the Logan Circle area. The association's website features a comprehensive history of the neighborhood.

D.C. Preservation League

The mission of the DC Preservation League is to preserve, protect, and enhance the historic and built environment of Washington, D.C., through advocacy and education.

Experience DC

Experience DC is an online resource created by WETA, a community licensed public broadcasting station in Washington, DC. Click on "African American Heritage" for a biography of Mary McLeod Bethune and for information on segregation and the struggle for civil rights in the nation's capital. "Local History" contains information on the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House and on the Logan Circle neighborhood. "Specialty Tours" includes the U Street neighborhood, as well as an African American Heritage Tour of additional places important to Washington's black community. The tour includes Lincoln Park; the statue of Mary McLeod Bethune in Lincoln Park is the first memorial in the District of Columbia to honor an American woman and the second to honor an African American.

Bethune-Cookman University

The Bethune-Cookman University website includes a biography of Mary McLeod Bethune and a history of the school.

Library of Congress: American Memory Collection

The American Memory Collection website provides access to more than nine million digitized items that document U.S. history and culture. Search "Mary McLeod Bethune" for images of Bethune.

Library of Congress: Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS)/Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) Collection

This website includes additional drawings, photographs, and documentation of the Mary McLeod Council House. You can find the information on the Council House by searching for "Bethune" and selecting the address: 1318 Vermont Avenue, NW, Washington, DC. HABS/HAER is a division of the National Park Service.

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

The Archival Research Catalog (ARC) is the Archive's online catalog. See the African American gallery for a section titled Famous and Notable Individuals.

National Women's Hall of Fame

The National Women's Hall of Fame, located in Seneca Falls, New York, includes exhibits, artifacts of historical interest, and a research library. The website features biographies of more than 200 inductees, including Mary McLeod Bethune and Dorothy Height.

The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project

The Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project website aims to make Eleanor Roosevelt's writings (and radio and television appearances) on democracy and human rights available to a wide audience. The Teaching Eleanor Roosevelt Glossary pages feature information on the National Youth Administration and Mary McLeod Bethune.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

The NAACP website includes a history section, which features a timeline of the organization as well as biographies of several prominent African Americans.

Teach Civics with this Lesson

-

Voting Rights

Voting RightsHow is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting voting rights? What are remedies for low voter turnout?

-

Teaching Engaged Citizenship

Teaching Engaged CitizenshipUse these mini-lessons to fit civics education into a variety of social studies classrooms.

-

First Amendment Freedoms

First Amendment FreedomsHow have people engaged their First Amendment freedoms throughout U.S. history?

Tags

- african american history

- african american education

- black history

- education

- education history

- women’s history

- women's rights

- african american women

- shaping the political landscape

- women in government

- mary mcleod bethune

- mary mcleod bethune council house national historic site

- dc history

- washington dc

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- women's history

- washington d.c.

- art and education

- civics

- civil rights

- early 20th century

- late 20th century

- 19th amendment

- womens history

- women leaders

- women and education

- women and politics

- civil rights history

- twhplp

- etc aah

- wwii aah