Last updated: April 2, 2025

Article

Post World War II Food

World War II brought several changes to what and how we eat. For example, members of the military traveled the globe during World War II, encountering different cuisines. When they returned, they brought back memories of those dishes. French, Italian, and Chinese food soon became popular in America beyond immigrant neighborhoods like Chinatowns and Little Italys.[1]

Other changes were spurred by foods included in military rations and food produced using technologies developed during the war. There are also recipes born from rationing and Victory gardens that “stuck.”

US Army Signal Corps, 1943.

The Taste of Rations

The US military had a system of rations for feeding troops in the field. This system was designed to “maintain the health and effectiveness” of the troops.[2] K-Rations and C-Rations were both issued to troops in combat. They provided between 3,000 and 3,600 calories per day. Within these rations, soldiers found candy, freeze dried coffee, and canned meat.[3] In civilian life, we know these as M&Ms, instant coffee, and Spam.

M&M’s

M&Ms – the chocolate candy surrounded by a hard candy shell – were patented by Forrest Mars on March 1, 1941. By making a deal with Bruce Murrie of the Hershey Corporation, Mars had access to rationed chocolate. M&M candies, named for the first initials of each partners’ last name, went on sale late in 1941. When the US went to war, Mars got an exclusive contract with the US military to provide M&Ms for C-Rations. The candy was perfect for this use – they traveled well, and because of the candy coating, did not melt at high temperatures. Soldiers returned with a taste for the colorful candies, and M&Ms became available to the general public.[4]

Copyright Nestlé S.A. Collection of the Nestlé Historical Archives.

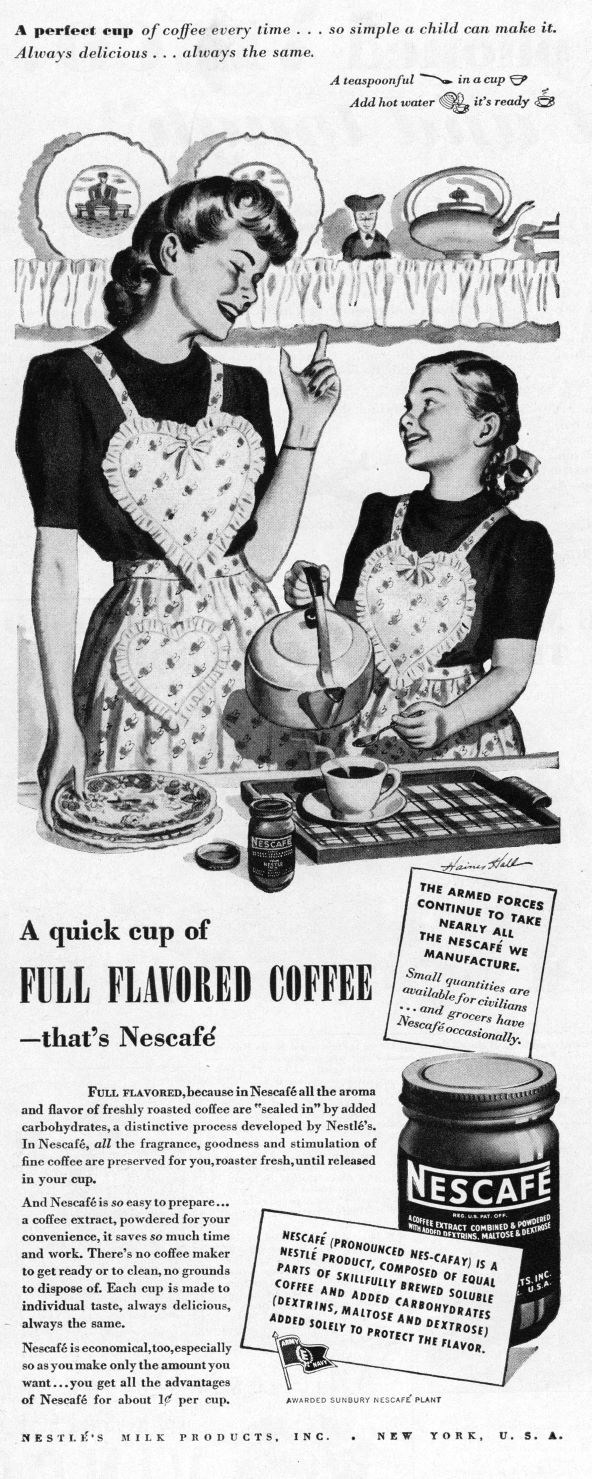

Instant Coffee

Instant (or soluble) coffee existed before World War I. It was a dried, concentrated coffee extract that you prepared by adding hot water to it. In 1936, the Nestlé company developed their Nescafé brand instant coffee. Spurred by a desire to transform surplus coffee beans from Brazil into a quick-to-use, low-waste product, Nestlé discovered a way to make a more flavorful instant coffee. They called it Nescafé, a combination of the words Nestlé and café.[5] In 1941, Nestlé began supplying Nescafé for inclusion in American field rations. When American soldiers returned home after the war, they had a taste for the instant coffee.[6]

After the war ended, Nestlé provided Nescafé for the care packages sent to Europe and Japan. These packages provided food and other necessities while the countries got back on their feet. This boosted global demand for Nescafé.[7] There is, however, more to the story. During the war, Nestlé companies supplied both the Axis and the Allies. In 2000, the company agreed to pay millions of dollars to settle claims that a German company they purchased used forced labor during the war. [8]

Spam

Spam is a tinned pork product. It was first introduced by the Hormel company in Austin, Minnesota in 1937. It became entrenched in American culture in World War II, when the US military contracted with Hormel (and other canned meat providers) to supply it for military rations. Hormel estimates they shipped more than 100 million pounds of Spam during the war.[9] Not all those who encountered it loved it – or even enjoyed it. Hormel kept a “scurrilous file” of hate mail from service members who were eating it three times a day. Others refused to even have it in their house decades after the war.[10]

For those on the Pacific home front (including American Samoa, the Philippines, Guam, and Hawai’i), Spam holds a special place. American GIs would share their rations with locals, and it was available for purchase in the post exchanges.[11] When the Japanese incarceration camps in the Philippines and on Guam were liberated by American forces, soldiers found starving prisoners. Many shared their rations on the spot. And with the extensive damage from the war, many Pacific islands were unable to provide enough food for their residents. There were also delays in the transition to commercial shipping, further limiting choices. To feed people, many of whom were on the point of starvation, the US issued rations, including Spam.[12]

“The Chamorro people have this love of Spam, corned beef, and pork and beans because that was the food they were given right after the war… We who were born right after the war, we remember. We grew up eating it every day.” – Linda Calvo, Guam[13]

Photo courtesy of Jade Ryerson. All Rights Reserved.

“to the people of Hawaii, Spam meant precious nourishment in a time of uncertainty and chaos. Thus, they prepared it with an immense amount of love. We cut it up, we sautéed it, we simmered with shoyu and sugar; we turned it into something else that was beautiful.”[14]

In Hawai’i, Spam became popular after the US restricted the fishing industry during the war. They were afraid residents would use the boats to communicate with the Japanese. Because there were so many people of Japanese descent living in the Hawaiian Islands, the federal government could not incarcerate all of them (like they did for those living along the west coast of the mainland). Instead, the US imposed martial law. Spam and other shelf-stable, shippable foods replaced fresh fish in the Hawaiian diet.[15]

Regardless of how it was introduced, Spam has remained an important part of the culture of these places ever since. In Guam, each person eats an average of 16 cans of spam per year, while Hawaiians consume an average of 5 cans per year. It has also been incorporated into regional menus at fast food restaurants like McDonald’s and Wendy’s. For example, you can order Spam, Eggs, and Rice for breakfast in Hawai’i, American Samoa, and Guam.[16] Importing Spam to Pacific islands like the Philippines is expensive. Seeing a can of Spam in these homes suggests they can afford it, or that they have connections to those in the US who send it.[17]

Among Spam’s benefits is that it is shelf stable, and can be eaten cooked or straight out of the can, in case of emergencies like hurricanes.[18] It’s downsides include its role in the dependence of these places on imported canned and processed foods, and the accompanying health impacts such as the prevalence of diabetes and heart disease in these places since the war.[19]

Photo by Bing Ramos, Quezon City, Philippines. CC-BY-SA 2.0.

Recipes

Spam Fried Rice (Guam): Fry half of a chopped onion until soft. Then add half a can of Spam, cubed, and fry until golden brown. Add 3 cups of cooked rice and fry until it is shiny (about five minutes) before adding 2 teaspoons of soy sauce and frying an additional 5 minutes. Serve on a platter topped with two scrambled eggs (chopped up) and chopped green onions, if desired.[20]

Spam Musabi (Hawai’i): a “sushi” of Spam, sometimes using the Spam can as a form to shape it. There are many versions; this one makes 2 servings, and is modified from the Spam website: In a large skillet, fry two slices of Spam (3/8” thick each) until crispy on each side. Drizzle with a glaze of your choice (for example, a soy-based sauce or sweet ginger sesame sauce – you can buy or make your own). Line the inside and bottom of an empty Spam can that has both ends removed with plastic wrap. Press 1.5oz of cooked white rice (or sushi rice) firmly into the can. The rice can be seasoned with toasted sesame seeds and furikake if desired (furikake is a Japanese rice seasoning. You can buy it, or make your own). Place a slice of the cooked Spam on top of the rice, and press firmly. Remove from the can, and repeat for the second slice. Cut two strips from a sheet of nori (seaweed). If you like the taste of nori, you can cut a wider strip. With the strip of nori laying shiny side down, top it with the pressed Spam and rice. Wrap the nori around it, and repeat with the second piece. Serve immediately.[21]

Spamsilog (Philippines): a combination of fried Spam, garlic fried rice, and egg often served for breakfast, especially with banana ketchup.[22]

Wartime Food Innovations

Most wartime food innovations were geared to provide the military with nutritious, easy-to-ship, and long-lasting foods for rations. Some of the innovations made it into production during the war years; others did not. Regardless, several, including powdered cheese and orange juice concentrate went on to shape the civilian food landscape.

Collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Herbert Waide Hemphill, Jr. and museum purchase made possible by Ralph Cross Johnson (1986.65.277).

Powdered Cheese

Cheese was a convenient way to ship dairy.[23] The military was always looking for ways to reduce the weight and volume of foods as ways to increase how much could be transported at one time.[24] In 1943, USDA scientist George Sanders developed the first real cheese powder. Previous attempts to dehydrate cheese had failed, because the application of heat caused the milk fats to melt and separate. Sanders solved the problem with a two-step process. By first grating the cheese and drying it at a low temperature. This resulted in a barrier forming around the fats. In the second step, the cheese was ground into a powder and dehydrated again before being pressed into cakes.[25]

When the war ended in 1945, the military had huge stockpiles of food, including powdered cheese. The government liquidated these stockpiles, sometimes for pennies on the dollar, to private industry. Companies like Frito (later Frito-Lay), Kraft, and others found ways to use these wartime products. In 1948, the Frito company coated puffed cornmeal pieces with dehydrated cheese, and Cheetos were born.[26]

Orange Juice Concentrate

Research began in 1942 for a way to economically ship orange juice to soldiers on the front lines. It was important that they got enough Vitamin C to say healthy. The military had been issuing lemon crystals, but because of their unpleasant taste, soldiers tended to ignore them. Initial attempts to concentrate orange juice left it tasting bland. In 1945, just as the war was ending, the process of making tasty orange juice concentrate was perfected. Fresh juice added to the concentrate restored the taste of fresh juice. The resulting process removed 80% of the water in orange juice. When ready to drink, users only had to add back the water to the frozen concentrate. Producers quickly pivoted the product to the consumer market, and Minute Maid hit the shelves.[27]

Photo copyright Lynn Gilbert, CC by SA 4.0

Ration Recipes

After the war and rationing ended, Americans still faced some challenges in grocery shopping. A lot of foods were being sent to Europe and elsewhere to feed Allies whose farmlands had been devastated or neglected. As food choices and availability improved after the war many Americans compensated for wartime scarcity by eating meat- and butter-rich meals. Grilling a steak became the height of entertaining.[28] But some wartime foods (including some with roots in earlier times of shortage, like the Great Depression) stuck. Among these are stuffed peppers; Kraft macaroni and cheese; and fruit cobbler.

Stuffed Peppers

Stuffed peppers (and their close cousins, stuffed cabbage leaves and stuffed tomatoes) were filled with a mixture of a little ground beef extended with rice, seasonings, and other vegetables (which in season, could come right from the cook’s Victory garden). Ground beef was popular during wartime, because it needed fewer ration stamps than other cuts of meat. In one stuffed pepper recipe, a quarter pound of beef made four servings of stuffed peppers.[29]

Kraft Macaroni and Cheese

Kraft macaroni and cheese was invented in 1937 during the Great Depression, but its popularity boomed during the War. The powder is a cheese sauce that has been partially defatted and dehydrated. By adding milk and/or butter during cooking, you replace the moisture and fats.[30] Kraft macaroni and cheese was inexpensive, filling, and you could get two boxes for a single ration point. It was also quick and easy to make – an important consideration as women who were in the workforce had little time at home.[31] Kraft sold 50 million boxes of its macaroni and cheese during World War II.[32]

Wikimedia Commons.

Fruit Cobbler

Fruit cobblers and crisps became popular during World War II. Seasonal fruits made up most of the dish, needing only a little rationed sugar. These desserts had no bottom crust, saving on the butter, lard, or shortening needed. The thin toppings of cake, biscuit, pastry, or crumble used very little fat. The result was a ration-friendly dessert that is still popular.[33]

Dishes like those described here – from Spamsilog to Fruit Cobbler -- have become staples in American culture. The reasons may include being comfort foods, being inexpensive or easy options when money or time was tight, or perhaps from a sense of patriotism or nostalgia.

** Any mention of trade names does not imply endorsement of these brands, companies, or products. They are included solely for historical understanding.

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] Hayes 2000: 217; Library of Congress n.d. a, n.d. b.; Michigan Radio 2014; Tunc and Babic 2017.

[2] Mason, Meyer, and Klicka 1982: 6.

[3] Mason, Meyer, and Klicka 1982: 25-31.

[4] de Salcedo 2015: 201; Massachusetts Institute of Technology n.d.; Nieburg 2016. Bruce Murrie was son of William Murrie, president of the Hershey Chocolate Corporation at the time. Hershey also made D-Rations, nutrition-packed chocolate bars for emergencies that were designed not to melt. At the time of the partnership, Hershey’s operations were located entirely at Hershey, Pennsylvania. The Hershey Community Building (2 Chocolate Ave., Hershey, PA) was listed in the NR October 15, 1980. The home of Hershey's founder, Milton S. Hershey (100 Mansion Rd. E, Hershey, PA) was listed on the NR February 7, 1978 and designated an NHL on May 4, 1983.

[5] Koehler 2017; Nescafé n.d.; Thorne 2020. They used the spray-drying technique that they had originally developed for creating powdered milk in World War I, and added carbohydrates to retain the coffee flavor.

[6] Nescafé n.d.; Rothfield 2022; Thorne 2020.

[7] Nescafé n.d.

[8] Associated Press 2000; Owles 2017.

[9] DeJesus 2014; Heydt 2006.

[10] DeJesus 2014; Frisino 2000.

[11] Berbey and Longoria 2022; Lopez 2022; Mitchell 2021.

[12] DeJesus 2014; Mora 2017; Tolentino 2023.

[13] Mora 2017.

[14] Noguchi 2016.

[15] DeJesus 2014.

[16] Berbey and Longoria 2022; Mora 2017; Noguchi 2016; Tolentino 2023.

[17] Lopez 2022; Mitchell 2021; Tolentino 2023.

[18] Mora 2017.

[19] Lopez 2022; Noguchi 2016.

[20] Guthertz 1985.

[21] Modified from Spam 2023.

[22] Valencia 2016.

[23] Hayes 2000: 125.

[24] de Salcedo 2015: 144.

[25] de Salcedo 2015: 144-146.

[26] de Salcedo 2015: 146.

[27] de Salcedo 2015: 199; Smithsonian Institution 2023.

[28] Hayes 2000: 217.

[29] Hayes 2000: 117, 163.

[30] Miller 2020. The defatting process eliminated the issue of separation that George Sanders later solved for dehydrated cheese.

[31] Chicago History Museum 2021; Miller 2020.

[32] National World War II Museum 2020.

[33] Hayes 2000: 161.

Associated Press (2000) “Nestle Pays $14.6M for Holocaust.” Associated Press, August 28, 2000.

Berbey, Gabrielle and Julia Longoria (2022) “Uncle Spam.” The Experiment (podcast), February 3, 2022.

Chicago History Museum (2021) “Say Cheese!” Chicago History Museum.

DeJesus, Erin (2014) “A Brief History of Spam, an American Meat Icon.” Eater, July 9, 2014.

de Salcedo, Anastacia M. (2015) Combat-Ready Kitchen: How the U.S. Military Shapes the Way You Eat. Current, New York.

Frisino, Denise (2020) “Rationing – A Fair Share for All of Us.” Denise Frisino, April 6, 2020.

Guthertz, Judith (1985) “Spam Fired Rice: Recipe.” Guampedia.

Hayes, Joanne L. (2000) Grandma’s Wartime Kitchen: World War II and The Way We Cooked. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Heydt, Bruce (2006) “Spam Again.” America in WWII, June 2006.

Koehler, Jeff (2017) “In WWI Trenches, Instant Coffee Gave Troops A Much-Needed Boost.” The Salt, National Public Radio, April 6, 2017.

Library of Congress (n.d. a) “A City of Villages.” Immigration and Relocation in US History.

--- (n.d. b) “Building Communities.” Immigration and Relocation in US History.

Lopez, Mary Stachyra (2022) “One Community’s Complicated Relationship With Spam.” The Atlantic, March 29, 2022.

Mason, Vera C., Alice I. Meyer, and Mary V. Klicka (1982) “Summary of Operational Rations.” United States Army Natick Research & Development Laboratories, Food Engineering Laboratory, Technical Report, June 1982.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (n.d.) “Forrest Mars, M&M’s.” Lemelson-MIT.

Michigan Radio (2014) “How World War II Changed American Food.” Michigan Radio, November 18, 2014.

Miller, Jeffrey (2020) “How Boxed Mac and Cheese Became a Pantry Staple.” Smithsonian Magazine June 12, 2020.

Mitchell, Pilar (2021) “How Filipinos Regained Their Independence and Made Spam Their Own.” Special Broadcasting Service (Australia), June 2, 2021.

Mora, Kyla P. (2017) “The Wartime Alliance of Guam and Spam, Generations Later.” Pacific Daily News, July 22, 2017.

National World War II Museum (n.d.) “Rationing.” National World War II Museum. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/rationing

Nescafé (n.d.) “Understanding Coffee: The History of Nescafé.” Nescafé.

Nieburg, Oliver (2016) “Untold War Stories: Mars and M&M’s Military History.” Confectionary News, November 10, 2016.

Noguchi, Mark “Gooch” (2016) “The History Behind Why Hawaiians Are Obsessed With Spam.” Munchies, Food by Vice, January 7, 2016.

Owles, Eric (2017) “How Nestlé Expanded Beyond the Kitchen.” Dealbook, New York Times, June 27, 2017.

Rothfeld, Anne (2022) “Coffee Rationing During World War II.” Circulating Now: From the Historical Collections of the National Library of Medicine, November 23, 2022.

Smithsonian Institution (2023) “Minute Maid Concentrated Orange Juice Can.” Smithsonian Institution.

Spam (2023) “Spam Musubi.” Spam.com.

Thorne, Stephen J. (2020) “Coffee: The Soldier’s Drink of ‘Choice and Remembrance.’” Legion April 1, 2020.

Tolentino, Dominica (2023) “CHamoru’s Love of Spam.” Guampedia, March 27, 2023.

Tunc, Tanfer Emin and Annessa Ann Babic (2017) “Food on the Home Front, Food on the Warfront: World War II and the American Diet.” Food and Foodways 25(2): 101-106.

Valencia, Chase (2016) “How Traders, Travelers and Colonization Shaped Filipino Cuisine.” The Migrant Kitchen, KCET (Public Media Group of Southern California), September 29, 2016.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

-

The Home Front During World War IICanning and Food Preservation

The Home Front During World War IICanning and Food PreservationPlanting Victory Gardens was only part of the work. Efficiently and safely preserving that bounty for later use was crucial.

-

The Home Front During World War IIMaria Ylagan Orosa

The Home Front During World War IIMaria Ylagan OrosaMaria is best known as the inventor of banana ketchup. Her impact on Philippine life and her heroism on the home front is much greater.

-

The Home Front During World War IIRestrictions and Rationing

The Home Front During World War IIRestrictions and RationingWartime shortages meant people had to do without or make due. Nylons, canned dog food, and sugar were some of the goods in short supply.

Tags

- world war ii

- wwii

- world war 2

- ww2

- foodways

- international relations

- immigration and migration

- victory garden

- victory gardens

- military history

- history of food

- rationing

- minnesota

- austin

- american samoa

- philippines

- hawaii

- asian american and pacific islander history

- asian american pacific islander history

- indigenous history

- history of science