Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

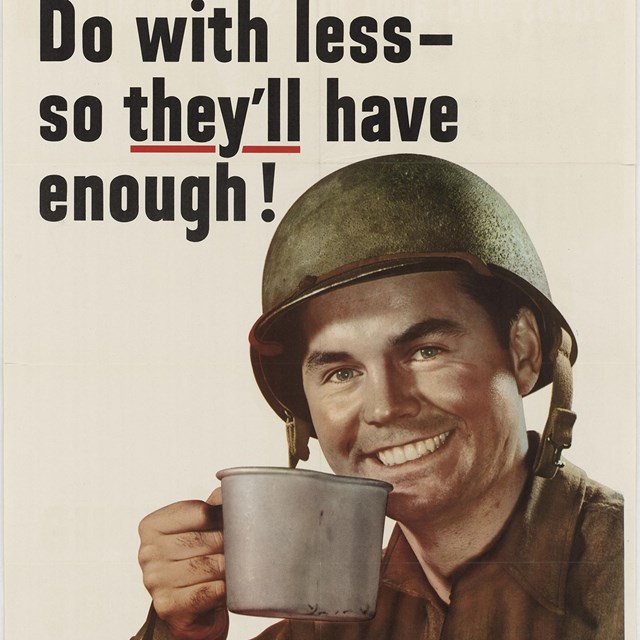

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 513566).

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/2017821960).

Like planting Victory Gardens, preserving the harvest was also presented as patriotic. Extensive resources were available from the government, local agricultural extension services, and businesses.[2] Preservation could take several forms: drying (dehydrating), freezing, pickling, and canning. Each of these approaches had pros and cons, and were not equally suitable for all products. For example, sources recommended drying corn because it retained good flavor and was a challenge to can.[3] Sources also discouraged canning lettuce (gross) and canning vegetable mixes (too dangerous).[4]

Drying did not need any rationed items used in canning (such as sugar, as well as the metal and rubber seals). Options included sun-drying, oven drying, and drying cabinets or racks.[5] Freezing did not become popular until after the war, when manufacturers sold fridges with larger freezers. Before that, people rented space in large commercial cold storage facilities.[6] Some produce – especially root vegetables – stored well in cool, dark places like root cellars, or even stored in the ground over winter.[7] By far the most popular means of preservation was canning.[8]

Canning

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 515098).

Victory Gardeners canned fruits, vegetables, and even meats.[9] One source recommended canning 85 to 115 quarts of produce per person in a family to last over the winter.[10] Canning home-raised meats like rabbit and chicken was one way to extend meat rations. To support those working to preserve their own foods, canners could apply for up to an extra 20 pounds of sugar. This amount, however, was not guaranteed, and depended on availability.[11]

Canning was most commonly done using specialty glass canning jars.[12] Key to successful canning was ensuring that jars were sterile and applying high heat to kill all the bacteria in the food.[13] If bacteria was not properly eliminated in the airtight containers, botulism and other food poisoning was possible.[14] In general, only acidic foods like tomatoes and fruits could be canned using a hot water bath. Other vegetables and meats needed to be preserved using pressure canners. The pressure allows water to boil at a temperature above its usual boiling point, and thus better able to kill the bacteria.[15] By following the best available science and being aware of the signs of spoilage, successful canning was possible. The goal was to put up enough nutritious fruits, vegetables, and meat to last to the next growing season. There were lots of resources available to ensure success. These included publications and classes from governments, communities, newspapers, magazines, and even businesses.[16] In the Philippines, Maria Orosa and her team of educators taught Filipinos how to preserve local foods to reduce reliance on imports.[17]

Many homes already had a pressure cooker that they could use for canning. These folks were fortunate. Pressure canners and cookers were made of aluminum. As the US joined World War II, the government stopped their production and rationed the available supply. Those without were urged to borrow from their friends, family, or neighbors. Failing that, they were encouraged to use the resources at a community food preservation center (also known as a community cannery). After pressure from the US Department of Agriculture, the War Production Board eased restrictions. In 1944, they capped production of pressure canners at 40,000; in 1945, they raised that number to 630,000.[18]

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/2017847239).

Community Canneries

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/2017775514).

Community canneries served (and continue to serve) many purposes. They are places where people learned about canning and spent time with community. They also had access to equipment they may not have had at home, and were able to can a lot of product in a short amount of time. There were also knowledgeable staff or volunteers ensuring safety. Equipment available included home- to industrial-size pressure canners, sealers, and large workspaces.[19]

The history of community canneries goes back to the late 1800s, places where neighbors would gather to preserve their harvests. Their use expanded during World War I and the Great Depression, as families grew War Gardens and worked to feed themselves through the 1930s. In World War II, with government subsidies to build and manage them, the number of community canneries expanded and saw considerable use. Some, like the cannery at Michigan State University, were privately funded – in this case, by Henry Ford. Canning jars likely associated with this cannery were recovered during archaeological excavations at the school.[20] It was common for community canneries to be located within schools or on their grounds. This let educators use them for training, and they could also be used to preserve food for the students. Others could be found in private homes, church kitchens, and converted commercial plants. The US Department of Agriculture provided extensive information on how to start and manage a wartime community cannery. By the end of the War, there were more than 3,800 community canneries across the United States. Home gardeners using community canneries and other facilities had to get a permit. This eliminated confusion between who was canning for home use and who was using the facilities for resale / commercial canning.[21]

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/90709140).

Their number declined after the War, as subsidies disappeared and freezing technology improved.[22] Some survived, and there has been waxing and waning in their numbers, but community canneries continue to exist.[23] Until recently, the Keezletown Community Cannery in Virginia was one of the longest-running community canneries. It opened in 1942 in the basement of the local elementary school and continued to operate year after year on the school grounds. In the spring of 2019, operations ceased. The school needed the cannery building to house a growing student population, and at the time there were plans to reopen it elsewhere.[24]

Storage and Use

After preparation, canned foods were kept in a cool, dark location until needed. In 1943, 75% of American homemakers put up 4.1 billion containers of food, averaging 165 jars each. They preserved another 3.5 billion quarts of food in 1944. This represented nearly half of all canned vegetables and 2/3 of canned fruits for civilian use that year.[25] People took great pride in the results of their canning efforts. This, plus the uncertainty of wartime, led to a problem of people not using their preserved foods. “There are two mistakes you can make in using your home-canned foods,” wrote Good Housekeeping. “The first – serving favorites too often. The second – using your supply so sparingly that you’ll have some left over when the summer’s garden crop comes along.”[26]

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 513787).

In planning the Victory Garden program, the government intended that the harvest be used by those who produced it. If you had more than you needed, you could give away a small amount.[27] Some shipped canned foods to their loved ones serving overseas. Julie A. Lenard from Middletown, Pennsylvania described her father (stationed in France) asking for a chicken:

So Mom prepared and canned a chicken in a glass jar and sent it off to Dad. Meanwhile he was sent to… New Jersey for treatment of an injury. He arrived back home… when the chicken finally caught up to him. So together, Mom and Dad enjoyed the chicken that had traveled half way around the world.” Julie A. Lenard, Middletown, Pennsylvania, telling the story of her mother, Martha Tittiger [28]

After the War

Even after the war ended, there was a push to continue Victory Gardening and canning. The United States was sending food and supplies overseas to help feed war-torn countries while they got back on their feet. (Britain’s food supply system was so damaged by the war that many items remained rationed into the early 1950s).[29] People continue to grow and preserve their own foods, though most not with the same urgency of the war years.[30]

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History’s cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] United States Department of Agriculture 1943b: 18.

[2] National Agricultural Library n.d.; National Women’s History Museum 2017.

[3] United States Department of Agriculture 1943a.

[4] United States Department of Agriculture 1944: 15. They recommended canning individual types of vegetables separately, and combining when used.

[5] United States Department of Agriculture 1942: 1, 1943a.

[6] Hayes 2000: 31, 54-55.

[7] United States Department of Agriculture 1943: 9.

[8] Hayes 2000: 53.

[9] Stanley et al. 1942. Canning meats, which is often done using fats, is also called potting.

[10] Ellis 1944.

[11] Hayes 2000: 77; National Agricultural Library n.d.; National Women’s History Museum 2017.

[12] Some places used tin cans throughout the war, often because of transportation access issues. For example, see “Jeffersontown, Kentucky. The Jefferson County community cannery, started by the WPA (Work Projects Administration), now conducted by the state vocational education department. Women pay three cents each for cans and two cents per can for use of the pressure cooker. Women preparing cans to be heated and cooked.” Photo by Howard R. Hollem, Office of War Information, June 1943. Collection of the Library of Congress.

[13] Smithsonian Gardens n.d.

[14] Hayes 2000: 54.

[15] United States Department of Agriculture 1944: 2.

[16] Hayes 2000: 54; Midland Journal 1944; National Agricultural Library n.d.; Stanley et al. 1942: 46-48; Toepfer and Reynolds 1947; United States Department of Agriculture 1943b: 9, USDA 1943c, 1944; Wassberg Johnson 2022.

[17] Gingrich 2020.

[18] National Agricultural Library n.d.

[19] Coffey and Sternberg 1977: 372; Furman 1941; Jenner 2014; National Agricultural Library n.d.; National Women’s History Museum 2017.

[20] Bright 2016. For information on identifying and dating canning jars, see Brantley 1975; Lindsey 2020; Matchar 2020; Toulouse 1971.

[21] Coffey and Sternberg 1977: 372; Furman 1941; Keezletown Community Cannery 2011; United States Department of Agriculture 1941.

[22] Coffey and Sternberg 1977: 372; Jenner 2014; Russell 1947: 90-91.

[23] Evans 2020.

[24] Keezletown Community Cannery 2011; Redeemer Classical School 2020. There are a handful of community canneries represented in the National Register of Historic Places. These include: the Draper Cannery in Draper, Virginia, a contributing property to the Draper Historic District, listed on February 21, 2020; Houston High School in Houston, Missouri which operated a community cannery during the War, listed on February 12, 2009; and the Central High School in Painter, Virginia also the site of a World War II community cannery, listed on August 16, 2010.

[25] National Agricultural Library n.d.; Sundin 2023; Toepfer and Reynolds 1943: 787.

[26] Hayes 2000: 54.

[27] Russell 1947: 90.

[28] Hayes 2000: 56.

[29] Imperial War Museums 2023.

[30] Matchar 2020.

Brantley, William F. (1975) A Collector’s Guide to Ball Jars. Rosemary Humbert Martin, Muncie, IN.

Bright, Lisa (2016) “Canning on Campus.” MSU Campus Archaeology Program, February 16, 2016.

Coffey, F. Aline and Roger Sternberg (1977) “Resurgence of Community Canneries.” In United States Department of Agriculture Yearbook of Agriculture: Gardening for Food and Fun, United States Department of Agriculture, p. 372-377. Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

Ellis, Alva (1944) The Victory Garden Guide: Planting Date : How to Plant : Proper Care : Insects and Their Control. Self-published, April 1944.

Evans, Hannah J. (2020) “Grow All You Can, And Save All You Grow: Innovation and Tradition at the Prince Edward County Community Cannery.” MA thesis, Department of American Studies, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Furman, Bess (1941) “Community Food Preservation Centers.” Bureau of Home Economics, United States Department of Agriculture, Miscellaneous Publication No. 472.

Gingrich, Jessica (2020) “Maria Ylagan Orosa and the Chemistry of Resistance.” Lady Science, July 23, 2020.

Hayes, Joanne L. (2000) Grandma’s Wartime Kitchen: World War II and The Way We Cooked. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Imperial War Museums (2023) “What You Need To Know About Rationing In The Second World War.” Imperial War Museums.

Jenner, Andrew (2014) “Canned: A WWII-Era Community Cannery Hangs on in Rural Virginia.” Modern Farmer, October 14, 2014.

Keezletown Community Cannery (2011) “History.” Keezeltown Community Cannery (archived).

Lindsey, Bill (2020) “Bottle Typing / Diagnostic Shapes : Food Bottles & Canning Jars : Canning Jars.” Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information, Society for Historical Archaeology and Bureau of Land Management.

Matchar, Emily (2020) “A Brief History of the Mason Jar.” Smithsonian Magazine, August 26, 2020.

Midland Journal (1944) “Blitz Bacteria Battalions by Following Simple Rules.” Midland Journal (Rising Sun, MD) September 1, 1944, p. 5. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

National Agricultural Library (n.d.) “How Did We Can? The Evolution of Home Canning Practices: A National Agricultural Library Digital Exhibit : World War II.” United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Library.

National Women’s History Museum (2017) “Food Rationing and Canning in World War II.” National Women’s History Museum, September 13, 2017.

Redeemer Classical School (2020) “Keezletown Community Cannery Finds a New Home.” Redeemer Classical School, May 11, 2020.

Russell, Judith (1947) “Processed Foods Rationing.” In Judith Russell and Renee Fantin (1947) Studies in Food Rationing, Office of Temporary Controls, Office of Price Rationing, p. 71-182.

Smithsonian Gardens (n.d.) “Gardening for the Common Good.” Cultivating America’s Gardens, Smithsonian Libraries Exhibitions.

Stanley, Louise, Mabel C. Stienbarger, and Dorothy Esther Shank (1942) Home Canning of Fruits, Vegetables, and Meats. United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Human Nutrition and Home Economics, Farmers’ Bulletin: Number 1762. Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

Sundin, Sarah (2023) “Make It Do: Rationing of Canned Goods in World War II.” Today in World War II History, February 27, 2023.

Toepfer, Edward W. and Howard Reynolds (1947) “Advances in Home Canning.” In United States Department of Agriculture, The Yearbook of Agriculture 1943-1947: Science in Farming, p. 787-794. Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

Toulouse, Julian Harrison (1971) Fruit Jars. Thomas Nelson, Camden, NJ.

United States Department of Agriculture (1944) Home Canning of Fruits and Vegetables: Seven Points for Success. United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Home Nutrition and Home Economics, May 1944. Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

--- (1943a) Oven Drying: One Way to Save Victory Garden Surplus. United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Human Nutrition and Home Economics, August 1943. Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

--- (1943b) Victory Garden Leader’s Handbook. United States Department of Agriculture. Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

--- (1943c) Take Care of Pressure Canners. United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Human Nutrition and Home Economics, September 1943. Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

--- (1942) Drying Foods for Victory Meals. United States Department of Agriculture. Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

--- (1941) Community Food Preservation Centers. United States Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Home Economics. Collection of the National Agricultural Library.

Wassberg Johnson, Sarah (2022) “World War Wednesday: Home Canning Don’ts.” Food History Blog, September 7, 2022.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front During World War IIFood Rationing

The Home Front During World War IIFood RationingThe military's need for food and packaging, limited shipments from overseas, and agricultural laborers going to war meant food was rationed.

-

The Home Front During World War IIRationing, Recycling, & Victory Gardens

The Home Front During World War IIRationing, Recycling, & Victory GardensAs the US joined the war, huge amounts of resources were needed. This meant that civilians had to do without or find other means.

-

The Home Front During World War IIServel Co. & History of Refrigeration

The Home Front During World War IIServel Co. & History of RefrigerationDuring World War II, Servel switched from civilian goods to full-scale war production. And they worked to stay relevant with consumers.