National parks, especially those far from urban areas, are some of the last refuges of dark night skies.

Abstract and key words

Abstract: Night skies are increasingly recognized as an important park resource that demands more management attention. Management of night skies can be guided by a management-by-objectives framework that requires formulation of indicators and standards of quality. Two surveys were conducted at Acadia National Park to identify indicators and standards for stargazing. The first survey used an importance –performance approach and documented light pollution as an important indicator variable. The second survey used a normative approach and visual simulations to identify a range of standards of quality for light pollution. This program of research was designed to help inform management of night skies at Acadia and other parks.

Key Words: Acadia National Park, indicators and standards, night skies, stargazing

Night skies as a “new” park resource

THE FOCUS OF THE FIRST NATIONAL PARKS ESTABLISHED IN THE LAST HALF OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY was on "scenery," or the vast, sublime landscapes of the American West. In the early 20th century, the significance and meaning of national parks was extended in two important ways. First, historical and cultural resources were recognized as increasingly important, and additional national parks were created under the auspices of the Antiquities Act (Public Law 59-209, 34 Stat. 225, 8 June 1906) and other programs. Second, the birth of the modern science of ecology suggested that the landscapes of national parks comprise geologic and biologic resources that are intertwined to form complex ecosystems. This ecological reality implied that national parks be established and managed in a more holistic way and that the National Park System be extended to encompass the full array of North American ecosystems and associated biodiversity. In the latter half of the 20th century, the recreational values of national parks were given growing emphasis as manifested in the Mission 66 program, an initiative that funded park visitor centers and other infrastructure designed to accommodate rapidly expanding visitation. At the transition to the 21st century, the definition and significance of national parks is being extended again to include a host of “new” park resources, including a suite of ecological services (e.g., air and water quality, climate stability), natural sounds (the sounds of nature uninterrupted by human-caused noise) and natural darkness (darkness undiminished by artificial light) (https://www.nature.nps.gov/sound_night/). This article focuses on the latter, specifically night skies.

The emerging importance of natural darkness and night skies is a function of the intersection of a growing consciousness about their values and a crisis over their rapid disappearance. For millennia, people have “gazed upon the cosmos” in their enduring efforts to understand both the physical and metaphysical worlds, and this suggests that night skies are an important cultural resource (Bogard 2013). Human culture is conventionally organized around the rhythms of the sun, moon, and stars; observations of the night sky are embodied in the religions and mythology of cultures around the world; and the celestial world has been the inspiration for art, literature, and other forms of cultural expression (Rogers and Sovick 2001a; Collison and Poe 2013). Modern science has extended the importance of night skies by demonstrating the relevance of darkness in the biological world; many of the world’s species rely on the absence of artificial light for breeding and feeding patterns and other behaviors (Lima 1998; Witherington and Martin 2000; Le Corre et al. 2002; Alvarez del Castillo et al. 2003; Longcore and Rich 2004; Pauley 2004; Perry and Fisher 2006; Rich and Longcore 2006; Wise and Buchanan 2006; López and Suárez 2007; Navara and Nelson 2007; Chepesiuk 2009; Luginbuhl et al. 2009). Light pollution can even affect humans through sleep disturbance and other health effects (Nicholas 2001; Clark 2006; Chepesiuk 2009).

Unfortunately, the night sky is disappearing from view primarily because of “light pollution” that reduces the brightness of the stars and prevents the human eye from fully adapting to natural darkness. Outdoor lighting that is excessive, inefficient, and ineffective can produce light pollution that degrades the quality of natural darkness and the night sky by creating “sky glow.” Cinzano et al. (2001) estimated that more than 99% of the U.S. population (excluding Alaska and Hawaii) lives in areas that are light polluted and that two-thirds of Americans could no longer see the Milky Way from their homes.1 Light pollution is caused by increasing development, but may be more related to lighting that is oriented upward or sideways rather than down at the intended target. Light from urban areas can reduce the brightness of the night sky over 200 miles (322 km) away (https://www.nature.nps.gov/sound_night/; Smith and Hallo 2013).

1 This sentence was revised on 9 September 2015. See Erratum for further information.

National parks, especially those far from urban areas, are some of the last refuges of dark night skies, and the importance of night skies is increasingly reflected in National Park Service (NPS) policy and management. For example, Duriscoe (2001) argues that the night sky should be recognized as an important and increasingly scarce resource that must be managed and preserved, and that this is a natural extension of the NPS Organic Act (16 U.S.C. 1, 39 Stat. 535, 25 August 25 1916) as well at the Wilderness Act of 1964 (Public Law 88-577, 16 U.S.C. 1131-1136, 3 September 1964). Current NPS management policies include a requirement for managing “lightscapes,” or natural darkness and night skies (National Park Service 2006), and a relatively new administrative NPS unit, the Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division, was created to help carry out this responsibility. Night sky interpretive programs are now conducted in an increasing number of units of the National Park System, as manifested in night sky festivals and “star parties” at Yosemite (California), Acadia (Maine), and Death Valley (California) National Parks; creation of a night sky ranger position at Bryce Canyon National Park (Utah); and development of an observatory at Chaco Culture National Historical Park (New Mexico). The National Park Service established its Night Sky Team, a small group of scientists, in 1999 and this has led to rigorous measures of night sky quality and associated monitoring in the National Park System. Night sky quality is included as a “vital sign” by many of the 32 NPS Inventory and Monitoring Networks that cover the National Park System. The recent influential NPS report, “A Call to Action,” includes a recommendation that the National Park Service “lead the way in protecting natural darkness as a precious resource and create a model for dark sky protection” (National Park System Advisory Board 2012). A recent survey of managers across the National Park System found that night skies (and “night resources” more broadly, including the opportunity to observe nocturnal species) are frequently used by visitors and that managers are interested in identifying and managing night resources more actively (Smith and Hallo 2011).

Indicators and standards of quality for night sky viewing

Contemporary approaches to park and outdoor recreation management rely on a management-by-objectives approach as illustrated in figure 1 (Manning 2007; Whittaker et al. 2011; https://visitorusemanagement.nps.gov/). This management approach relies on formulation of indicators and standards of quality that serve as empirical measures of management objectives (such as protection of natural darkness). Indicators of quality are generally defined as measurable, manageable variables that are proxies for management objectives, while standards of quality (sometimes called “reference points” [Manning 2013] or “thresholds” [https://visitorusemanagement.nps.gov/]) define the minimum acceptable condition of indicator variables (Manning 2011; Whittaker et al. 2011; https://visitorusemanagement.nps.gov/). For example, a conventional indicator of quality for a wilderness experience is the number of groups encountered per day along trails, and a standard of quality is the maximum acceptable number of groups encountered, such as five. Once indicators and standards of quality have been formulated, indicator variables are monitored and management actions implemented to help ensure that standards of quality are maintained. This is an adaptive process that has been incorporated into NPS visitor use planning and management (https://visitorusemanagement.nps.gov/).

Formulation of indicators and standards of quality that address recreational use of parks can include engagement of park visitors. A growing body of research illustrates how this can be done through visitor surveys and associated theoretical and empirical approaches (Manning 2011). Several recent studies have concluded that there is a need for this type of research applied to night sky viewing or stargazing. For example, reflecting on their recent survey of park managers about nighttime recreation, Smith and Hallo (2013) conclude that “visitors must be polled about their perspectives of night recreation and night resources” (p. 58). In their evaluation of night sky interpretation at Bryce Canyon National Park and Cedar Breaks National Monument (Utah), Mace and McDaniel (2013) conclude that “additional research could lead to development of standards and indicators of quality for night skies in parks and protected areas, a perspective that has been very successful in the field of park and outdoor recreation management” (p. 55).

The study: Visitor surveys

NPS Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division

We conducted this study to help guide formulation of indicators and standards of quality for night sky viewing in the national parks. The program of research included two visitor surveys conducted at Acadia National Park (Acadia). Acadia is located primarily on Mount Desert Island, Maine. Many visitors stay overnight in one of the park’s two campgrounds, Blackwoods and Seawall. Because of its location away from large metropolitan areas, Acadia prides itself as a premier location to view the night sky in the eastern United States. The importance of the night sky at Acadia is manifested in the park’s annual Night Sky Festival, a four-day event featuring special presentations, activities, and star parties. Acadia’s regularly scheduled ranger programming also features night walks and astronomy evening programs.

The first survey addressed the importance of night sky viewing and associated indicators of quality. The survey instrument included two batteries of questions. The first addressed the importance of night sky viewing to park visitors by posing a series of statements (shown in table 1) and asking respondents to report the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each statement using a five-point response scale that ranged from −2 (“strongly disagree”) to 2 (“strongly agree”). The second battery of questions presented a series of items (shown in table 2) that visitors might see after dark in the park. The list included celestial bodies and human-caused sources of light. We asked respondents to report which items they did or did not see and indicate the extent to which seeing or not seeing these items added to or detracted from the quality of their experience in the park. A nine-point response scale that ranged from −4 (“substantially detracted”) to 4 (“substantially added”) was used. This latter battery of questions is adapted from a “listening exercise” that has been used to assess natural and human-caused sound in national parks and its effects on the quality of the visitor experience (Pilcher et al. 2009; Manning et al. 2010).

| Table 1. The importance of viewing the night sky to Acadia National Park visitors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Frequency of rating (%) | Mean | Standard Deviation | n | ||||

| Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||||

| −2 | −1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Viewing the night sky (stargazing) is important to me. | 0.0 | 1.0 | 9.4 | 35.4 | 54.2 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 192 |

| The National Park Service should work to protect the ability of visitors to see the night sky. | 0.0 | 1.1 | 8.9 | 36.8 | 53.2 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 190 |

| The National Park Service should conduct more programs to encourage visitors to view the night sky. | 0.5 | 2.1 | 27.1 | 37.5 | 32.8 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 192 |

| Acadia has a good reputation as a place to view the night sky. | 1.6 | 2.6 | 44.4 | 25.9 | 25.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 189 |

| One of the reasons I chose to visit Acadia is to view the night sky. | 4.2 | 12.1 | 39.5 | 26.3 | 17.9 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 190 |

| I would visit Acadia less often if it became more difficult to see the night sky. | 7.9 | 17.9 | 40.0 | 22.6 | 11.6 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 190 |

| Table 2. Questionnaire list of items seen and not seen at Acadia |

|---|

| The Milky Way |

| Constellations |

| Stars or planets |

| Meteors/shooting stars |

| The Moon |

| Satellites |

| Aircraft |

| Lights from distant cities |

| Lights from nearby towns |

| Campfires |

| Automobile lights |

| Flashlights |

| Lanterns |

| Streetlights |

| Portable work lights |

| Park building lights |

| Emergency vehicle lights |

We administered the survey to park visitors at the two campgrounds in Acadia. We sampled campground visitors because they were the most likely to be in the park at night (there are no other accommodations in the park). We intercepted groups of campers as they entered the campgrounds and gave a questionnaire to the group for a self-identified group leader to complete. We asked respondents to complete the questionnaire before they went to sleep that night or early the following morning, and then return the completed questionnaire to a drop box as they left the campground the next morning. We administered the survey for 13 days in August 2012. We contacted 277 groups and 273 agreed to participate; 194 completed questionnaires were returned representing a 70% response rate. The survey was administered under a grant to Clemson University by Musco Lighting and was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. In addition, a research permit was received from Acadia National Park.

The second survey addressed standards of quality for night sky viewing. We prepared a series of eight visual simulations of the night sky at Acadia as shown in figure 2. These simulations portrayed equally spaced degrees of light pollution. We asked respondents to rate the acceptability of each of the simulations using a seven-point response scale that ranged from −3 (“very unacceptable”) to 3 (“very acceptable”). We asked an additional suite of questions based on the series of visual simulations, as follows:

- Which image shows the night sky you would prefer to see in the park?

- Which image represents the maximum amount of human-caused light the National Park Service should allow in and around this park?2

- Which image is so unacceptable that you would no longer come to this park to stargaze or view the night sky?

- Which image is so unacceptable that you would not stargaze or view the night sky when visiting this park?

- Which image looks most like the night sky you typically saw in this park during this trip?

- Which image looks most like the night sky you think is “natural” in this park?

- Which image looks most like the night sky you typically see from your home?

2 The National Park Service can help control light generated within parks through design and installation of park lighting, and can work with surrounding communities to help manage light generated outside parks.

We administered the survey to park visitors at seven attraction sites in Acadia. Visitors were sampled if they had spent at least one night on Mount Desert Island in the vicinity of the park. We intercepted visitors as they entered the attraction sites and gave a questionnaire to the group for a self-identified group leader to complete. We instructed respondents to complete the questionnaire at that time and return it to the survey attendant stationed there. The survey attendant answered any questions respondents had about the questionnaire. We administered the survey for nine days in August and September 2013. We contacted 274 groups and 137 visitors agreed to participate and completed questionnaires representing a 50% response rate. Because this study was funded by the National Park Service, the survey was submitted for approval by the federal Office of Management and Budget under the NPS expedited approval process. A research permit was also received from Acadia National Park.

Surveying visitors about the night sky can be challenging. One of the survey objectives was to ensure that survey participants had spent time in or just outside the park at least one night to help make certain they had had an opportunity to view the park’s night sky. A pilot test recruited visitors at the park’s evening campfire programs, but few visitors were willing to participate at this late hour. The two other sampling approaches described earlier were more successful in reaching the target population while attaining an acceptable response rate. Another challenging issue is determining the night sky conditions that respondents experienced, since these conditions can be highly varied and transitory. In this study, we asked respondents to report the study photograph that was most like the conditions they typically experienced in the park.

Visual research methods are an effective approach to measuring standards of quality for parks and related areas (Manning and Freimund, 2004; Manning 2007). For example, visually based studies can be especially useful for studying standards of quality for indicator variables that are inherently difficult or awkward to describe in conventional narrative/numerical terms, such as trail erosion. A visual approach has been used to study a wide variety of indicators of quality, including crowding, conflict, resource impacts, and management practices (Manning 2011). Several studies have addressed multiple dimensions of the validity of visual research methods, and findings are generally supportive (Manning 2007). However, findings are mixed on the issue of the order in which study photographs should be presented to respondents and the range of potential standards of quality presented (Manning 2011; Gibson et al. 2014). This study addresses these issues by presenting study photographs on posters, allowing respondents to see all photos at the same time (rather than one at a time), and presenting a complete range of night sky conditions from pristine to severely light polluted (see figure 2, above and in photo gallery at top of page).

Study findings

Importance of night skies

Findings from the battery of questions addressing the importance of night sky viewing are shown in table 1 and indicate that the vast majority of visitors feel that (1) night sky viewing is important, (2) the National Park Service should protect opportunities for visitors to see the night sky, and (3) the Service should conduct more programs to encourage visitors to view the night sky. Most visitors also reported that Acadia has a good reputation for night sky viewing and that this is one of the reasons they chose to visit Acadia. However, feelings were mixed as to whether respondents would visit Acadia less if it became more difficult to see the night sky (40% reported that they were unsure about this).

Indicators of quality for night sky viewing

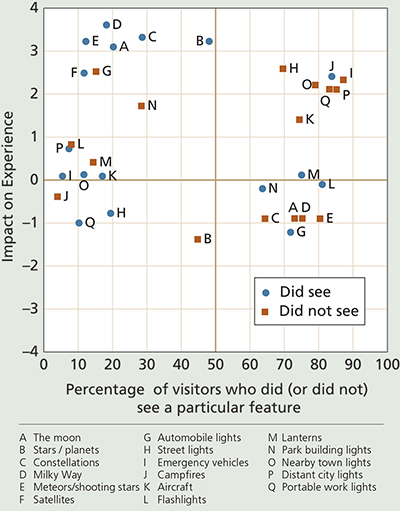

Findings from the battery of questions addressing indicators of quality for night sky viewing are presented in the form of an importance-performance framework as shown in figure 3. Importance-performance analysis is a way to evaluate visitor desires and associated experiences and has been used to identify indicators of quality in a range of park and outdoor recreation settings and for several recreation activities (Guadagnolo 1985; Mengak et al. 1986; Hollenhorst and Stull-Gardner 1992; Hollenhorst et al. 1992; Hunt et al. 2003; Pilcher et al. 2009). For example, importance-performance analysis was used to identify indicators of quality for natural quiet in national parks (Pilcher et al. 2009). Similarly, a study of visitor experiences in wilderness used importance-performance analysis to reveal indicators of quality for resource and experiential conditions on trails and in campgrounds (Hollenhorst and Gardner 1994).

Figure 3 graphs the percentage of visitors who did or did not see the items listed in table 2; (x-axis) and how seeing or not seeing these items affected the quality of visitors’ experiences (y-axis). Generally, the graph shows that most visitors did not see many of the celestial objects included in the questionnaire, but that when they did, it substantially added to the quality of their experience. Likewise, most visitors did not see many of the sources of human-caused light and this also substantially added to the quality of their experience. Campfires are an exception to these generalizations: most visitors saw campfires and this added to the quality of their experience. Overall, the findings suggest that the brightness of celestial bodies and, therefore, light pollution is an important indicator of quality at Acadia.

Standards of quality for night sky viewing

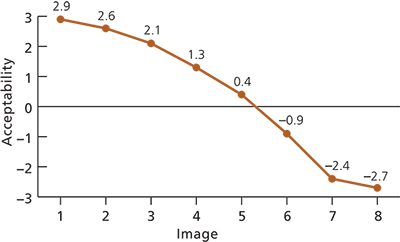

Findings from the questions addressing standards of quality for night sky viewing as manifested in the brightness of celestial objects (or alternatively, the amount of light pollution) are shown in figure 4 and table 3. The graph in figure 4 is derived from the average (mean) acceptability ratings for each of the eight visual simulations. This type of graph has been used to help formulate standards of quality for resource and experiential conditions in a number of national parks (Manning et al. 1996; Shelby et al. 1996; Freimund et al. 2002; Hsu et al. 2007). It is clear from the graph that increasing amounts of light pollution are increasingly unacceptable. Average acceptability ratings fall out of the acceptable range and into the unacceptable range at around image 5 in the series presented in figure 2, and this represents a potential standard of quality (defined earlier as the minimum acceptable condition of an indicator of quality). However, the data in table 3 suggest a range of other potential standards of quality. For example, Acadia managers have identified night skies as an especially important resource and this suggests that a higher standard of quality—closer to what visitors feel is the maximum amount of human-caused light the NPS should allow (between images three and four in figure 2)—may be appropriate.

| Table 3. Alternative standards of quality of night sky viewing | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study Question | Image Number | Standard Deviation |

| The point at which the social norm curve crosses the neutral point of the acceptability scale (from fig. 4) | 5.2 | — |

| Which image shows the night sky you would prefer to see? | 1.1 | 0.4 |

| Which image shows the maximum amount of human-caused light the National Park Service should allow? | 3.7 | 1.8 |

| Which image is so unacceptable that you would no longer come to this park to view the night sky? | 6.1 | 1.4 |

| Which image is so unacceptable that you would no longer view the night sky when visiting this park? | 6.1 | 1.4 |

| Which image looks most like the night sky you typically saw in this park during this trip? | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| Which image looks most like the night sky you think is “natural” at this park? | 2.0 | 1.2 |

| Which image looks most like the night sky you typically see from your home? | 4.9 | 2.1 |

Conclusion

Night skies are increasingly recognized as an important resource—biologically, culturally, and experientially—in the national parks, and this is reflected in recent NPS policy and management. This study documents this importance to national park visitors. The importance of night skies will require more explicit management in the national parks, including formulating indicators and standards of quality for viewing the night sky. The program of research described in this article suggests how park visitors and other stakeholders can be engaged in this process. Findings from this study suggest the amount of light pollution is a good indicator of quality for management of night skies, and that standards of quality range from approximately study photo 1 (the condition visitors would prefer) to approximately photo 6 (the condition at which visitors would no longer stargaze [table 3]).Of course this study applies specifically to Acadia, but it could be replicated in other parks or regions.

As described earlier and illustrated in figure 1, management of night skies will also require monitoring the brightness of celestial bodies and the amount of light pollution, as well actions designed to maintain standards of quality by controlling light pollution in and around national parks. The NPS Night Skies Team is engaged in a program of monitoring the condition of night skies in the National Park System (Albers and Duriscoe 2001; Moore 2001). However, controlling light pollution is likely to be more challenging. Of course, the National Park Service can and should adopt best lighting practices designed to minimize light pollution within national parks (Chan and Clark 2001). But controlling light pollution outside park boundaries will require a proactive approach of working with surrounding communities. Acadia offers a good example of this approach, working with the gateway town of Bar Harbor, which recently adopted a new lighting ordinance for the town designed to encourage efficiency and reduce light pollution (Maine Association of Conservation Commissions 2010). Chaco Culture National Historical Park offers another good example, working with stakeholder groups successfully to encourage the state legislature to pass the New Mexico Night Sky Protection Act, regulating outdoor lighting throughout the state (Rogers and Sovick 2001b; Manning and Anderson 2012).

Controlling light pollution in and around national parks might further be promoted by “astronomical tourism” (Bemus 2001; Collison and Poe 2013). Paradoxically, as the opportunity for high-quality stargazing has diminished, its value may be increasing. In this way, the economic benefits of tourism based on stargazing (and other elements of natural darkness) may encourage communities in and around national parks to help reduce light pollution.

Fortunately, natural darkness, particularly the night sky, is a renewable resource; light pollution is largely transitory in both space and time. Though light pollution may have already had irreversible biological and ecological impacts, it can be controlled and even reduced, thus restoring the brightness of the night sky. The national parks, with their emphasis on protection of natural and cultural resources and the quality of visitor experiences, are a good place to advance this cause.

References

Albers, S., and D. Duriscoe. 2001. Modeling light pollution from population data and implications for National Park Service lands. The George Wright Forum 18:56–68.

Alvarez del Castillo, E. M., D. L. Crawford, and D. R. Davis. 2003. Preserving our nighttime environment: A global approach. Pages 49–67 in Hugo E. Schwarz, editor. Light pollution: The global view (Astrophysics and Space Science Library, volume 284). Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

Bemus, T. 2001. Stargazing: A driving force in ecotourism at Cherry Springs State Park. The George Wright Forum 18:69–71.

Bogard, P. 2013. The end of night: Searching for natural darkness in an age of artificial light. Little, Brown, and Company; New York, New York, USA.

Chan, L., and E. Clark. 2001. Yellowstone by night. The George Wright Forum 18:83-86.

Chepesiuk, R. 2009. Missing the dark: Health effects of light pollution. Environmental Health Perspectives 117(1):A20-A27.

Cinzano, P., F. Falchi, and C. D. Elvidge. 2001. The first world atlas of the artificial night sky brightness. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 328:689–707.3

3 This reference was revised on 9 September 2015. See Erratum for further information.

Clark, B. A. J. 2006. A rationale for the mandatory limitation of outdoor lighting. Astronomical Society of Victoria, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Available at http://unihedron.com/projects/darksky/lp181c.pdf.

Collison, F. M., and K. Poe. 2013. Astronomical tourism: The astronomy and dark sky program at Bryce Canyon National Park. Tourism Management Perspectives 7:1–15.

Duriscoe, D. 2001. Preserving pristine night skies in national parks and the wilderness ethic. The George Wright Forum 18:30–36.

Freimund, W. A., J. J. Vaske, M. P. Donnelly, and T. A. Miller. 2002. Using video surveys to access dispersed backcountry visitors’ norms. Leisure Sciences 24 (3–4):349–362.

Guadagnolo, F. 1985. The importance-performance analysis: An evaluation and marketing tool. Journal of Parks and Recreation 2:13–22.

Hollenhorst, S., D. Olson, and R. Fortney. 1992. Use of importance-performance analysis to evaluate state park cabins: The case of the West Virginia State Park System. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 10:1–11.

Hollenhorst, S., and L. Gardner. 1994. The indicator performance estimate approach to determining acceptable wilderness conditions. Environmental Management 18(6): 901–906.

Hollenhorst, S., and L. Stull-Gardner. 1992. The indicator-performance estimate (IPE) approach to defining acceptable conditions in wilderness. Pages 48–49 in D. J. Chavez, technical coordinator. Proceedings of the Symposium on Social Aspects and Recreation Research, 19–22 February 1992, Ontario, California. General Technical Report PSW-132, USDA Forest Service, Albany, California, USA. Available at https://www.fs.fed.us/psw/publications/documents/psw_gtr132/psw_gtr132_02_hollenhorst.pdf.

Hsu, Y., C. Li, and O. Chuang. 2007. Encounters, norms and perceived crowding of hikers in a non-North American backcountry recreational context. Forest, Snow, and Landscape Research 81(1-2):99–108.

Hunt, K., D. Scott, and S. Richardson. 2003. Positioning public recreation and park offerings using importance-performance analysis. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 21(3):1–21.

Lima, S. L. 1998. Stress and decision-making under the risk of predation: recent developments from behavioral, reproductive and ecological perspectives. Advanced Studies in Behavior 27:215–290.

Longcore, T., and C. Rich. 2004. Ecological light pollution. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2(4):191–198.

López, J. M. G., and J. D.-R. Suárez. 2007. The right to starlight, another step towards controlling pollution and efficient use of natural resources. Pages 267–273 in M. Cipriano and J. Jafari, editors. Starlight: A Common Heritage proceedings. Available at http://www.starlight2007.net/pdf/StralightCommonHeritage.pdf.

Luginbuhl, C. B., C. E. Walker, and R. J. Wainscoat. 2009. Lighting and astronomy. Physics Today 62(12):32–37.

Mace, B. L., and J. McDaniel. 2013. Visitor evaluation of night sky interpretation in Bryce Canyon National Park and Cedar Breaks National Monument. Journal of Interpretation 18(1):39–57. Available at http://www.interpnet.com/docs/JIR-v18n1.pdf.

Maine Association of Conservation Commissions. 2010. Bar Harbor’s dark skies ordinance, Bar Harbor, Maine. Home rules, home tools: Locally led conservation achievements. Summer:1–2. Available at http://www.meacc.net/achievements/Bar%20Harbor%20case%20study.pdf.

Manning, R. 2007. Parks and carrying capacity: Commons without tragedy. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

———. 2011. Studies in outdoor recreation: Search and research for satisfaction. Third edition. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

———. 2013. Social norms and reference points: Integrating sociology and ecology. Environmental Conservation 40(4):310–317.

Manning, R. E., and L. E. Anderson. 2012. Managing outdoor recreation: Case studies in the national parks. CABI, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

Manning, R. E., and W. Freimund. 2004. Use of visual research methods to measure standards of quality for parks and outdoor recreation. Journal of Leisure Research 36(4):557–579.

Manning, R. E., W. A. Freimund, D. W. Lime, and D. G. Pitt. 1996. Crowding norms at frontcountry sites: A visual approach to setting standards of quality. Leisure Sciences 18(1):39–59.

Manning, R., P. Newman, K. Fristrup, D. Stack, and E. Pilcher. 2010. A program of research to support management of visitor-caused noise at Muir Woods National Monument. Park Science 26(3):54–58.

Mengak, K., F, Dottavio, and J. O’Leary. 1986. Use of importance-performance analysis to evaluate a visitor center. Journal of Interpretation 11(2):1–13.

Moore, C. A. 2001. Visual estimations of night sky brightness. The George Wright Forum 18:46–55.

National Park System Advisory Board. 2012. A call to action: Preparing for a second century of stewardship and engagement. National Park Service, Washington, D.C., USA. Available at https://www.nps.gov/calltoaction/.

National Park Service. 2006. Management policies 2006. Accessed 9 September 2014 from https://www.nps.gov/policy/mp2006.pdf.

Navara, K. J., and R. J. Nelson. 2007. The dark side of light at night: Physiological, epidemiological, and ecological consequences. Journal of Pineal Research 43(3):215–224. Abstract available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17803517.

Nicholas, M. 2001. Light pollution and marine turtle hatchlings: The straw that breaks the camel’s back? The George Wright Forum 18:77–82.

Pauley, S. 2004. Lighting for the human circadian clock: Recent research indicates that lighting has become a public health issue. Medical Hypotheses 63:588–596.

Perry, G., and R. N. Fisher. 2006. Night lights and reptiles: Observed and potential effects. Pages 169–191 in C. Rich and T. Longcore, editors. Ecological consequences of artificial night lighting. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

Pilcher, E. J., P. Newman, and R. E. Manning. 2009. Understanding and managing experiential aspects of soundscapes at Muir Woods National Monument. Environmental Management 43(3):425–435.

Rich, C., and T. Longcore. 2006. Ecological consequences of artificial night lighting. Island Press, Washington D.C., USA.

Rogers, J., and J. Sovick. 2001a. The ultimate cultural resource? The George Wright Forum 18:25–29.

———. 2001b. Let there be dark: The National Park Service and the New Mexico Night Sky Protection Act. The George Wright Forum 18:37–45.

Shelby, B., J. J. Vaske, and M. P. Donnelly. 1996. Norms, standards, and natural resources. Leisure Sciences 18(2):103–123.

Smith, B., and J. Hallo. 2011. National Park Service unit managers’ perceptions, priorities, and strategies of night as a unit resource. Presentation, George Wright Society Conference, 14–18 March, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA.

Smith, B. L., and J. C. Hallo. 2013. A system-wide assessment of night resources and night recreation in the U.S. national parks: A case for expanded definitions. Park Science 29(2):54–59.

Whittaker, D., B. Shelby, R. Manning, D. Cole, and G. Haas. 2011. Capacity reconsidered: Finding consensus and clarifying differences. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 29(1):1–20.

Wise, S. E., and B. W. Buchanan. 2006. The influence of artificial illumination on the nocturnal behavior and physiology of salamanders: Studies in the laboratory and field. Pages 221–251 in C. Rich and T. Longcore, editors. Ecological consequences of artificial night lighting. Island Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

Witherington, B. E., and R. E. Martin. 2000. Understanding, assessing, and resolving light-pollution problems on sea turtle nesting beaches. Technical Report TR-2. Florida Marine Research Institute, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, Melbourne, Florida, USA.

About the authors

Robert Manning is professor and director of the Park Studies Laboratory at the University of Vermont. He can be reached by e-mail. Ellen Rovelstad was a graduate research assistant in the Park Studies Laboratory at the time these studies were conducted. Chadwick Moore was with the National Park Service Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division in Fort Collins, Colorado. Jeffrey Hallo is an associate professor in the Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism Management at Clemson University. Brandi Smith is a graduate student and Good Lighting Practices Fellow at Clemson University.

Erratum

On 8 September 2015 a reader called our attention to two errors in this research report, which had been published four days earlier. The first half of the third sentence in the third paragraph was incorrect and read, “By 2000, it was estimated that 99% of the world’s skies were light polluted …” The citation, given as “Cinzano, P., F. Falchi, and C. D. Elvidge. 2001. Naked-eye star visibility and limiting magnitude mapped from DMSP-OLS satellite data. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 323:34–46,” was also wrong. The sentence and reference have been corrected and are indicated as such in the text (9 September 2015).

Download: PDF of print version of article

This article published

Online: 4 September 2015; In print: 25 March 2016

URL

https://www.nps.gov/ParkScience/articles/articles/parkscience32_1_32_2_manning_et_al_3826_3831.htm

Suggested citation (print)

Manning, R., E. Rovelstad, C. Moore, J. Hallo, and B. Smith. 2016. Indicators and standards of quality for viewing the night sky in the national parks. Park Science 32(2):9–17.

Suggested citation (advance online)

Manning, R., E. Rovelstad, C. Moore, J. Hallo, and B. Smith. 2015. Indicators and standards of quality for viewing the night sky in the national parks. Park Science 32(1). Advance online publication.

This page updated

5 May 2016

Site navigation

• Back to Volume 32, Number 2

• Back to Volume 32, Number 1

• Back to Park Science home page

Last updated: August 9, 2018