Last updated: August 9, 2019

Article

Missouri and the 19th Amendment

CC0

Women first organized and collectively fought for suffrage at the national level in July of 1848. Suffragists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott convened a meeting of over 300 people in Seneca Falls, New York. In the following decades, women marched, protested, lobbied, and even went to jail. By the 1870s, women pressured Congress to vote on an amendment that would recognize their suffrage rights. This amendment was sometimes known as the Susan B. Anthony Amendment and became the 19th Amendment.

The amendment reads:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex."

Although progress on the federal amendment stalled, women also campaigned for changes to state suffrage requirements to win the vote. Missouri women began forming suffrage organizations in 1867. Between 1867 and 1901, suffragists petitioned for a state constitutional amendment enfranchising women eighteen times. Only eight of those petitions came to a vote in the Missouri legislature, including the first one in 1867. Each time, the Missouri lawmakers voted against woman suffrage.

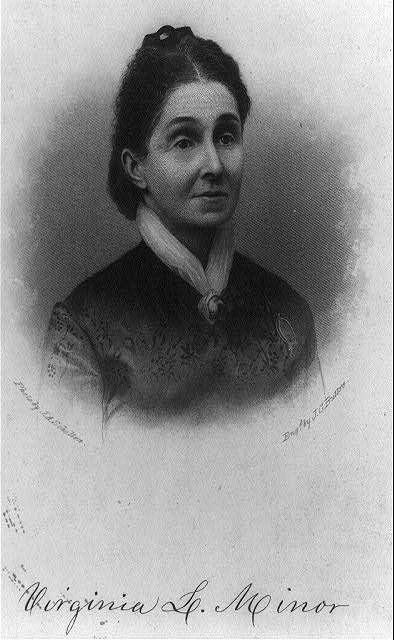

In October 1869, St. Louis hosted a National Woman Suffrage Convention. At the meeting, Missourians Francis and Virginia Minor introduced the idea that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution already protected women’s right to vote. They argued that since the language of the amendment defined citizenship and required due process and equal protection for all citizens under the law, it was unconstitutional to exclude women citizens from voting. Support for the Minors’ argument grew among suffragists, launching a strategy known as the “new departure” in which women showed up at their polling places demanding that they be allowed to vote.

Library of Congress

Missouri Historical Society Collections

Three months later, after decades of arguments for and against women's suffrage, Congress finally passed the federal suffrage amendment on June 4, 1919. After Congress approved the 19th Amendment, at least 36 states needed to vote in favor of it for it to become part of the U.S. Constitution. This process is called ratification.

On July 3, 1919, Missouri ratified the Nineteenth Amendment. By August of 1920, 36 states had ratified the amendment, ensuring that citizens could not be denied the right to vote based on sex.

This photograph was taken in 1919 when Missouri Governor Frederick Gardner signed a resolution ratifying the 19th Amendment to U.S. Constitution. Missouri became the 11th state to ratify the amendment.

Library of Congress, Lot 5543 https://www.loc.gov/item/2003668342/

Missouri Places of Women's Suffrage:

Railway Exchange Building

Built in 1914, the Railway Exchange Building in St. Louis is a high-rise office building. It was once the headquarters of a local women’s suffrage organization in the years leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment. The building is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is privately owned and closed to the public.

The Railway Exchange Building is an important place in the story of ratification. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.