Part of a series of articles titled Democracy Limited: The Suffrage "Prison Special" Tour of 1919.

Previous: Democracy Limited: The Politics of Dress

Article

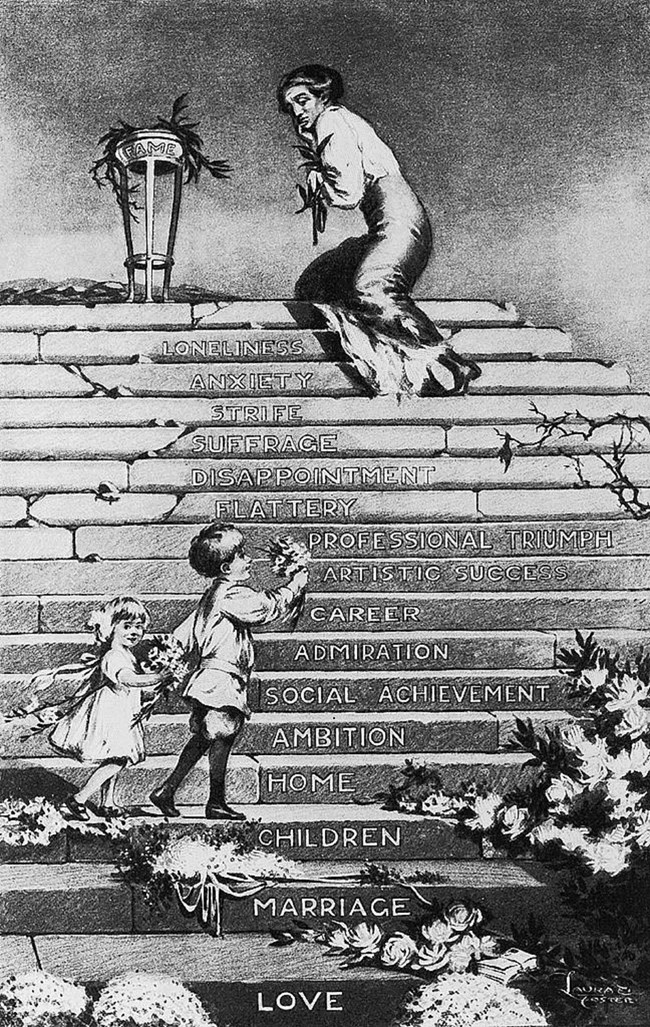

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2002716765/).

“Nay, be not alarmed. They are perfectly gentle, lovable, delightful women more or less known throughout the nation by reason of their social position and prominence of their families in the money marts of the world, yet who, nevertheless, wear upon their breasts the badge of the prison gate with its dangling chain.” —Oakland Tribune, January 30, 1919, on the Prison Special

Respectability is a set of social guidelines dictating acceptable behavior, from clothing to the way someone interacts with those around them. “Respectability politics” refers to the way that people attempting to make social change present their demands in a way that are acceptable to the dominant standards in their society.

During the suffrage movement of the early twentieth century, women argued for increased political rights for themselves to a government run by men with little incentive to agree. Cartoons and caricatures in the press at the time demonstrate the ways in which women were mocked and dismissed for stepping out of their traditional role as wives and mothers. Women had to show that what they were fighting for was respectable for women.

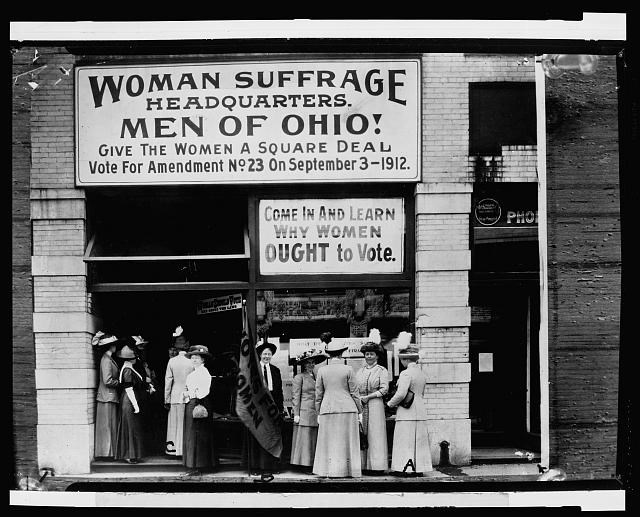

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/97500065).

The question of respectability affected the suffragists in ways that made many feel out of place in the movement. Part of the conflict between the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the largest suffrage organization under Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Carrie Chapman Catt, and Alice Paul and Lucy Burns’ National Woman’s Party (NWP) was disagreement over how best to frame their cause. Stanton and Catt were sure that the best way to gain support for women’s right to vote was through careful fundraising and influential members. This meant recruiting women who could convince their rich fathers and political husbands to join the effort for women’s suffrage. All of these women were white. The attention-getting tactics the NWP proposed were rejected as violation of the reserved way in which society expected women to act. The violence that occurred at the 1913 Suffrage Procession demonstrated why it was so dangerous to violate society’s rules.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/93505051).

The suffragists who followed Alice Paul and risked their freedom and life for the cause also struggled with presenting themselves in a “respectable” way. The NWP invited women from different social classes to join and work with their organization. Rallying women who worked was one of their key strategies to gaining much needed numbers. The NWP continued to fail in building a multiracial movement for women’s suffrage, however. The Suffrage Procession of 1913 demonstrated underlying racism in the white women’s suffrage movement. Organized and led by the forward-thinking Alice Paul, it was intended to be a demonstration of unity in protest of the exclusion of women from the country’s government. Yet the NWP initially attempted to exclude black women from the parade and even after conceding, told Black women suffragists that they must march in the back of the procession. Often excluded from NAWSA and the NWP, Black women suffragists often formed their own organizations where they would not have to face racism from white women activists. Paul and others believed that marginalizing Black women would make their cause palatable and respectable to white Southerners who were opposed to suffrage rights for Black Americans. The mainstream suffrage movement’s dismissal of Black women’s voting rights damaged the movement’s claim that they were fighting for all women. Many Black women, particularly in the South, would not gain full voting rights until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

These ideas about respectability also affected the Prison Special tour. The 26 women chosen to represent the suffragists who had been imprisoned and abused had identities that would get the most sympathy from influential male politicians. Some were wives and mothers, sisters of politicians, and granddaughters of Founding Fathers. These were the women who were already highly regarded and treated better than other women. Tales of imprisonment and abuse from poor white women and women of color would have been less shocking to the suffragists’ target audience. The significance of the Prison Special specifically was that respectable women were treated so poorly.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b23344).

The presentation of such women as abused criminals was outrageous to many who attended the tour. Society said that these privileged women had sensitive natures and should be kept safe. Anti-suffragists often argued that politics were too dirty for women and that men needed to protect them. Yet these suffragists’ accounts of their time in prison showed that they had dealt with literal filth as they scrubbed toilets and lived with unsatisfactory hygienic facilities. They had lived with incarcerated individuals whom respectable society considered “dirty.” And it was the men and the state, meant to protect the women, who put them into that situation.

What the suffragists described only had the impact it did because of who was speaking. Alice Paul and the suffragists she led leveraged their societal “respectability” for the cause of women’s suffrage. At the same time, wealthy white suffragists’ use of respectability politics meant that they neglected populations of women, particularly Black and Native American women. They justified their exclusion with the idea once women could vote they would be able to address the issues of women who had been left out. Yet it took decades more for the promise of the 19th Amendment to be realized.

Palczewski, Catherine H. "The 1919 Prison Special: Constituting White Women's Citizenship." Quarterly Journal of Speech 102:2, 107-132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2016.1154185.

Paul, Alice. "Conversations with Alice Paul: Woman Suffrage and the Equal Rights Amendment. Interview by Amelia R. Fry. University of California, 1976. http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt6f59n89c&query=&brand=calisphere.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. New York: Boni & Liveright, 1920.

by Brianna Nuñez-Franklin

Part of a series of articles titled Democracy Limited: The Suffrage "Prison Special" Tour of 1919.

Previous: Democracy Limited: The Politics of Dress

Last updated: November 14, 2023