NPS Photo

Abandoned Mine Lands (also referred to as Abandoned Mineral Lands, or AMLs) are disturbed lands altered by the operations conducted in search of minerals at surface and underground sites. AMLs include sites and features associated with hard-rock, placer, and dredge mining; gravel pits, rock quarries, oil and gas exploration and development; and geothermal sites.

The wide variety of mining processes employed in search of valuable mineral commodities has made for fascinating study in the 49th state. From the Klondike Gold Rush that spread to the Yukon, to more recent gold discoveries, such as the beach placers of the Nome coast, evidence of mining is found throughout the history of the state and the Alaskan parks.

NPS Photo

In the far north, placer mining of permafrost and hard rock mining resulted in a scattering of abandoned mine features that have deteriorated in the harsh climate, leaving many naturally reclaimed. In Denali, the Kantishna mining district comprises dozens of mining efforts representing various eras and stages of mining operations, both from hard rock and placer mining techniques.

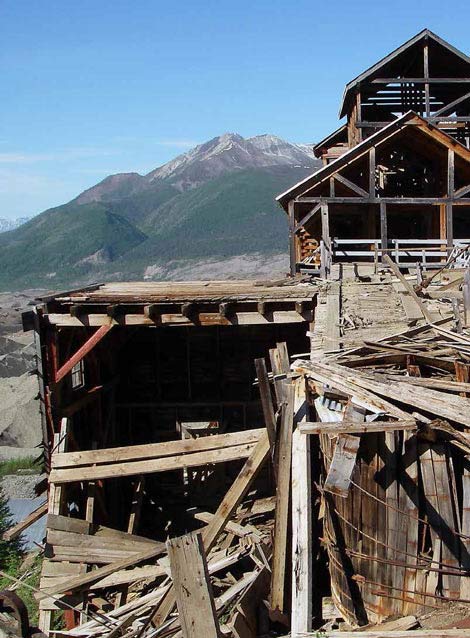

Hard rock mines are abundant in the mountains of Wrangell-St. Elias, with recognizable features that are found in many other parts of the country. Beach placer deposits have been staked along Alaska’s extensive coastline in several episodes of frantic activity. Interior Alaska saw both placer and hard rock mines for metals and coal. The large bucket-line dredges that once plied the frozen ground of numerous drainages of the Yukon River country are representative of the industrious nature and fortitude of the Alaskan miner. These sites represent the mystique and lore of the hardy individualists that explored and settled the Alaskan wilderness, and provide visitors with a tangible connection to the heritage preserved by these sites.

These sites also preserve many safety and environmental hazards that visitors unfamiliar with mining operations may not recognize as hazards. Examples of these hazards are numerous and include crumbling structures, failing portals, open shafts, and structures clinging precariously to cliffs that represent extreme falling hazards.

NPS Photo

The remote location of these features intensifies the seriousness of injury that can occur at these sites, which are often the intended destination in a region of roadless wilderness. Additionally, as part of the history of Alaskan settlement, many sites have interpretive displays or information for park visitors, highlighting the interest in these features.

From the thousands of mining claims that existed at the time of the establishment of the Alaska park units, several hundred still remain within park units, leaving many abandoned sites and features in various stages of disrepair and failure scattered throughout the parks. There are approximately 750 of these abandoned mine features on National Park Service (NPS) lands in Alaska.

NPS Photo

Initial AML Program Efforts

Since 1981, the NPS Alaska region management has worked to quantify the number and type of hazards posed by these sites and has pursued a variety of solutions to mitigate the issues presented by relic mining features. Initial efforts beginning in the late 1980s, in partnership with the State of Alaska AML Program, and the Office of Surface Mining, instituted closure of a number of mine entrances utilizing polyurethane foam methodologies, and the installation of lightweight steel gates.

Following these efforts to mitigate the most serious immediate safety hazards, beginning in 1991, and continuing through 2010, agency staff identified mining-impacted landscapes for restoration projects that resulted in large-scale mitigation and reclamation of the effects of mining and associated mine workings. Numerous drainages in Denali, Gates of the Arctic, Yukon-Charley Rivers, and Wrangell-St. Elias parks were part of a multi-year effort to remove mining debris, including thousands of empty fuel drums and non-historic trash.

NPS Photo

Landscape restoration activities at Kantishna in Denali (Adema et al. 2011), and the soils mitigation project at Coal Creek in Yukon-Charley Rivers (Stromquist 2005) are examples of reclamation projects undertaken by NPS during this time period.

These projects restored altered riparian zones by re-establishing natural drainage patterns and vegetation, and mitigating contaminated soils associated with past mining activities.

ARRA Funding: the Next AML Phase

NPS AML management received a boost when congressional set asides through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) in 2009 and 2010 provided funding for the mitigation of known high-risk physical safety hazards at mine sites service-wide, the direct result of a Department of Interior audit of management of AMLs.

With these funds, Alaska region program managers aggressively tackled a backlog of known safety issues and mitigated hazards at numerous locations throughout the Alaska parks.

NPS Photo

In Alaska, a large component, and the highest priority, of AML hazards removal has been abandoned explosives mitigation. Abandoned explosives include blasting caps, dynamite, explosive materials, and blasting fuse and cord, all which have been found at many AML sites throughout the parks. Removing or neutralizing explosives was carefully conducted by NPS staff, as the Alaska region was fortunate to have a trained and certified blasting officer for many years.

These hazards were safely disposed of prior to additional inventory and assessment work by park staff. To date, the NPS has safely mitigated 2,188 blasting caps, 3,653 pounds (1,657 kilograms) of dynamite, and 9,805 feet (2,989 meters) of blasting fuse from sites throughout the region.

NPS Photo

In addressing other sites on the backlog list, and prior to initiating mitigation and closure, site visits were required to inventory the entire mine site and record feature-specific measurements.

The sites were also surveyed for cultural resources documentation and determination of historic value. These data informed project compliance and formulation of project plans and logistics.

NPS Photo

Selection of closure type must consider accessibility, stability of the feature, the geologic conditions on-site, necessity to maintain water or air flow, wildlife concerns, cultural resource preservation, and numerous other site aspects. The site-specific data were used to adaptively design closures for sites with clearly identified hazards utilizing proven technologies. The most common mitigation and closure techniques that have been employed at Alaska sites include:

- Warning signs illustrating hazards at abandoned mine sites and prohibiting access. Signs are frequently the first response measure prior to more permanent closure methods.

- In some locations, where natural deterioration and partial failure of the mine opening has occurred, the collapse and closure has been facilitated by staff using hand tools and controlled blasting.

- Polyurethane foam (PUF) plugs with a surface cap of native materials have been one of the more frequently employed closure mechanisms in the Alaska park units. PUF compo-nents can be transported relatively easily to remote sites, where combined, the foam expands up to 30 times its original volume and sets up quickly, even in the cooler temperatures of many mine sites in Alaska. Foam plugs are used when site conditions at the portal or opening are not stable, or competent, and there is no reason to maintain access.

- Steel gate closures (often made of manganol) may be installed with lock mechanisms to allow access. Steel gate closures are used in situations where the portal walls are stable and competent, allowing installation of rock anchors to which gate components are welded. Gates are used to allow for interpretive purposes and monitoring and sampling of the site, as well as to provide for wildlife passage, such as bats and small mammals.

NPS Photo

Once installed, all closures must be routinely monitored for damage caused by wildlife, vandalism, corrosion or failure of materials, and natural processes such as subsidence and weathering.

AML Inventory Project

NPS managers recognized that the ARRA funds were insufficient to deal with the magnitude of the AML issue on NPS lands. As the ARRA projects neared completion, a new service-wide inventory effort was established. The goal of this project was the systematic and comprehensive inventory and assessment of all AMLs on National Park Service lands, to identify site-specific human health and safety hazards associated with AML features, and to prioritize and create cost estimates for mitigation of these issues.

The timeframe for the ambitious project was 2010-2012. Research and fieldwork to accomplish the goals of the project began in October of 2010, following completion of the ARRA projects. Mine sites and features in parks were researched online through mining records and through park reporting methods. These sites were compiled and assessed for hazards, stability, and future mitigation requirements. Site visits were prioritized in alignment with previous AML program procedures, which identified as the highest priority those sites reported to have abandoned explosives, followed by sites with known or suspected open underground workings, or hazardous materials such as chemicals or petroleum products.

The limited timeframe with respect to the scope and schedule of this project necessitated access to several sites through the use of helicopter-based operations. Many locations in Glacier Bay National Park and Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve were accessed through boat-supported operations. Logistical support costs for these efforts were a large portion of the overall project expense.

NPS Photo

In Alaska, this comprehensive inventory was conducted by specifically trained NPS staff from the regional office in conjunction with resource specialists at the parks. Due to the expense of returning to these remote sites, NPS staff ensured that newly discovered safety threats such as explosives and obvious physical hazards were secured while the inventory team was onsite.

Numerous sites surveyed during the course of this project represented the first site visits by NPS employees in decades and provided information for eligibility determinations to the National Register of Historic Places. The inventory of the Alaska park units resulted in capturing data and documenting the status of 751 sites. Final data was reported to the AML database in December 2012.

With the information in hand from the conclusion of the comprehensive inventory, NPS management now has a clear understanding of the magnitude and scope of AML issues in the service. At this time, 54 of the most hazardous and easily accessed openings into abandoned mines in the Alaska parks have been physically closed to visitor access. Although no injuries or fatalities are known to have occurred at abandoned mine sites managed by the NPS in Alaska, many Alaska sites are near airstrips developed to support past mining activities. Those airstrips are frequently used now as backcountry drop-off points for hikers and visitors eager for remote wilderness experiences. The simple fact that the only access through a wilderness area may be along the vestiges of a 100-year-old road leading directly into abandoned mine workings weakens any suggestions that such sites pose less danger because they are so remote. While sheer remoteness could reduce the frequency of potentially hazardous encounters, the probability of delayed medical response means that injuries occurring in remote locations are more likely to become life- or limb-threatening.

Current Status of AMLs

Approximately 28 features in the Alaska park units were identified as high priority for mitigation by the recent inventory conducted for the NPS comprehensive AML report (Burghardt et al. 2013). The continued focus of AML program managers will be to resolve safety issues at these sites, ensure that mining-impacted landscapes are reclaimed to restore natural processes, and to preserve cultural resources and wildlife habitat. These abandoned features provide an opportunity to promote thoughtful perspectives of mining artifacts by informing and educating park visitors not only of the hazards, but also the significance and place in the landscape of our mining history.

NPS Photo

References

Adema, G., T. Brabets, J. Brekken, K. Karle, and B. Ourso. 2011.

Reclamation of Mined Lands in Kantishna, Denali National Park and Preserve. Alaska Park Science, Vol. 10, Issue 2: Connections to Natural and Cultural Resource Studies in Alaska’s National Parks.

Stromquist, L. 2005.

Mining and Mitigation: The Coal Creek Remediation. Alaska Park Science Journal, Vol. 4, Issue2: The Legacy of ANILCA.

Burghardt, J.E., E.S. Norby, and H.S. Pranger II. 2013.

Interim inventory and assessment of abandoned mineral lands on National Park System lands. Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRTR—2013/659. Fort Col-lins, CO: National Park Service.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 13 Issue 2: Mineral and Energy Development.

Last updated: October 31, 2017