NPS photograph KATM 1469

“BLA—LOOM! Like hell! It is the mountain. The mountain is doing something.” Eyewitness Harry Kaiakokonok, June 6, 1912 (Jessee 1961).

There is a long-standing bond between Katmai’s volcanoes and resident people. In the 10,000 years since the close of the last Ice Age, there have been at least seven explosive eruptions and many minor eruptions in the Katmai volcanic cluster (Fierstein and Hildreth 2001). These events are evident in the archaeological sites throughout the region, where volcanic ash or tephras are layered between prehistoric house floors and camp surfaces. Witnessing the explosion of a mountain in very close proximity was not a novel experience for people living on the Alaska Peninsula, when Novarupta volcano unleashed one of the five largest eruptions in recorded history on June 6, 1912. Although an eruption of this scale had not happened in their lifetime, ancestral knowledge of immeasurable antiquity instructed them through oral tradition:

And then one old man from Katmai…started hollering and telling people about their water...”Put away as much water as you can and store it, reserve it. Wherever ashes come down, there will be no water to drink anywhere...Turn your boats upside down. They will be filled up with ash.” He knows everything, that old fellow (Kaiakhvagnak 1975).

Increasingly severe earthquakes in the days preceding the June 6 eruption led to the complete abandonment of the native villages in the Katmai region (Griggs 1922). Most families were already in Kodiak or Naknek by late May, as men were employed as fishermen and women worked in the canneries during the salmon runs (Davis 1961, Hussey 1971). Remaining residents of Katmai village and the Severnovsk (Savonoski) settlements, fled to Cold Bay (Puale Bay) and to the Bristol Bay coast a few days prior to the main eruption.

Yet this was the time of year to begin to lay away stores of dried fish and meat for the winter, so some families were out on the land hunting and fishing. They experienced the eruption first hand. Two families from Katmai village, a large coastal settlement with a trading post and Russian Orthodox Church, were fishing in Kaflia Bay, a trip of 35 to 40 miles by kayak northeast of Katmai village (Kaiakhvagnak and Kosbruk 1975). Other families from Kaguyak, a village northeast of Kaflia, were also putting up fish in the bay. Five people employed by a commercial fishing interest were stationed in Kaflia Bay at the time. It was from the fish camp at Kaflia, about 32 miles east of Novarupta and in the direct downwind path of the ash fallout, that six-year-old Harry Kaiakokonok witnessed the eruption.

NPS photograph

And then afternoon - sometime in the afternoon - it was just like this, bright sunshine, hot, no wind, that’s when the volcano started. Started snowing like that fine pumice coming down. Make a lot of noise, the size of rice, some of it, some of it smaller, and some of it bigger, and some of it was as big as a kettle or pot. Kaflia Bay started to get white gradually. That water used to be blue, flat calm, no wind; and started to get white, white, white, and pretty soon all white and dark, dark came. Dark didn’t come all of a sudden, it comes gradually. Getting darker and darker and darker and darker, and pretty soon, pitch black. So black even if you put your hand two or three inches from your face outside you can’t see it ‘cause it was so dark...And then the people started to gather up. (Kaiakhvagnak 1975).

Closer to the volcano still were residents of the interior Severnovsk (Savonoski) settlements, among them Petr Kayagvak (American Pete) who was in the process of moving his belongings from Iqkhagmiut, where his wife Pelegia was born, to Old Savonoski when the eruption started.

The Katmai mountain blew up with lots of fire and fire came down trail from Katmai with lots of smoke. We go fast Savonoski. Everybody get bidarka (skin boat). Helluva job. We come Naknek one day, dark, no could see. Hot ash fall. Work like hell (Griggs 1922).

The initial stages of the eruption inspired excitement not fear among the children. They began to run up the hillside near their Kaflia camp, to get a better look at the “smoky mountain,” where they watched vivid lightening, a rare occurrence here, and felt the earth “never stop moving.”

NPS photograph KATM 00236

And we start to run as hard as we can. We don’t run home. We run up the side of high hill. Everybody try to get to top of hill first. All hollering, “Let’s go see the mountain.” One of the childrens was blind. He blind all the time. He can’t see anything. But he running right by me, and he hollering louder than anybody, “Let’s go see the mountain.” Then he fall down, and I help him up and put both his hands on my shoulders...He run behind me, holding onto my shoulders, hollering loud...We get to top of hill and see sky get black all over, way we looking. All full of lightnings. We don’t know what those lightenings are. We don’t see no lightnings before. Then our parents start hollering for us to come to our barabaras, and we run back down the hill, that blind boy still holding onto my back. (Jessee 1961).

The adults rushed to fill available containers with water, and because they had been salting and smoking fish to sell to a trader from Kodiak, as well as drying it for their own use, they were somewhat prepared to gather together and outlast the eruption in their recently built homes. Harry Kaiakokonok’s parents and uncle had built cabins at Kaflia some two years earlier and now spent winters and summers there (Kaiakhvagnak 1975).

This was early twentieth century America, yet for Katmai people life was a blend of strong traditional ways and modern influences. Rifles were owned, purchased with wages or from the sale of pelts, yet the bow and arrow were still used for hunting. Traditional nets and spears were preferred for fishing. Harry remembers hunting porpoise in the bay with his father, Vasilii, who could “make a noise...call them, right up to the side of the kayak.” He would shoot the porpoise with a rifle, then quickly, before it could sink, he speared it with a traditional wooden spear to keep it afloat (Kaiakhvagnak 1975).

The ash darkened the sky for three days. Had it not been for a big whale that drifted ashore providing oil for lamps and torches, there would have been no light for the people at Kaflia, who no doubt wondered whether they might see sunlight again (Kaiakhvagnak 1975). The ash heated the air and it was difficult to breathe.

It get hot in those barabaras. We pull off all our clothes. We soak them in water and put them over our face. Those peoples who have mosses in their barabara pour water over those mosses and put them over their nose and mouth so they can breathe. After a while we open the door and try to see out. All black, everywhere. A little bird fly into barabara. He can’t see where he go. We childrens wash his eyes with water and he stay in barabara with us. (Jessee 1961).

NPS photograph

Eighteen year-old George Kosbruk, who was also at the Kaflia fishing camp, remembered his first glimpse of the post-eruption world. As the ash settled and light returned, people escaped the cramped and dark confines of their shelters:

...light is coming. Oh boy, just like snow. Can’t see nothing. No kind of tree. All white to mountain. No kind of beach. No bluff. Nothing. All white, the big river. Filled up. No running, the water. Just like cement. That time get hard, boy. Lots of animals that time killed. Lots killed – the bear…ducks and everything (Kosbruk and Shangin 1975).

Porpoises, birds and fish were floating on ash and pumice several feet deep, choking the bay. There was no drinking water and little to eat. In that first light, the elders got together and chose nine young men, George Kosbruk among them, to paddle three kayaks across Shelikof Strait to Kodiak for help (Kaiakhvagnak 1975). On Wednesday June 12, the tug Redondo loaned to the Coast Guard by Superintendent Blodgett of the St. Paul Kodiak cannery and under the command of Second Lieutenant W.K. Thompson, anchored in Kaflia Bay at 2:30 in the morning.

Landed and found natives destitute, but apparently in normal health, and very badly frightened. Volcanic ashes had buried village to a depth of three feet on the level, closing all streams and shutting off the local water supply. Salmon were dead in the lake, and as it was apparent that the fish would not return for some time, I gathered all natives, with cooking utensils, bedding, and boats, and placed them on the Redondo. The village was comprised of natives from Cape Douglas to Katmai, seismic disturbances having caused them to abandon their usual camps and seek mutual protection at Kaflia Bay. In addition to the refugees, found five natives employed by salmon fishery located at this point. From all information gathered from the head men, I judged that all natives along the coast had been accounted for, and therefore stood out of Kaflia Bay at 10:30 p.m. …At present there are no natives on the mainland between Cape Douglas and Katmai, the region most affected by the eruption, they having been transported to Afognak by the Redondo. (USRCS 1912).

NPS photograph

One month after the eruption, some of the Katmai refugees, 78 in number, boarded the U.S. Revenue Cutter Manning to return to the Alaska Peninsula and establish a new village (USRCS 1913). Senior Captain W.E. Reynolds, commander of the Bering Sea Fleet Revenue Cutter Service, decided not to resettle the villages on the Katmai coast and to “centralize” the former residents in a new place, at the head of Ivanof Bay (Hussey 1971). The Katmai people were not happy with this selection, citing the rainy weather and concerns about reported winter snow and ice conditions. So, three weeks later a new site was selected that had a beach suitable for landing skin boats, a plentiful supply of driftwood, abundant animal sign, fresh water nearby, and well-drained high ground for homes. Located 200 miles (320 km) southwest of Katmai village and neighboring the former village of Mitrofania, this new settlement was named Perry (now Perryville) after K.W. Perry, Captain of the Manning. Though now far from home, this village was in the familiar shadow of an active volcano, this time it was Mt. Veniaminof, which had last erupted 20 years earlier. Perryville is a successful community of 143 today and remains a seat of Alutiiq culture and language for people of the middle peninsula (Morseth 2004).

According to Pelegia Melgenak (American Pete’s widow), there were two families that lived at Old Savonoski for a year after the eruption before joining others who had resettled on the lower Naknek River at New Savonoski (Davis 1961). She remembered especially how warm the ground and water remained for a year after the eruption; clothes were not needed for warmth, “just like they never have winter.” A new chapel was built in New Savonoski, dedicated to Our Lady of Kazan as was its predecessor in Old Savonoski. New Savonoski has since been abandoned for a nearby village, South Naknek, five miles downriver at the mouth of the Naknek River.

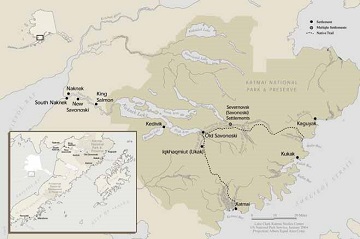

The native villages Katmai, Kaflia, and Kaguyak on the Pacific coast, and the Severnovsk settlements were abandoned during the eruption and were never re-established (Black 1984, Dumond 2010). These villages had been closely knit culturally through language, kinship, shared hunting territories, and trade for untold generations. Recent archeological surveys along the Savonoski River documented a long-standing pattern of periodic village relocation within drainage systems beginning at least 1,700 years ago (Hilton 2002). This is in keeping with ethnohistoric records of changing village locations and names throughout the nineteenth century and until the eruption (Black 1984, Dumond 1988, Davis 1954). Harry Kaiakokonok’s genealogy illustrates the close ties among these villages, with his parents, paternal and maternal grand and great-grandparents born, married and buried variously in Katmai, Kaguyak, Iqkhagmiut (Ukak) and the other Severnovsk settlements (Arndt 2000).

NPS photograph

A network of trails, along waterways and over mountain passes, further articulated the relationships among these villages as well as use of this broad region as a home territory. As a young man, George Kosbruk remembers kayaking routinely from Katmai village, to Kukak and Kaflia Bays, to Kaguyak, from there to Kodiak, or south to the Chignik area (Kosbruk and Shangin 1975). He would also take his single-hole kayak up the Katmai River, over Katmai Pass and down into the Naknek Lake system and Brooks River (Kedivik). From there he could access the Bristol Bay coast. Another important native trail connected the inhabitants of the Severnovsk villages to Pacific coast settlements via the Savonoski and Ninagiak River watersheds.

By some accounts, the eruption did not have a significant impact on vegetation or on large terrestrial and marine mammals outside the immediate scene of the eruption, but seriously affected other subsistence resources such as small land mammals, birds and fish. Few fish were able to spawn in the ash-filled streams, and the recorded salmon catch on Kodiak showed a significant decline between 1915 and 1920. There was a return to normal numbers, and it is estimated that all areas occupied prior to the eruption may have been habitable 10 to 20 years after the eruption (Dumond 1979). By that time, however, President Wilson had signed a proclamation establishing Katmai National Monument on September 24, 1918, inclusive of all the above-mentioned village sites. Annual, month-long bear hunts along the Savonoski by American Pete and other former residents were re-established by this time, and continued at least until 1939 (Hussey 1971). Salmon harvesting within the Naknek Lake system, particularly along Brooks River remained active through the 1960s and is an important interest today. But the likelihood of returning permanently to live was summarized by American Pete in 1918, “Never can go back to Savonoski to live again. Everything ash” (Griggs 1922).

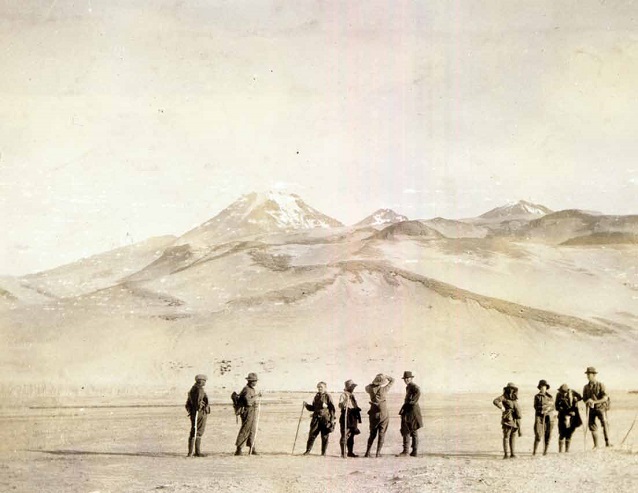

National Geographic Society Katmai expeditions photographs, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage

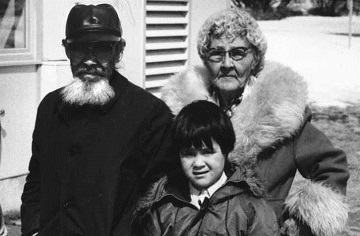

Harry Kaiakokonok became chief of Perryville in 1930 and was a church leader for many years before becoming a priest. His early accounts of the eruption, written down some 30 years after the event, were described as “wonderfully articulate” with Harry “bounding from his chair…..to illustrate salient points with superb histrionics and graphic pantomime” (Jessee 1961). Interviewed by National Park Service ranger Michael Tollefson and archaeologist Harvey Shields another 30 years later, his stories had become more reflective and detailed. The birthplaces, former homes, camp sites and burial places of Harry’s family and kinsmen all lie within the boundaries of what is now Katmai National Park and Preserve. When questioned about the establishment of the park, Harry asked first whether hunting would be allowed there. When told it would not be allowed in the park, he said, “That’s a good way to preserve lots of animals for the future” (Kaiakhvagnak 1975).

Although permanent native villages in Katmai were eliminated by the eruption, strong and enduring ties to their homeland are retained by today’s Katmai descendants. A regrettable consequence of village abandonment was the loss of carved wooden ceremonial masks from Old Savonoski.

NPS photograph

On our trips back to our ancestral homeland near Brooks Camp...in what is now Katmai National Park, as far back as I can remember, our father Trefon Angasan, would look toward Old Savonoski where he was born, roclaiming, “There are masks in the caves.” Anyone within hearing range would smile with contentment that the masks our ancestors carved and used in ceremonies were safely tucked away. In 1993 (we learned) that Harry Featherstone removed the masks in 1921. The news violated our sacred trust. President Wilson had declared the area a National Monument in 1918. How could this happen? (Nielsen 2001).

Harry Featherstone was a trapper who had built a cabin at the head of Naknek Lake. Documents indicate that Featherstone decorated the walls of his cabin with 35 masks that he had removed from an overhang near Old Savonoski (Clemens and Norris 1999). Fortunately, he gave seven of the masks to a Naknek schoolteacher, who in turn placed them in the Alaska Territorial Museum, now the Alaska State Museum in Juneau. The whereabouts of the others is unknown and remains one of the deepest concerns of the Katmai descendants.

NPS photograph

Today Brooks River is the heart of a nationally significant cultural area designated a National Historic Landmark Archaeological District in 1993 (McClenahan 1989). Clustered on former river and lake terraces are dimples in the surface representing over 800 prehistoric house depressions, infilled by post-habitation ash fall and sedimentation. These villages and camps are as old as 4,500 years and as recent as 300 years old; some settlements were as large as Katmai village, Kaguyak and the Savonoski villages in their prime. Archaeological investigations began along Brooks River in 1952 and continue today, with NPS excavations at the “Cut Bank Site”, a 500-year-old village rapidly eroding along the bank of the river below the popular bear-viewing falls. While the unique and fascinating culture history is well-known among archaeologists, few visitors to Brooks Camp are aware of it.

NPS photograph

The great eruption of 1912 deposited over 600 feet of ash in a once verdant, resource-rich valley, effectively sealing its prehistoric record for as many more lifetimes as those already spent there. We know from coastal sites and those scattered throughout the park that this valley had been home to people as early as 8,000 years ago. On a windswept ridge near the outer edge of the Valley of 10,000 Smokes, the tiny, sharp stone blades, called microblades, remaining from a small hunting camp occupied millennia ago, attest to the story buried beneath the ash in the valley.

NPS photograph KATM 03:3:12:24

The flu epidemic of 1918 took a heavy toll among the Katmai people, prompting one historian to predict that “if present population trends continue, the name Savonoski may be kept alive in the future only in literature and as a historic site in Katmai National Monument” (Hussey 1971). To make sure that never happens, The Council of Katmai Descendants formed as a group in 1994, dedicated to the purpose of preserving their members’ cultural heritage primarily through youth education. The group represents the descendants of the Katmai people scattered by the 1912 eruption and who today are represented by over 30 separate geographically-based native organizations.

References

Arndt, K. 2000. Letter to Jeanne Schaaf dated October 17, 2000. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

Black, Lydia T. 1984. Letter Report to J.W. Tanner, Alaska Regional Office, National Park Service. Review of records of the Alaska Russian Church Collection, dated July 31. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

Clemens, J., and F. Norris. 1999. Building in an Ashen Land: Historic Resource Study of Katmai National Park and Preserve. National Park Service, Alaska Support Office. Anchorage, Alaska.

Davis, W.S. 1954. Archaeological Investigations of Inland and Coastal Sites of the Katmai National Monument, Alaska. Report to the National Park Service. Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon, Eugene.

Davis, W.L. 1961. Mount Katmai, Alaska Eruption. Transcript of audio recording of interviews with Novarupta eruption survivors, including Pelegia Melgenak. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

Dumond, D.E. 1979. People and Pumice on the Alaska Peninsula. In Volcanic Activity and Human Ecology, edited by P.D. Sheets and D.K. Grayson, pp. 373-392. Academic Press. New York.

Dumond, D.E. 1988. Final Report to NPS on Field and Library Work Conducted in or related to Katmai National Park and Preserve. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

Dumond, D.E. 2010. Alaska Peninsula Communities Displaced by Volcanism in 1912. Alaska Journal of Anthropology 8(2): 7-16.

Fierstein, J., and W. Hildreth. 2001. Preliminary Volcano-Hazard Assessment for the Katmai Volcanic Cluster, Alaska. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 00-489.

Griggs, R.F. 1922. The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. National Geographic Society. Washington, D.C.

Hilton, M.R. 2002. Results of the 2001 Interior Rivers Survey: Reconnaissance-Level Pedestrian Survey of Alagnak and Savonoski River Corridors, Katmai National Park and Preserve, Alaska. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

Hussey, J.A. 1971. Embattled Katmai; Katmai National Monument Historic Resource Study. National Park Service, San Francisco.

Jessee, T. 1961. Letter from Tom Jessee to Dr. Luther Cressman, June 12, 1961. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

Kaiakhvagnak, Khariton [Hariton] (Harry Kaiakokonok). 1975. Interview with Michael Tollefson, April 29, 1975. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

Kaiakhvagnak, K., and G. Kosbruk. 1975. Interview with Michael Tollefson and Harvey Shields, October 22, 1975. Katmai

archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

Kosbruk, G., and F. Shangin. 1975. Interview with Michael Tollefson and Harvey Shields, October 21, 1975. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

McClenahan, P. 1989. Brooks River Archeological District National Historic Landmark Nomination. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

Morseth, M. 2004. Puyulek Pu’irtuq! The People of the Volcanoes: Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve Ethnographic Overview and Assessment. National Park Service, Anchorage, Alaska.

Nielsen, M.J. 2001. The Missing Masks of Savonoski, Katmai Country, May 11, 2001. Katmai archives in the Alaska Regional Curatorial Center, Anchorage, Alaska.

USRCS (United States Revenue Cutter Service). 1912. Annual Report of the United States Revenue Cutter Service for the Fiscal Year ending June 30, 1912. Washington Government Printing Office.

USRCS (United States Revenue Cutter Service). 1913. Annual Report of the United States Revenue Cutter Service for the Fiscal Year ending June 30, 1913. Washington Government Printing Office.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 11 Issue 1: Volcanoes of Katmai and the Alaska Peninsula.

Last updated: August 17, 2017