Art has entwined nature, culture, and science for centuries. Alaska’s artistic heritage is part of a long and important tradition for understanding, sharing, and preserving parks and related protected areas. Long before the concept of the parks was framed, artists and their art works were already inspiring support for exploration, and sometimes for protection of the special places they knew.

Introduction

Smithsonian American Art Museum. Lent by the U.S. Department of the Interior Museum

Art has entwined nature, culture, and science for centuries. Alaska’s artistic heritage is part of a long and important tradition for understanding, sharing, and preserving parks and related protected areas (i.e., preserves, monuments, and refuges, hereafter referred to as “parks”). Long before the concept of the parks was framed, artists and their art works were already inspiring support for exploration, and sometimes for protection of the special places they knew.

Artists as Interpreters and Advocates for Protected Areas

NOAA

Artists have accompanied explorers on many expeditions, from which they brought back images of grand vistas, strange and beautiful life forms, diverse cultures, unspoiled skies, waters and landscapes, and some of the earliest visual records of places that would later be set aside as parks (Figure 2). Artist George Catlin is credited with having first coined the idea, in 1832, for establishing “a nation’s park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty” (Mackintosh 1999).

When explorers and travelers landed in Alaska, they encountered well-developed indigenous art traditions, which had been refined through thousands of years’ experience with wood, ivory, minerals and other natural materials (Figure 3). Collectors acquired art for patrons and museums, and artists depicted local arts in their own sketches, paintings and photographs (Figure 4). Then as now, art contributed to broader understanding, appreciation, and interest in Native cultures (Figure 6).

By the 1850s, field photography had begun to supplement the traditional place of hand-drawn art for making detailed visual recordings (Balm 2000); however, the advent of photography did not stifle public interest in other art forms. In the latter half of the 19th century, most of the images from expeditions into the American West were black and white photographs, including those by Thomas Moran’s protégé William Henry Jackson. While impressive in their own right, the monochrome photographs did not produce the same impact as a master artist’s colorful paintings, notes Alaskan artist Mark McDermott (personal communication).

By the 1850s, field photography had begun to supple-ment the traditional place of hand-drawn art for making detailed visual recordings (Balm 2000); however, the advent of photography did not stifle public interest in other art forms. In the latter half of the 19th century, most of the images from expeditions into the American West were black and white photographs, including those by Thomas Moran’s protégé William Henry Jackson. While impressive in their own right, the monochrome photo-graphs did not produce the same impact as a master artist’s colorful paintings, notes Alaskan artist Mark

Alaska State Library, P87-0296, Winter & Pond Photograph Collection

John James Audubon (1785-1851), George Catlin (1796-1892), and other naturalist artists had sparked public interest in the American West well before Thomas Moran joined Ferdinand Hayden’s Yellowstone expedition

in 1871. When Hayden reported back to Congress, he proposed setting Yellowstone aside as a public park, and accompanied his argument with images by Moran and Jackson. Moran was hard at work on his monumental painting of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone (Figure1) when the Yellowstone Act was signed into law in 1872 (Macdonald n.d.). The painting that Congress purchased from him captured the public’s attention and firmly established Moran’s reputation as an artist. A year later, Moran joined Major John Wesley Powell’s expedition down the Colorado River, and went on to paint many places that were destined to become national parks.

The artists and illustrators working in America’s west generally relied on patrons, business commissions, and sales for income, unless they had a family fortune. In 1892, Edward Ripley, who headed the Atkinson, Topeka and Santa Fe (AT&SF) railroad, invited Thomas Moran to return to the Grand Canyon to paint at the railroad’s expense. In a stroke of promotional brilliance, Ripley also asked for the reproduction rights to one painting of his choice. The AT&SF distributed thousands of lithographs of Moran’s The Grand Canyon promoting tourism to western destinations that were served by rail. Tourists flocked west, and the railroad provided artists and illustrators with free travel and a market for selling their works (Taggett and Schwartz 1990).

E.W. Merrill, 1929

By the early 1900s, painters were feeling financial pressure from the expanding influence of photography. Some shifted away from representational art, towards other art movements, but photography did not erase the appeal of handmade art. Art’s persistence through the centuries stems from the creative and expressive elements of each artist’s style, their unique ways of interpreting subjects, and sometimes the artist’s ability to frame images not amenable to photographic techniques, such as historic and prehistoric reconstructions (Figure 5).

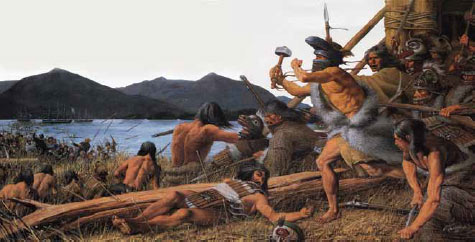

Most of Alaska’s national parks, refuges, and wilder-ness areas (and most of America’s) owe their existence, in part, to the accomplishments and support of artists and photographers. Sitka National Monument was established in 1910, with the dual purposes of commemorating an important Tlingit-Russian battle site and preserving and displaying a collection of historic totemic art. The totem poles were originally acquired throughout southeastern Alaska by Territorial Governor John G. Brady for display at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase and 1905 Lewis and Clark Expositions (Patrick 2002). They remain a centerpiece of the park visitor’s experience today.

Western landscape and wildlife painter Belmore Browne joined Andrew Jackson Stone’s mammal collecting expeditions for the American Museum of Natural History in 1902 and 1903. Browne was an accomplished outdoorsman and explorer, who also participated in three pioneering attempts to scale Mt. McKinley between 1906 and 1912. He produced the first known painting of North America’s tallest mountain in 1907 (Woodward 1994). Browne joined naturalist Charles Sheldon in lobbying Congress successfully for establishment of Mount McKinley National Monument in 1917 (now part of Denali National Park and Preserve).

Figure 5. The artwork depicts the 1804 resistance to Rus-sian occupation by warriors of the Tlingit Kiks.ádi clan. War Chief K’alyaan (Katlian), wearing a carved Raven mask and armed with a blacksmith’s hammer, leads the Tlingit charge from their fortified palisade Shis’kí Noow.

UA903-9. UA Museum of the North

Fig 6. The dancer in movement interprets “Something Lies over in that Place”.

Smithsonian Archives, Record Unit 7243, box 1, folder 8, image #SIA2011-2259

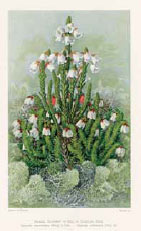

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of the photographs, etchings, and paintings of Alaska’s southern coasts produced by the Harriman Alaska Expedition of 1899 (Burroughs et al. 1901). Louis Agas-siz Fuertes’ bird illustrations, R. Swain Gifford’s and Frederick Dellenbaugh’s landscapes (Figure 7), Frederick A. Walpole’s botanical illustrations (Figure 8), Charles R. Knight’s mammals, and C. Hart Merriam’s and Edward S. Curtis’ photographs were more than just documentary recordings. They captured the essence of lands, waters, and peoples still largely unknown to the rest of the world, and interpreted them through the focused eyes of artists. The Harriman Expedition illustrations also provided the visual baseline for assessing change, when their route was retraced by a team of scientists, artists, and writers 100 years later. Alaskan artist, historian, and professor emeritus Kesler Woodward (Figure 9) served as artist-in-residence for the Harriman Expedition Retraced.

Smithsonian Archives, Record Unit 7243, box 1, folder 28 image #SIA2011-2260

A. Walpole’s botanical illustrations (Figure 8), Charles R. Knight’s mammals, and C. Hart Merriam’s and Edward S. Curtis’ photographs were more than just documentary recordings. They captured the essence of lands, waters, and peoples still largely unknown to the rest of the world, and interpreted them through the focused eyes of artists. The Harriman Expedition illustrations also provided the visual baseline for assessing change, when their route was retraced by a team of scientists, artists, and writers 100 years later. Alaskan artist, historian, and professor emeritus Kesler Woodward (Figure 9) served as artist-in-residence for the Harriman Expedition Retraced.

In 1912, when Novarupta volcano erupted vio-lently on the Alaska Peninsula (Figure 10), the National Geographic Society (NGS) sponsored five years of research by Robert F. Griggs and associates. Their work resulted in a series of stunning documentary photographs, magazine articles and a monograph (Griggs 1922). Griggs and the NGS used the products of their work to lobby Congress successfully for National Park Service protection, which occurred in 1918.

Photograph taken by M. Honneg, 1913.

About the same time, artist, illustrator and author Rockwell Kent found inspiration in isolated coastal Alaska. Critics praised his illustrated book, which described the year he spent with his young son in Alaska’s Resurrection Bay (Kent 1920). Kent’s art and writing influenced the way people would view Alaska, their concept of wilderness and the area that would become Kenai Fjords National Park in 1980

(Doug Capra, personal communication). Kent went on to become one of the best recognized American artists of the 20th century (Cook and Norris 1998).

By the late 1920s, the commercial markets were in decline for artists. Magazines had shifted to photographs, and many artists and illustrators found it difficult to earn a living (Taggett and Schwartz 1990). When the national economy collapsed during the Great Depression, they could no longer look to their patrons for support, and thousands of artists joined the ranks of the unemployed across the country.

National Park Service Collection, Sitka National Historical Park

Four of President Roosevelt’s Depression-era New Deal projects were designed to put artists back to work, use their talents to revive the dispirited American populace, and to decorate federal buildings. The Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts established a precedent for today’s popular “one-percent for the arts” programs, by allocating 1% of new construction costs to fine art (Raynor 1997).

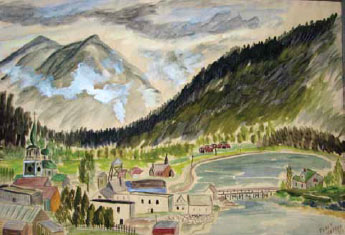

Similarly, the Works Progress Administra-tion (WPA) used a 1% formula to support the Federal Art Project (FAP), which employed artists, including the 12 artists of the 1937 Alaska Art Project. Collectively, the New Deal artists created hundreds-of-thousands of paintings, murals, sculptures and limited edition prints between 1933 and 1943 (Figure 11). These artists were federal employees, or sometimes contractors, so their art became public property.

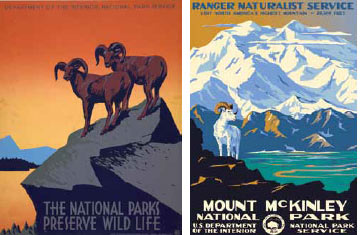

FAP artworks were initially offered to any city, state, or federally-supported institution, but when funding for the FAP ended in 1943, the remaining artworks were simply sold by the pound as scrap canvas (Morse 1960). Although WPA workshops produced more than two million posters from 35,000 hand-drawn, woodcut, lithograph and serigraph designs, only about 2,000 original WPA posters are

still known to exist (Library of Congress, Posters for the People).

The posters in the National Parks series were nearly lost, but today they continue to inspire popular contemporary works of art (Ranger Doug) (Figure 12).

Left: Library of Congress (left), Right: © Doug Leen

Brothers Adolf and Olaus Murie were accomplished wildlife biologists, authors, wildlife artists, illustrators, and resource protection advocates (Figure 13). The Muries’ classic ecological studies changed the way predator and prey populations were managed by federal agencies. While serving as president of the Wilderness Society, Olaus led the successful campaign to protect what would later become the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. After his death in 1963, Olaus Murie’s wife, Margaret, successfully pursued protection for more than 100 million acres of Alaska with passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act in 1980 (ANILCA).

America’s conservation movement also owes much to art photographers like Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter. Adams’ striking monochrome images of the American West have epitomized places like Yosemite and Denali since the 1930s, and they piqued public interest in seeing these places firsthand. Porter’s influential second book The Place No One Knew, Glen Canyon on the Colorado (1963) was part of the Sierra Club’s campaign to prevent flooding of Glen Canyon by the dam of the same name. Although the dam was completed and Glen Canyon submerged under the rising waters of Lake Powell, their campaign focused attention on other proposed reclamation projects and helped to ensure passage of the Wilderness Act, which had previously been stalled in Congress (Getty Center 2006).

What Makes Art Influential?

Image courtesy of the Murie Center Archives

Artists have played major roles in the protection of most of the park lands, refuges and wilderness areas in Alaska, and by sheer size of area, for most of America…but what is it about art that makes it influential?

Art is personal and individual. People are inspired by art that reflects their ideals, dreams, and aspirations. Art that stirs strong emotions can also shift thinking and spur people to take actions. Park superintendent Paul Anderson recalls that people in the eastern U.S. who supported the creation of parks in the western U.S. had never visited those places. They saw these parks, however, through the eyes of others, such as Thomas Moran, Albert Bierstadt and John Muir, and were moved to take action (personal communication).

Art does not need to be realistic, or even serious, to be influential. How many people can trace their own interest in nature and science back to the illustrations in a beloved children’s book (Figure 14), the cover of an adventure story, or even a memorable series of comic strips? Art helps people to connect to a place, and provides another way to relate new experiences to ones from before (Mark McDermott, personal communication). Recognition and originality are equally important for art to make an impact. People need to relate to the art, but to capture their attention an artist needs to portray things in ways that were not already familiar to the viewer (Kesler Woodward, personal communication).

Art transforms people into active observers and provides a starting point for empathy with the subject, as people learn to see the world through the eyes of an artist (Maria Coryell-Martin, personal communication). When the artist is able to capture the power and the emotional impact of what they are seeing, their art will “strike a chord” with others (Kurt Jacobson, personal communication).

C.J. Rea

Images are more influential and sometimes more subtle than words, explains Kesler Woodward. Propaganda and advertising work so well because their images feed directly into our human consciousness, bypassing the cognitive filtering that occurs when we read or hear words. Woodward mentions the paintings of Sydney Laurence (1865-1940) as examples of how artistic perspectives can affect audience impressions for years to come. Laurence was Alaska’s best recognized landscape artist, and he produced iconic works of monumental proportions, where people seemed small and insignificant in comparison to the grand landscape. Laurence’s vision has become so ingrained in the culture of Alaska and the American West, suggests Woodward, that it can still lull us into imagining that any human impacts would also be insignificant on so massive a landscape (Figure 15).

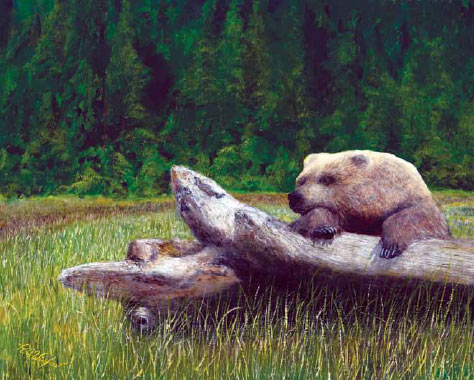

Alaska Airlines Foundation, on loan to the Anchorage Museum

Controversy can also bring art to the public consciousness, notes Alaska artist David Mollett (personal communication), referring to proposed drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). Mollett led many artists on trips into ANWR between 1988 and 2000, and saw the effect the landscape had on the artists, and the effect their art had on others (Figure 16). Photog-rapher Subhankar Banerjee, also travelled extensively through the refuge. Banerjee’s pictures (2003) were thrust into the limelight when they were shown during a contentious Senate debate over drilling, and again when his photo exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution was moved to the building’s basement. His new exhibit space may have been less conspicuous, but controversy over the presumed political interference propelled Banerjee’s pictures into the limelight and his career into the gallery, museum and lecture circuit for years.

Park and Expeditionary Art Programs Today

www.arcticrefugeart.org/mollett.html

Parks preserve natural and cultural heritage and contain some of the world’s most spectacular viewscapes. It is only natural that these lands and waters attracted artists long before they became parks. Artists have contributed greatly to conservation of these areas, and their artwork is now a crucial component of our heritage.

The breadth of styles, media, and materials that are available to artists has never been wider than today. Artists benefit from a broad popular market and a variety of pro-grams that lend support to the arts, including programs focused specifically on parks, nature, culture and science.

Park-Focused Art in Schools and Communities

www.kurtjacobson.com

Park educator C.J. Rea has seen art work magic with youth and adults (personal communication). For several years, Rea has worked with Seward artists to bring art into every K-12 classroom in the community. For elementary and middle school students, the park-themed classes may be their first experience with art instruction, and for high school students, working with volunteer artists can help them to gain confidence, inspiration, and encouragement to experiment with new media and new approaches. Kenai Fjords National Park also sponsors a community Art for Parks show, where the students are encouraged to show their artwork.

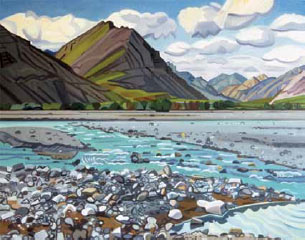

Community-based art programs help forge connec-tions between residents, organizations, trails and land-scapes (Bianchi and Tracy 2008). Kurt Jacobson (Figure 17) sees art competitions and art events in parks as wonderful ways to encourage adults and youths to get outdoors and engage with their parks (personal communication). Jacobson is working with the Alaska State Parks, other plein air painters, and visual and performing artists to create a continuing series of artistic performances, demonstra-tions, and community events at parks across the state.

Park-Focused Art Competitions

www.markmcdermottart.com

The public sometimes attributes art to natural talent, but artists say it is more a product of passion refined by continuous practice (Maria Coryell-Martin, personal communication). Success as an artist takes

“miles of experience behind a brush”, perseverance, and sometimes a thick skin for receiving critical review (Kurt Jacobson, personal communication). The artist’s work also needs to be seen by others, preferably those who can make a difference. Juried competitions can be great ways for early- to mid-career artists to have their work seen by broader audiences and for parks to publicize themselves (Kesler Woodward, personal communication).

For more than two decades, starting in 1986, the Arts for the Parks program provided nationwide exposure for park-focused art and artists (Wolf 2000, Art for the Parks 2008). The tradition of a nationwide competition and travelling art show about the national parks has since been picked up by Paint the Parks (Paint America 2011).

Kerri Bellisario is working with the NPS to organize new juried exhibitions reflecting on the art, artists, and impact of national park artist in residence programs across the country. Park-focused artists welcome the opportunities provided by such competitions, says Mark McDermott (Figure 19), who reflects that the shows provide good exposure, both for the artist and for the featured parks.

Shows closer to home are also important to artists, to receive feedback from peers and exposure to local audiences. Since 2006, the Alaska Artist’s Guild has sponsored the annual Art for Alaska’s Parks competition to celebrate Alaska’s beauty and showcase representational art inspired by Alaska’s public lands.

Park Artists in Residence

www.expeditionaryart.com

The NPS has a long tradition of welcoming artists. The NPS invited artists to help celebrate America’s bicentennial through its Artists-in-Parks (AIP) program, and in 1984 the NPS established an Artist-in-Residence (AIR) program to perpetuate and expand on the tradition of artists working in parks (NPS 2010). Most artists working in and around parks come as visitors, at their own expense, and on their own time. Superintendent Anderson sees artist in residence programs as another way to help people to make personal connections to the parks, in creating new works of art and experiencing art created by others (personal communication).

At least 10% of the national parks have established competitive programs to further encourage artists, performers and writers by offering amenities ranging from a place to stay (more common), to studio space, a modest expense stipend, or transportation assistance (all less common) (NPS 2009).

Many public lands also offer other types of volunteer opportunities, such as campground hosts and tour guides that can provide artists with access to remarkable places and allow spare time for art and other self-directed activities. A few parks also provide paid opportunities for artists to create and interpret art in a public venue.

The artists selected for a formal residency gain direct and sustained access to park resources, in exchange for which they may be asked to donate an inspired work of art, provide public demonstrations, or both (Kesler Woodward, personal communication). Many artists compete for opportunities to work in an inspirational park setting, gain exposure from park publicity and recognition, and even stay in historic lodgings.

As more artists discover the opportunities in parks, and as more parks begin to utilize online application systems (AKGEO 2011), the competition for relatively few residencies increases (Kesler Woodward, personal communication).

Artists on Scientific and Exploratory Expeditions

The National Science Foundation (NSF) has long recognized the contributions that artists can make to public understanding, and after more than 50 years, the NSF continues to provide in-kind support for artists and writers to work in Antarctica (Office of Polar Programs 2011). The NSF was deeply involved in International Polar Year (IPY), which raised global consciousness of the Arctic and Antarctic, as did it its forerunner 50 years earlier, the International Geophysical Year. From 2007 to 2009, the IPY organized hundreds of individual science projects, some of which incorporated artistic components, into a coordinated international program.

Maria Coryell-Martin has worked as an artist in both the Arctic and Antarctic, developing contacts for fieldwork as an expeditionary artist through networking with polar scientists and managers (Figure 20). Coryell-Martin’s cold climate experience has enabled her to see that wildlife must be highly specialized to survive in harsh polar and glaciated environments, and to understand how that same specialization makes them highly vulnerable to envi-ronmental change.

On returning home, Coryell-Martin uses art and education to tell stories and raise public awareness of the world’s cold regions. Polar Science Weekend events in her hometown of Seattle, Washington, provide Coryell-Martin with venues for connecting with thousands of people of all ages (personal communication).

Encouraging Artists to Contribute to Parks: “America’s Greatest Idea”

Attracting artists to parks

Artists clearly have a role in parks today, and parks have a long history of welcoming artists and publicizing art, but is this enough? Artists understand that most parks were not created to celebrate the arts, and few artists would expect parks to cater to their needs.

At the same time, many more would welcome opportunities to share their creative visions with others. Park managers have not always understood or fully appreciated the power and influence that artists can have with the public, how to attract or how to work with artists, or what to do with contributed art. An artist interested in a well-known park like Denali or Rocky Mountain will find a wealth of information on the internet, but that’s not true for every park. Application processes for artist residency programs vary considerably, and sometimes the application can appear as complicated as an application for employment.

Artists interested in working in more than one park may need to learn and use new computer programs, reformat the images in their portfolios to different specifications for different applications, provide letters of reference, and develop a suite of specific information products for each park.

Park access and facility use

What parks can do best for artists is to provide a place for inspiration. For artists coming from outside the local commuting area, providing a place to stay and work, and perhaps helping with travel expenses can be an attraction. Artists looking to show the park from fresh points of view can also benefit greatly from logistical support, especially in remote wilderness parks. This can be accomplished by pairing one or more artists with staff members already planning field work, and sometimes by organizing trips for several artists at the same time.

For example, the Grand Canyon Trust and Forbes magazine hosted a select group of 15 artists on a 1999 trip down the Colorado River, to raise environmental awareness about the park. Two years later, they held exhibitions for the art in major US cities, published a book, and used the proceeds from sales of donated art for conservation purposes.

Exposure and publicity

Most artists have at least a hint of extroversion…they want their work to be seen by others, and they want it seen in a quality venue. Well organized park-focused shows, designed and publicized with the help of experienced artists and galleries, can be a great boon for artists and parks alike, as can press releases and interviews of the artists.

The rights and responsibilities of owning original art

Providing a piece of art for a prestigious permanent collection can be an honor for any artist. The collections of national and state agencies and museums are no exception. Peer-reviewed (juried and judged) competi-tions have been used for more than a century to identify and select art for shows and permanent collections.

Artists are more likely to donate their best works when they are confident that the work will be well cared for into the future, or that they will receive a fair share of the proceeds if their work is sold. It is important for artists to be informed in advance, and invited to help set a fair price, if a park contemplates selling donated artwork to support the program or manage collection size.

While it is appropriate for a park to ask sponsored artists to provide images for interpretation, education, scholarship, reporting and promotion, the artist’s interest in working in a park should not impair their ability to reproduce, sell and license their work to others.

Conclusions

Bob Winfree

People experience wild and historic places in different ways. Many people who care deeply about wildlife, cul-ture, science and history may never visit Alaska’s remote parks in person.

Art can provide people with a rich park experience wherever they may be, without which many might never appreciate the diversity of special places that are preserved as parks. Art helps people to appreciate our heritage and to understand that such places must still be protected for our children and grandchildren to experience. The historic images captured by landscape, wildlife, portrait and scientific artists and photographers continue to be enjoyed by enthusiasts of art, history and parks today.

While the legacy of earlier generations of artists remains strong, art is not static, and it is not limited to what our eyes can experience. As new media are developed, artists will continue to expand in new directions and stimulate more of our sensibilities. Today, several federal, state and nongovernmental organizations continue to encourage artists to work in parks, sometimes providing venues for exhibiting and interpreting their art, benefiting artists, parks, and the public in the process (Figure 21).

Partnerships with and among artists working in parks provide rich opportunities for people to experience and learn about parks today, and expand the heritage for future generations to share.

Acknowledgements

Most of the artwork that illustrates this article is copyrighted, and is used with the permission of the artist or their institution. The author wants to express thanks to the many people who provided information and images for the article including (in alphabetical order): Ellen Alers, Paul Anderson, Kerrie Bellisario, Doug Capra, Maria Coryell-Martin, Kirk Dietz, Louis S. and Francine Glanzman, Mareca Guthrie, Carol Harding, Kurt Jacobson, Sandra M. Johnston, Doug Leen, Maria Lin, Brian Maebius, Mark McDermott, David Mollett, Wade Myers, C.J. and Ba Rea, Richard Sorensen, Stephanie Stephens, Bryan Taylor, Sue Thorsen, and Kesler Woodward.

Part of a series of articles titled Alaska Park Science - Volume 10 Issue 2: Connections to Natural and Cultural Resource Studies in Alaska’s National Parks.

Last updated: October 26, 2021