Article

Worthington Farm (Clifton) Cultural Landscape

NPS

Introduction

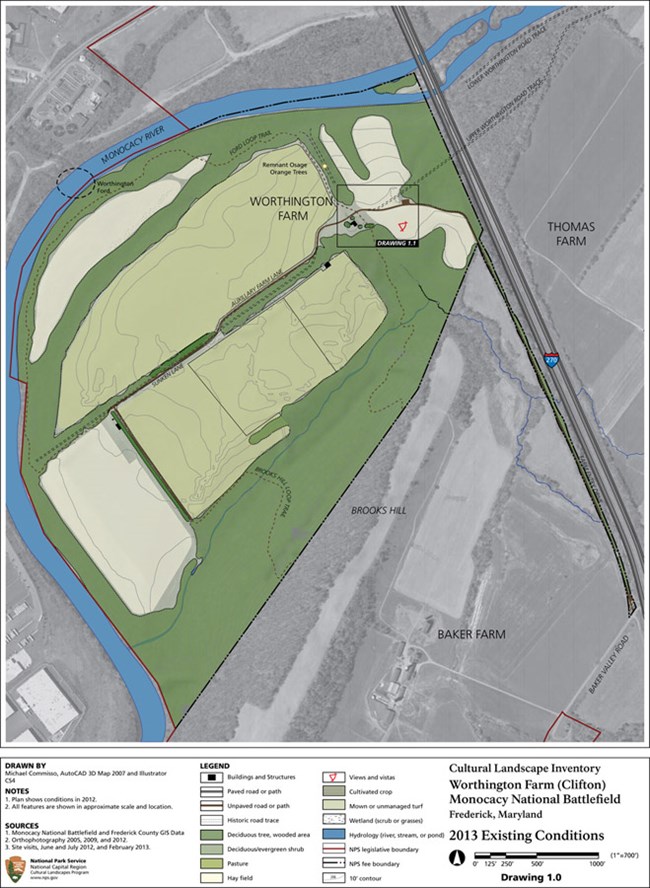

Located about three miles south of Frederick, Maryland on the south side of the Monocacy River, Worthington Farm is a patchwork of rolling fields and forest that represents the broad patterns in the agricultural landscape that were present at the time of the Civil War Battle of Monocacy (July 9, 1864).The Worthington Farm cultural landscape, a component of the Monocacy National Battlefield, is significant in areas of military history, social development, industrial and agricultural history, and architecture. Its period of historic significance begins in 1724, the date of initial patenting and settlement of the land encompassing the property, and extends through the Civil War-era events to the Battle of Monocacy in 1864.

Although Worthington Farm, also known as “Clifton,” has lost some of the features that existed during the Civil War, the landscape retains its historic rural agricultural character in the surviving circulation systems, field and forest patterns, and the main house.

Landscape History & Use

Agriculture on the Monocacy River

Prior to European settlement, Native Americans lived in this area along the Monocacy River. Monocacy National Battlefield contains eleven known prehistoric sites dating from the early Archaic to the late Woodland periods. By the 1700s, speculators and colonial settlers were giving new definition to the landscape through mapping, patenting tracts, and clearing areas for cultivation. Most of the land that now comprises the Worthington Farm was a portion of a 1400-acre land grant called “Wett Work.”

These tracts were generally tied to the intersection and crossroads marking the passage of the Georgetown Pike over the Monocacy River and the Monocacy Junction of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Over time, parcels of property were added, resurveyed, sold, and combined, leading to the 1852 formation of the Clifton property by wealthy agriculturalist Griffin Taylor. Taylor constructed the two-story brick farmhouse on the property between 1851 and 1852.

NPS

NPS / Monocacy National Battlefield Archives

Census figures and studies suggest that the number of enslaved people in Frederick County was low relative to the rest of the state. Additionally, some members of Black families were freed while their family members were still enslaved in the area. In 1840, 17 enslaved people lived and worked on Clifton when it was owned by Griffin Taylor. Ten years later, the number of enslaved people had dropped significantly among all landowners in the Monocacy area.1 Two small one-and-a-half story buildings were located near the south end of the main house. These buildings likely housed the remaining enslaved people owned by Worthington.

NPS

The Farm Becomes a Battlefield

While this transportation corridor contributed to the development of the area, it also became a target for Union and Confederate armies throughout the Civil War because it facilitated movement of troops and supplies. Military activities continued in the Monocacy Junction area throughout the Civil War. At the height of summer in 1864, Confederate General Jubal Early’s forces arrived in Maryland after forcing General David Hunter to retreat from his defensive position at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, thus leaving open the route to Washington, D.C. Early’s forces converged on the Union position that had been established at the Monocacy Junction.

NPS / Monocacy National Battlefield Archives

On July 9, Confederate troops, under the command of General John McCausland, forded the Monocacy River at the Arcadia ford (Worthington/McKinney ford), just downstream from the covered bridge over the Georgetown Pike and on the north edge of the present-day landscape boundary. Once over the river, their march uphill was obstructed by fences and fields full of recently harvested stacks of grain. Union soldiers also lay waiting in their path, relatively well protected by the fence line that ran along the boundary between the Worthington and Thomas farms. The combatants roiled the fields on either side of this line, moving back and forth between the main house at Worthington and the Thomas house in their effort to seize control of the Georgetown Turnpike.

Although considered a Union loss, the Battle of Monocacy proved a valuable defensive effort. Heavy Confederate casualties, a 24-hour delay in the march to Washington, and exhaustion of Southern troops prevented General Early from advancing on the capital city.

Meanwhile, the Worthington family, residing in the house at the time, hid in the basement as the conflict engulfed their home and fields. The house and property were severely damaged during the fighting. Fallen soldiers from both sides were temporarily buried on the property, and the Worthington House was used as a field hospital.

NPS

The Post War Landscape and Preservation Efforts

In 1928, the Monocacy Battlefield Memorial Association - which included Glenn Worthington, who was six at the time of the battle - lobbied Congress for legislation to make the battlefield a national park. In 1934, Congress authorized the creation of Monocacy National Military Park (renamed Monocacy National Battlefield in 1976). In 1953, the Worthington family sold their farm to Jenkins Brother, Inc., a corporate farming operation. The laborers who worked for the company, mostly migrant farm workers, lived in the Worthington House during the months they cultivated the surrounding crops.The house fell into disrepair, the outbuildings were abandoned and allowed to deteriorate, and the band of trees along the field lines and river expanded. Additional woody growth filled in the rectangular-shaped area that formerly contained a garden and orchard located just south of the house. The addition of an interstate in the 1950s, separating Worthington Farm from the adjacent Thomas Farm, also impacted the character of the property.

When the Worthington Farm property was purchased by the National Park Service in 1982, the NPS stabilized the main house and cleared the area around the house of trees. Aside from the area affected by the interstate and the area immediately surrounding the house, the farm’s historic field patterns and spatial relationships remained largely intact.

NPS

Landscape Description

The northern and western boundaries of the Worthington Farm cultural landscape are formed by a curve in the Monocacy River, and the crest of Brooks Hill marks the eastern boundary. The Worthington House is the only remaining building on the 280-acre property that dates to the time of the Battle of Monocacy. The Worthington Farm main house, dating from the early 1850s, is enhanced by fine interior painted decoration that is attributed to Constantine Brumidi, renowned as the creator of the U.S. Capital frescoes. In the 1700s, a number of river crossings were established at low places on the banks of the Monocacy River. Road traces that may be related to these fords are still evident.

Fencing on the Worthington property delineated areas around the clusters of structures at the center of the farm and along certain fields. These included post-and six-rail, picket, and paling fences, as well as living fences and hedgerows, as indicated by the mature Osage orange trees that line a road trace and delineate the rectangular area that contained the kitchen garden.

A pair of White Oaks (Quercus alba) are located on the south side of a historic fence line at the northwest base of Brooks Hill. They stand on either side of what was presumably a path that once led to a small, two-room dwelling house, of which only the stone foundation remains. Given their placement, the trees may have been intentionally planted in the 1800s and may be associated with the history of Worthington Farm's African American community.

The character and features of the Worthington Farm cultural landscape continue to provide an opportunity for visitors to interpret this site’s role in the park’s titular Civil War battle and its aftermath, as well as the agricultural history of this part of the Monocacy River.

Notes

1. Paula Stoner Reed, Monocacy National Battlefield: Cultural Resources Study (Hagerstown: National Park Service, 1999), 28.

Quick Facts

- Cultural Landscape Type: Vernacular

- National Register Level of Significance: National

- National Register Significance Criteria: A, C

- Period of Significance: 1724 - 1864

Landscape Links

- Cultural Landscape Inventory park report: Worthington Farm (Clifton)

- Thomas and Worthington Farms Cultural Landscape Report

- Monocacy National Battlefield Cultural Resources Study

- National Register of Historic Places: Monocacy National Battlefield

- Library of Congress: HALS Documentation

- More about NPS Cultural Landscapes

Last updated: November 6, 2024