Last updated: January 16, 2025

Article

"A Home Away from Home": The Women's Service Club of Boston

National Committee on Household Employment Records, National Archives for Black Women’s History of Mary McLeod Bethune Council House, NHS.

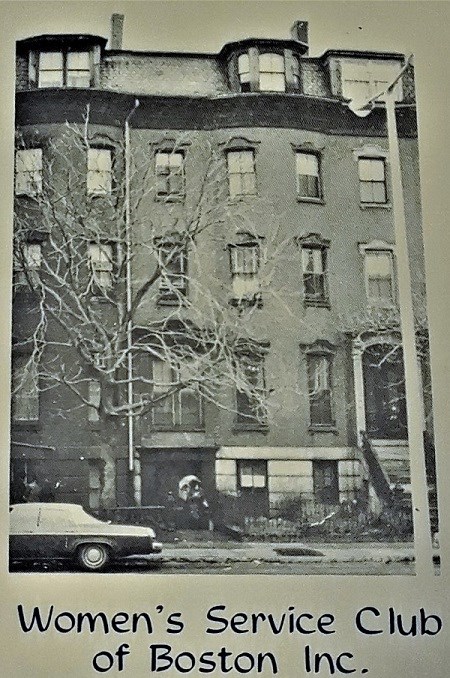

Located along a busy thoroughfare at 464 Massachusetts Avenue in Boston’s South End neighborhood stands a five-story brownstone, one among scores that dot the city’s landscape. What appears as an ordinary building has long operated as a space of empowerment. "464," as locals admiringly called it, is the headquarters of the Women's Service Club of Boston, a volunteer social organization.

Generations of Black women have piloted the Club's efforts over the past century to serve Bostonians of varied backgrounds, including soldiers and students, migrants and mothers. Dedicated to cooperation and community welfare, members' advocacy bridged divisions of race and class and challenged systemic inequality. The Women's Service Club represents the enduring power of Black women’s activism in Boston from earlier eras to the present day.

The Founding of the Club

The Women's Service Club materialized in a period defined by hardening race relations. Boston, otherwise acclaimed as "Freedom's Birthplace" and the "Athens of America," functioned as a hub of abolitionist activity leading up to the Civil War. As the twentieth century unfolded, however, the city's Black residents faced segregation in education and housing. Racism confined the majority of Boston's Black population to menial employment. Many worked as unskilled laborers, porters, laundresses, and domestic workers. Limited access to community recreational opportunities and a desire for their own space compelled Black women to form their own associations.[1]

Participation in patriotic clubs provided an avenue for Black women to socialize and serve their communities in the early twentieth century.[2] In this spirit, local activist Mary Evans Wilson organized a knitting group in 1917 to support soldiers of color fighting in World War I. Hundreds of women joined the group, donating their talents to produce scarves and gloves for Black servicemen.[3] Wilson had, by this time, established her reputation as an advocate for the marginalized.

Born in Oberlin, Ohio in 1866, Mary Evans grew up in a family of anti-slavery activists. She later wrote for The Woman’s Era, an organ of the "Woman's Era Club" founded by Black suffragist Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin in 1893. Following Mary's marriage to civil rights attorney Butler Wilson in 1894, the couple resided in Boston where they raised six children and immersed themselves in protesting racial discrimination, segregation, and lynching. Mrs. Wilson's talents as an organizer surfaced in her recruitment of thousands of members to the Boston chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People during the 1910s while her husband served as its president. The knitting club that Mrs. Wilson used to attract NAACP participants officially incorporated in 1919 as the Women's Service Club of Boston. Buoyed by altruism and middle-class impulses, the Club aspired to promote education and women's involvement in government, as well as philanthropy and community welfare more generally.[4]

Supporting the Community

Humanitarianism guided the activity of the Women's Service Club's over the next half century. The building the Club purchased along Massachusetts Avenue operated as part-meeting space and part-settlement house. "A Home Away from Home," as clients described it, "464" offered affordable shelter to female workers, migrants, and college students barred from on-campus housing due to racist policies.[5] In addition to meeting ordinary people’s basic needs with donations of food, clothing, gas, and medicine, the Women's Service Club delivered academic and vocational instruction as well as job placement. Their services helped women, men, and children alike; one initiative even dispatched clothing and other donations to impoverished residents in the state of Mississippi.

During both World War II and the Korean War, the Club resumed its activities for Black soldiers and their families and also made "464" available to members of the Women's Army Corps, a female military sub-unit, as a lounge for respite.[6] Social affairs such as formal tea parties and annual musical shows celebrated Black heritage and raised money for underprivileged youth to attend summer camp.[7] The Club's activities provided vital humanitarian contributions in an urban center suffering from industrial decline and mounting racial prejudice.[8]

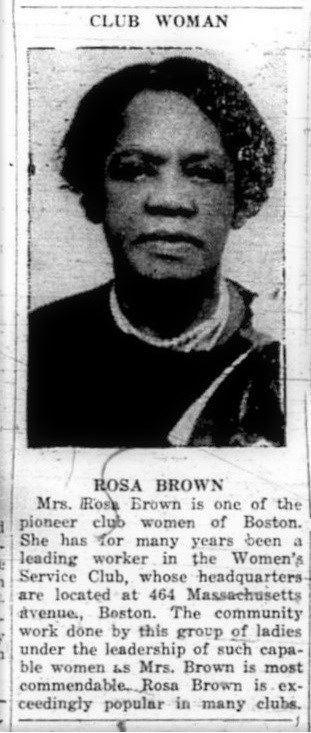

The Chronicle, July 26, 1939

Women such as Rosa Brown sustained the Club's efforts through their devotion to the common good. Born during the Civil War in Richmond, Virginia, Brown migrated to Boston in her youth and spent her adult life raising funds for charity and assisting fellow newcomers to the city. Brown took up social justice causes as well, championing women’s suffrage and challenging the second-class citizenship of Black residents through her membership in organizations such as the Boston NAACP and William Monroe Trotter's National Equal Rights League. Described by one journalist as "the greatest organizer whom the Great Boston Negro community ever knew…," Brown co-founded the Women's Service Club with Mrs. Wilson and served for years as a "House Mother" and Club leader.

Upon her death in 1954, observers likened Mrs. Brown to luminaries such as Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth and celebrated Brown's selflessness, vision, and ability to unite people together. Notably, Brown attracted others to public service and protest, including her daughter-in-law Melnea Cass.[9]

Melnea Cass and Advocacy Efforts

Melnea Cass' early life experiences familiarized her with the hardships of the people she later served as a leader of the Women's Service Club. Born in Richmond, Virginia in 1896, Cass migrated during her childhood to Boston with her family to escape Jim Crow constraints. She soon learned the broader scope of racism upon experiencing Boston employers' discrimination against Black workers.

With limited options as an adult, Cass supported herself and her family by laboring as a domestic worker. She connected her narrow employment prospects to prejudice. Similar to her mother-in-law Rosa Brown, Cass participated in a multitude of organizations from the 1920s through the 1970s and lived by the maxim, "If we cannot do great things, we can do small things in a great way." Her public challenges to employment and housing discrimination as well as school segregation in Boston fortified Cass' reputation as a civil rights leader.[10] Cass sparked the Women's Service Club's most renowned period of activity during her tenure as president from 1962 until 1978.

The Club's advocacy during this period aided thousands of people and helped domestic workers carve out a unique space in an unfamiliar city. Women of color from the South and Caribbean islands regularly filled local positions in household employment. They often fell victim to abuse because Massachusetts excluded domestic workers from formal safeguards such as a minimum wage and maximum hour cap.

As former migrants and domestic employees, Cass and a team of still largely unrecognized Black women developed federally-funded programs in collaboration with the National Committee on Household Employment and Action for Boston Community Development, the city's anti-poverty agency. For over two decades, their initiatives supported household workers of varied ethnic and racial backgrounds with social services, professional training, and legal education.[11] At times, workers rebuffed Club leaders' attempts to manage them. Such guidance, however, originated from genuine concern, and migrant workers such as Louise Kerr found a sense of belonging at "464." As Kerr put it:

the Women's Service Club…was called, "A home away from home." It was a place to go when you didn’t know where [else] to go. This was like a means to an end to get away from that cleaning and dealing with that and just come here and just relax and be with your own people and forget about that for a little while.[12]

Boston's household employees and the Women's Service Club together formed a critical facet of the Civil Rights and Women’s Liberation movements. Though other figures and organizations are better known, these groups' campaign to expand domestic workers' labor rights paralleled broader endeavors to eliminate the second-class citizenship of females and Black individuals. Over several years, they developed legislative proposals that attracted interracial, cross-class, and bipartisan support.

Victory prevailed in 1970 with Massachusetts' passage of the nation's broadest legal protections for household employees since the Great Depression; the Commonwealth now guaranteed domestic workers minimum wage, overtime pay, maximum hour limits, and collective bargaining rights.[13] Melnea Cass later underscored the legislation's meaning for Black women workers, affirming that, "So many black women had done domestic work, and they hadn't been able to be recognized with dignity, and we brought that about."[14] Their pioneering vision became a celebrated national model for contemporary activists and still inspires domestic workers and their allies today.[15]

The Women’s Service Club of Boston, Inc.

Continued Legacy

A commitment to the common good continued to guide the efforts of the Women's Service Club in subsequent decades. Despite financial challenges and an aging membership, the Club persisted in responding to Boston's evolving needs during the late-twentieth century and into the new millennium. Initial efforts to professionalize domestic workers, for example, transformed into programs that trained homemakers and home health aides who met growing labor demands.[16] The Club also developed exclusive programming for senior citizens and expanded educational instruction to offer computer lessons, Spanish courses, and ESL classes.[17]

Former clients and daughters of earlier leaders carried on the service of their forebears as they mentored other women and championed issues such as affordable housing and integration.[18] Familiar projects such as clothing and food drives endured as well.[19] Following a century of activity, the Women's Service Club of Boston remains dedicated to its mission of uplifting the city and its residents.

Contributed by: Mia Michael, Park Ranger

Footnotes

[1] Violet Showers Johnson, The Other Black Bostonians: West Indians in Boston, 1900-1950 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006), 6; Mark Schneider, Boston Confronts Jim Crow, 1890-1920 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997), 7-11; Adelaide Cromwell, The Other Brahmins: Boston’s Black Upper Class, 1750-1950 (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994), 49, 140; Lyda S. Peters, “Reclaiming the Narrative: Black Community Activism and Boston School Desegregation History, 1960-1975,” (PhD diss., Boston College, 2017), 52-58, 133-160; Stephan Thernstrom, The Other Bostonians: Poverty and Progress in the American Metropolis, 1880-1970 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), Chapter 8; Sarah Deutsch, Women and the City: Gender, Space, and Power in Boston, 1870-1940 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 19-21.

[2] Dorothy Salem, To Better Our World: Black Women in Organized Reform, 1890-1920 (Brooklyn: Carlson Publishing, 1990), Chapter 7; Cromwell, The Other Brahmins, Chapters 5 and 8.

[3] Women’s Service Club of Boston, “History: The Women’s Service Club of Boston, Inc.,” 100th Anniversary Hi-Tea Gala program, April 28, 2019; Women’s Service Club, “In Migrant Domestic Proposal,” Carton 31, Folder 443, Records of Boston Young Women's Christian Association, M220, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. Hereafter: SL.

[4] Anthony W. Neal, “Mary Evans Wilson was founding member of the Women’s Service Club, NAACP Boston Branch,” Bay State Banner, August 15, 2014; Anthony W. Neal, “Butler Roland Wilson: Humanitarian and Civil Rights Advocate,” Bay State Banner, September 26, 2012; Schneider, Boston Confronts Jim Crow, 136-137; Kaitlin Woods, “Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin,” Boston National Historical Park, https://www.nps.gov/people/josephine-st-pierre-ruffin.htm#_ftn5, accessed October 10, 2020.

[5] WSC, “In Migrant Domestic Proposal.”

[6] Ibid.; Women’s Service Club of Boston, Inc., “Chapter 5 Melnea Cass: The In-Migrant Program,” Folder 27, WSC; Women’s Service Club of Boston, Inc., “A Brief History of the Women’s Service Club,” National Committee on Household Employment Records, Series 003, Subseries 1, Box 20, Folder 25, National Archives for Black Women’s History, Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site, Landover, Maryland. Hereafter: NCHE Records, NABWH; Dorothy Parrish to Margaret M. Morris, July 11, 1968, NCHE Records, Series 003, Subseries 2, Box 7, Folder 10, NABWH; Melnea Agnes Cass, interview by Tahi L. Mottl, February 1, 1977, interview OH-31, transcript, p. 32, Black Women Oral History Project, Interviews, 1976-1981, SL, https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:45168257$1i. Hereafter: Cass transcript.

[7] Jo Holley “HubCaps,” Bay State Banner, February 29, 1968; “464 workshop plans ‘Follies,’ Bay State Banner, April 29, 1971.

[8] Lynda F. Dickson, “Toward a Broader Angle of Vision in Uncovering Women’s History: Black Women’s Clubs Revisited,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies 9, no. 2 (1987), 62-68; Barry Bluestone and Mary Huff Stevenson, The Boston Renaissance: Race, Space, and Economic Change in an American Metropolis (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000), 56-59; Daniel Golden and Donald Lowery, “Boston and the Postwar Racial Strain; Blacks and Whites in Boston: 1945-1982,” Boston Globe, September 27, 1982.

[9] “Club Woman,” The Chronicle, July 26, 1939; “Mrs. Rosa C. Brown Passes At Ninety,” The Guardian, November 24, 1954; “Full of Years and Service,” The Chronicle, November 27, 1954; Cass transcript, pp. 27-30, 38; Robert C. Hayden, Boston’s NAACP History, 1910-1982, Box 6, Folder 224, Muriel S. and Otto P. Snowden papers, M017, Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

[10] Boston National Historical Park, Boston African American National Historic Site, “Dr. Melnea Agnes Jones Cass,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/dr-melnea-agnes-jones-cass.htm, accessed October 10, 2020.

[11] The National Committee on Household Employment, “Final Report of the Experimental and Demonstration Projects,” October 1971, Box 58, Folder 1128, Papers of Esther Peterson, MC 450, SL; “Domestic Worker Gets Rough End of the Stick,” Bay State Banner, January 25, 1968; “In-Migrant Legislation To Be Resubmitted,” Bay State Banner, January 11, 1968; Mary King, “Household Work Parley to Weigh Critical Field,” Boston Globe, November 3, 1968; Pamela Cross, “Women’s service project reaches domestic workers,” Bay State Banner, November 22, 1973.

[12] “L.V. McAllister,” October 14, 1966, Folder 27, WSC; Movin’ Up: A Helping Hand,” (short version) directed by Rudy Hypolite and Jose Soares, original play written by Irma Askew (Boston, MA: Polite Productions and You Stubborn as a Mule Productions, 2006), DVD.

[13] Douglas D. Scherer, “H-1400 An Act Providing Protection For Domestic Employees Under The Labor Laws of the Commonwealth,” May 18, 1970, Folder 7, WSC; Otile McManus, “Household Help Upgrading Urged,” Boston Globe, November 17, 1970.

[14] Cass transcript, pp 113-114.

[15] Diane White, “New Hope for Domestics,” Boston Globe, December 13, 1972; Cheryl A. Landy, “1200 Mourn Death of Mrs. Cass,” Bay State Banner, December 21, 1978; WSC F9: “Address by Mrs. Maxine Mimms,” Fourth Annual Conference of Upgrading the Status of Household Employment, November 16, 1970, Folder 9, WSC; Natalicia Tracy, Tim Sieber, and Susan Moir ScD, “INVISIBLE NO MORE: Domestic Workers Organizing in Massachusetts and Beyond,” Labor Studies Faculty Publication Series, University of Massachusetts Boston 1, (2014), 16.

[16] “Who’s News,” Bay State Banner, January 18, 1979.

[17] “The Coordinated Elderly Service Program of The Women’s Service Club,” brochure, Folder 8, WSC; David Abel, “Age, changing society imperil the mission of women’s clubs,” Boston Globe, November 26, 2010; WSC, “History: The Women’s Service Club of Boston, Inc.”

[18] White, “New Hope for Domestics”: “Movin’ Up: A Helping Hand,” Hypolite, Soares, and Askew; “Activist Florence Hagins, 67, fought for affordable housing,” The Boston Banner, March 26, 2015; Lisa Wangsness, “Myra McAdoo, at 77; battler for housing rights in South End,” Boston Globe, February 12, 2007.

[19] WSC, “History: The Women’s Service Club of Boston, Inc.”