Last updated: January 13, 2025

Person

Dr. Melnea Agnes Jones Cass

Melnea Cass in 1969. Courtesy of Snell Library, Northeastern University.

"Melnea Cass Boulevard" winds through the heart of the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston as a tribute to one of the city's most cherished leaders: Melnea Cass.

A reader of the Boston Globe wrote to the newspaper in December 2003 with a pressing query about this distinguished roadway: "I drive over her boulevard every day on my way to work, but have no idea as to who Melnea Cass is or was. Please advise."[1] As a suffragist, clubwoman, and activist, Cass advocated for Boston's most disadvantaged inhabitants. She received many awards and well-deserved recognition for her tireless community service, though details about her life appear forgotten. In her activism, Cass collaborated across lines of race and class, gender and religion. She adamantly believed that everyday people could make a positive difference in others' lives.[2] Melnea Cass never ran for political office, but wielded power that expanded far beyond the realm of electoral politics and proved the potency of Black women's activism.

Domestic work and migration played a central role in Melnea Cass's early life and acquainted her with the hardships of the people she later served. Born in Richmond, Virginia in 1896, Cass and her family experienced racial oppression. Her mother labored as a domestic worker and her father as a janitor, limited to menial employment because of their race. Slavery intimately harmed their family, too. Cass' grandmother, Lizzie, had been enslaved from a young age in rural Virginia prior to the Civil War.

At age five, her parents decided to move their family to the North for better educational and employment opportunities. They joined the early wave of Black individuals and families who embarked on uncertain journeys, sparking what historians call the Great Migration. The family settled in Boston where their Aunt Ella Drew – also a domestic worker – lived.[3]

Cass undertook other migrations following the death of her mother around 1906. She and her sister moved to Newburyport, Massachusetts to attend grammar school and live under the care of their aunt’s employer. Later, Cass returned to Virginia to complete her secondary education at St. Francis de Sales Convent School. Besides taking general studies, Melnea Cass recalled, "…we did domestic work, when we learned to keep the house and all that, because mostly colored [sic] girls at that time were hired out as domestics." Like many other young Black girls, racism circumscribed Cass' education and employment opportunities. Nevertheless, she excelled, graduating as valedictorian of her class in 1914.[4]

Cass' experiences of racial and gender discrimination in Boston also determined her priorities as an activist. After returning to Boston, Melnea Cass discovered that many employers excluded women and people of color from certain jobs. To support herself, she used her training in household management and became a domestic worker on Cape Cod and in Boston for several years. Soon after her marriage to Marshall Cass in 1917, she ceased working outside the home and raised her three children. As the Great Depression unfolded in the 1930s, however, she had to return to domestic work to support her family.[5]

Melnea Cass connected her limited employment options to race and gender prejudice. As she recalled in an interview:

Well, in those days, of course, being Black, dear, affected every Black person getting any kind of job. Of course, you could get domestic work, because they always felt that Black people should do domestic work. But it was getting other kinds of jobs where the discrimination came in....Women could get all the work they wanted, domestic work….You could always make a living. But it wasn’t always what you wanted to do.[6]

Participation in civic and social organizations provided an avenue for Black women such as Cass to interact beyond work and serve their communities.[7] Her mother-in-law, Rosa Brown, introduced Cass to several organizations, including two Melnea Cass later led: the Boston branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (Boston NAACP) and the Women's Service Club (WSC). With Brown's encouragement, Cass also became a proponent of women's suffrage. After casting her first vote, Cass organized other Black women to do so as well.[8]

Cass' commitment to the disadvantaged did not end there. From the 1920s through the 1970s, Cass participated in a multitude of organizations at the local, state, and national levels.[9] For instance, she engaged in street protests against employment discrimination in Boston as part of William Monroe Trotter's National Equal Rights Association.[10] She also further advanced the cause of workers’ rights by co-founding a local chapter of A. Philip Randolph's Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.[11]

Cass later became the only female and community charter member of the anti-poverty community organization Action for Boston Community Development (ABCD). As a member of the Robert Gould Shaw House, a community center and settlement house, she co-created "Kindergarten Mothers" to provide day-care services for working women, the first of its kind in Boston's Black community. Cass adopted the group's motto as her maxim: "If we cannot do great things, we can do small things in a great way."[12] By the time she served as president of both the Boston NAACP (1961-1963) and the WSC (1962-1978), Cass was a bona fide community organizer.

Melnea Cass knew that voting rights meant little if women did not have access to fundamentals such as adequate wages and a safe workplace. In response, she organized on behalf of perhaps the most vulnerable workers in Boston: domestic employees. Unlike most other laborers in America, the federal government excluded domestic workers from protective legislation such as a guaranteed minimum wage wage and an eight-hour workday.[13] During the 1960s and 1970s, young migrant women of color from the South and Caribbean islands comprised a significant portion of Boston's household employees. Manipulative employment agencies offered empty promises of a better life in the North with high wages and educational opportunities. Workers often fell victim to wage theft, overwork, and other abuses, yet lacked recourse.

The Boston NAACP and WSC first learned of this exploitation under Cass' leadership and validated the gravity of domestic workers’ plight. Official investigations by the Boston NAACP continued after Cass' tenure as president ended in 1963 and resulted in the closure of rogue employment agencies. The Boston NAACP also earned the support of prominent clergy and politicians to pass state legislation in 1964 that mandated agency licensure and transparent interactions with domestic workers.[14]

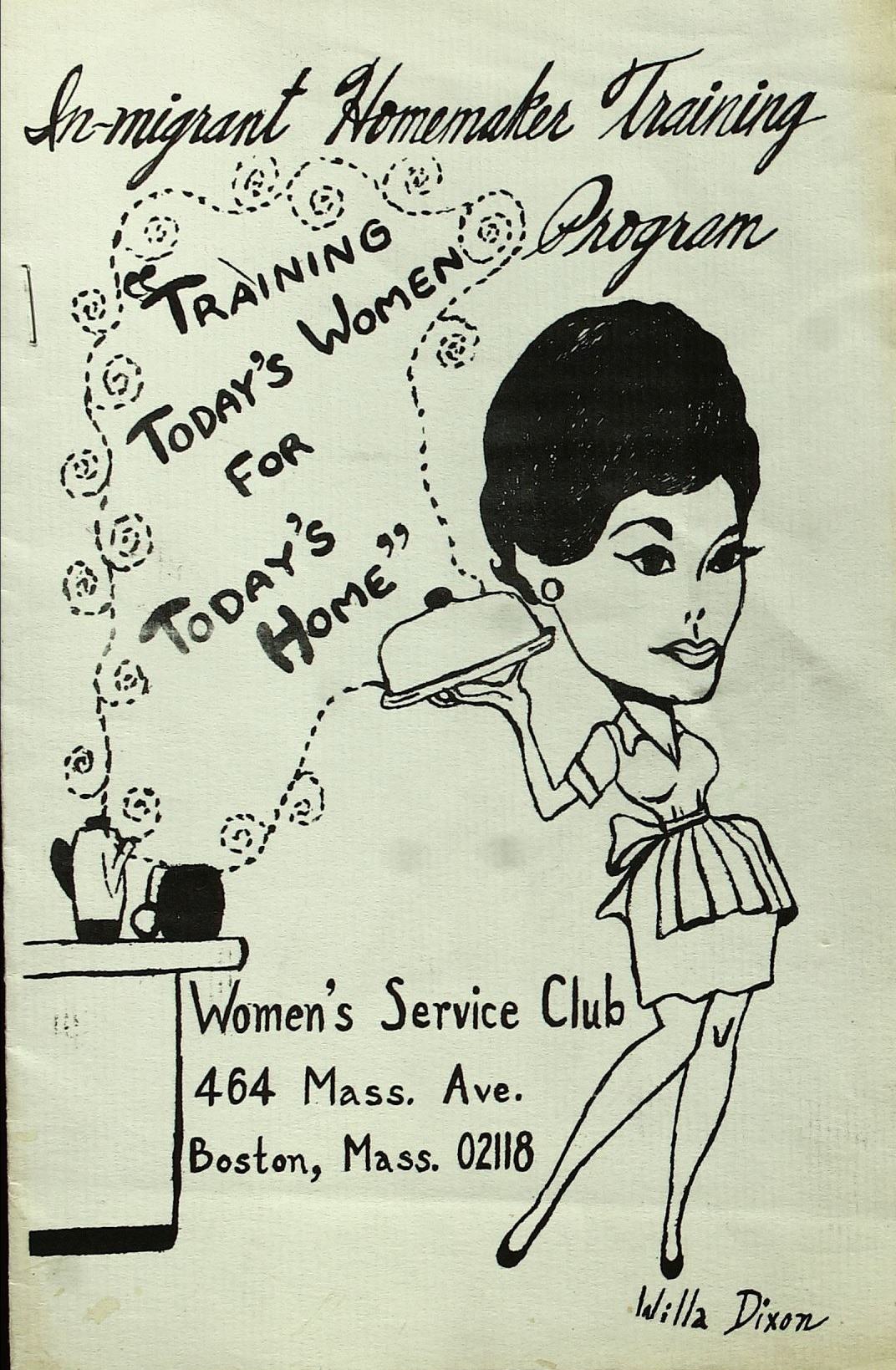

Federally-funded programs initiated by the WSC during the 1960s in collaboration with the National Committee on Household Employment helped domestic workers of multiple racial and ethnic backgrounds even more directly. By offering social services, professional training, and education about labor rights, these programs empowered workers to demand respect and fair treatment from their employers. Public conferences and a legislative campaign anchored by the WSC attracted inter-racial, cross-class, and bipartisan support. This work resulted in another concrete victory in 1970: Massachusetts' passage of the nation's first state-level minimum wage protections for domestic workers since the Great Depression. Over the following decade, the WSC's advocacy became a celebrated national model for other activists.[15]

Melnea Cass looked back on her life's work in 1977 and described the WSC's advocacy for domestic workers as "the best achievement yet that I have taken part in because it is helping so many people…"[16] This declaration is especially remarkable in light of her wide-ranging community service that attracted greater recognition: challenging discriminatory housing practices, combatting de facto segregation in Boston Public Schools, and championing the concerns of senior citizens. In time, Cass' efforts earned her honorary doctorates from prestigious universities and the affectionate title of "First Lady of Roxbury." Yet she remained a humble servant of the city's most vulnerable residents. Her efforts to prioritize their needs throughout the twentieth century extended women's political activity beyond the electoral sphere. Melnea Cass' legacy is not forgotten and continues to inspire domestic workers and activists in Boston and beyond.

Contributed by: Mia Michael, Park Ranger

Footnotes:

[1] Thomas F. Mulvoy Jr., “FYI,” Boston Globe, December 14, 2003.

[2] “Newton Cites Mrs. Cass,” Boston Globe, May 27, 1968.

[3] Melnea Agnes Cass, interview by Tahi L. Mottl, February 1, 1977, interview OH-31, transcript, pp. 1-6, Black Women Oral History Project, Interviews, 1976-1981, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:45168257$1i Hereafter: Cass transcript.

[4] Cass transcript, 1-10, 14-16, 33-34; Ruth Edmonds Hill, “Melnea Cass ‘First Lady of Roxbury,’” Vol 1 of Notable Black American Women, edited by Jessie Carney Smith (Detroit: Gale Research, 1992), 169-172.

[5] Cass transcript, 18-20, 51-52.

[6] Cass transcript, 53.

[7] Adelaide Cromwell, The Other Brahmins: Boston’s Black Upper Class 1750-1950 (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994), Chapters 5 and 8.

[8] Cass transcript, 26-32; Carmen Fields, “Obituaries: Melnea A. Cass, at 82 She was known as ‘First Lady of Roxbury,’” Boston Globe, December 17, 1978.

[9] For more information, see: Hill, “Melnea Cass ‘First Lady of Roxbury.’”

[10] Cass transcript, 27-29; Fields, “Obituaries: Melnea A. Cass”; Fred Hapgood, “Melnea Cass—the First Lady of Roxbury,” Boston Globe, May 13, 1973.

[11] Cass transcript, 55-56.

[12] Cass transcript, 35-39, 66-67, 82; Hapgood, “Melnea Cass – the First Lady of Roxbury.”; Patricia Miller King, “Melnea Cass,” in African American Lives, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 150.

[13] Premilla Nadasen, Household Workers Unite: The Untold Story of African American Women Who Built a Movement (Boston: Beacon Press, 2015), 125-127.

[14] “Domestic Worker Gets Rough End of the Stick,” Bay State Banner, January 25, 1968; Mary King, “Household Work Parley to Weigh Critical Field,” Boston Globe, November 3, 1968; Bryant Rollins, “Cardinal Aids NAACP Asks Job Agency Curbs,” Boston Globe, March 6, 1964; Press Release, Boston Branch N.A.A.C.P., 1964, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People records, 1842-1999, Part III, Box III: C61, Folder 3, Library of Congress, Washington D.C.; Tom Atkins to Melnea Cass, May 12, 1965, National Committee on Household Employment Records, Series 003, Subseries 1, Box 13, Folder 8, National Archives for Black Women’s History, Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site, Landover, Maryland.

[15] King, “Household Work Parley to Weigh Critical Field.”; Diane White, “New Hope for Domestics,” Boston Globe, December 13, 1972; Cheryl A. Landy, “1200 Mourn Death of Mrs. Cass,” Bay State Banner, December 21, 1978.

[16] Cass transcript, 114.