Last updated: January 6, 2026

Article

"Make the World Better": The Woman's Era Club of Boston

As these ladies are able and fearless advocates of woman suffrage, it may be expected that the Woman's Era Club will take the lead in educational work for the movement among colored women.

- The Woman's Journal, March 17, 1894[1]

Rare Books and Special Collections, Boston Public Library.

This earnest call, coming from the nationally recognized women's suffrage journal of the United States, placed an enormous responsibility on the Boston-based Woman's Era Club. While suffrage was not the primary goal of the club, members of this Black women's club rose to the challenge by actively engaging in the suffrage movement. They participated in suffrage events, joined local organizations, and published articles in support of the suffrage cause. Club members though went beyond advocating for suffrage by encouraging the enrichment of Black women, aiding the less fortunate and oppressed, and working to improve their communities. In fighting for suffrage and other causes dear to their hearts, the Woman's Era Club called for greater equality and justice both in Boston and throughout the country.

Beginnings

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Maria Baldwin, and about twenty other Black Boston women founded the Woman’s Era Club in 1893. These women saw a need for a women's club that better included Black women, and the Woman's Era Club provided them with the opportunity to discuss and address topics of interest specific to both their gender and race.[2]

During the first meeting of the Woman's Era Club, Ruffin's daughter Florida Ruffin Ridley, the corresponding secretary of the club, read a report that highlighted the community's need for a club to be "started and led by colored women," because there are "so many questions which, as colored women, we are called upon to answer."[3] The members of this new club accepted the responsibility of addressing the numerous issues that affected specifically the Black community, and, generally, humanity at large. The club's motto, "Help to make the world better," not only recalled the last words of White abolitionist and suffragist Lucy Stone, but it also emphasized members’ dedication to a variety of causes, including women’s suffrage.[4]

Participation in the Suffrage Movement

In 1894, a Boston Globe article mentioned that Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin brought women together in the Woman's Era club "to talk on woman’s suffrage."[5] Beyond this source, few external records recognized the involvement of the Woman's Era Club in the suffrage movement. However, numerous members publicly supported women’s suffrage, including Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Maria Baldwin, Eliza Gardner, Arianna Sparrow, and Florida Ruffin Ridley. These women participated in suffrage meetings and joined local suffrage organizations before, during, and after their time with the Woman's Era Club.

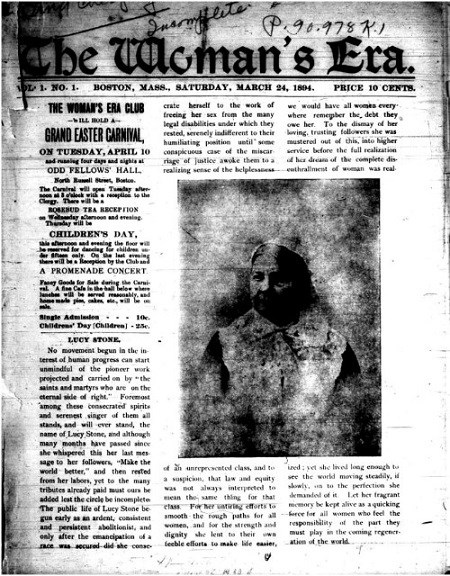

Similarly, The Woman's Era, the publication of the Woman's Era Club, voiced support for the suffrage movement. Established in 1894 by Ruffin and Ridley, The Woman's Era demonstrated that the club's members actively participated in the suffrage discussion. The journal published notices of local suffrage events, updates on legislative movement, and pro-suffrage editorials. The editorials, likely written by either Ruffin and Ridley, criticized opponents of women’s suffrage and expressed hope for future political representation. In a particularly scathing rebuttal to anti-suffragists, an editorial countered, "The weak effusive arguments against suffrage can have but one effect on the indifferent, and that is to turn them into suffragists."[6] In supporting suffrage, the editors specifically encouraged Black women to support the movement, insisting, "This class [of women] has everything to gain and nothing to lose by endorsing the woman suffrage movement."[7]

Bettering the Community

While members of the Woman's Era Club supported women’s suffrage and wrote in favor of the movement in The Woman's Era, suffrage occupied only a small percentage of the efforts and interests of the club and journal. Holding at least two meetings a month, the Woman's Era Club gathered to discuss civics, domestic science, literature, public improvements, or issues that directly affected the Black community.[8] The club also worked within its community, organizing fundraising events for local institutions, including the Home for Aged Colored Women and St. Monica's Home for Sick and Colored Women and Children, and raising money for scholarships for young Black women aspiring for higher education.[9]

Most importantly, members of the club actively participated in Boston's conversations on racism and discrimination. They wrote and distributed pamphlets advocating against lynching and formed a committee with leading local Black activists and political leaders to bring awareness to the lynching crisis in the United States.[10] Through these causes, club members sought to organize women to effectively improve their own lives and the lives of people in their communities.

The Woman's Era Journal

In an early publication of The Woman's Era, the editors noted the need for a paper written primarily by and for women of color. This publication hoped to fill the void and give a voice to not only the Woman's Era Club, but to Black women nationwide, declaring, "We are about old enough to speak for ourselves."[11] The journal gained contributors from around the country, eventually serving as the main publication for the Black women's club movement. The Era included updates on local club activities and sections on literature, health and beauty, and news on issues relevant to Black Americans, including poverty, education, and discrimination. Compared to these topics, suffrage only took up a few of the Era's pages.

This publication served as the platform through which Black women could present a public voice. The Woman's Era aimed "to give a knowledge of the aims and works of each [organization] to help in every way their growth and advancement and bring the colored women together in great and powerful organization for the growth and progress of the race."[12]

Members of the Woman's Era Club showed an interest in and supported the suffrage movement in Boston. However, women’s suffrage was not its primary objective. The club and the women behind the club had larger goals, including the self-improvement of Black women and the general betterment of African Americans. They believed in working for equality and justice on a larger scale, for "humanity and humanity’s interests."[13] The women of the Woman's Era Club had an expansive vision, one that went far beyond one issue or one group of people.

[1] "With Women’s Clubs," Woman's Journal 25, no. 11 (March 17, 1894), Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, accessed February 24, 2020, https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:49673169$89i

[2] "Mrs. Ruffin and the Woman's Era Club of Boston," Los Angeles Herald, April 06, 1902.

[3] "Boston: The Woman’s Era Club," The Woman's Era 1, no. 1 (March, 1894).

[4] "Boston: The Woman’s Era Club," The Woman's Era 1, no. 1 (March, 1894).

[5] "Sets in Colored Society," The Boston Globe, July 22, 1894.

[6] "Woman's Place," The Woman's Era 1, no. 6 (September, 1894).

[7] "Colored Women and Suffrage," The Woman's Era 2, no. 7 (November, 1895).

[8] "Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin," Sketches of Representative Women of New England, ed. Julia Ward Howe (Boston: New England Historical Publishing Company, 1904): 335-339; Mary Church Terrell Papers: National Association of Colored Women, 1897 to 1962; Holograph report; 1899 Convention. 1899. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss425490293/.

[9] See The Woman's Era and Mary Church Terrell Papers: National Association of Colored Women, 1897 to 1962; Holograph report; 1899 Convention. 1899. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mss425490293/.

[10] These leaders included Clement Morgan, Butler Wilson, and Emory Morris. See Teresa Blue Holden, "'Earnest Women Can Do Anything:' The Public Career of Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, 1842-1904," (Phd dissertation, Saint Louis University, 2005) and The Woman's Era 1, no. 4 (July, 1894).

[11] The Woman's Era 2, no. 1 (April, 1895).

[12] "Our Women's Clubs," The Woman's Era 1, no. 2 (May, 1894).

[13] "Boston: The Woman's Era Club," The Woman’s Era 1, no. 1 (March, 1894).

Tags

- boston national historical park

- boston african american national historic site

- women's history

- women's rights

- african american history

- african american women

- 19th amendment

- massachusetts

- suffrage

- civil rights

- boston

- black womanhood series

- shaping the political landscape

- women and politics

- women leaders