Last updated: May 29, 2022

Person

Sojourner Truth

Sojourner Truth was born Isabella Baumfree in 1797 in Ulster County, New York, the daughter of James and Elizabeth Baumfree. Together with her parents, she spent her childhood enslaved on the estate of Johannes, then later Charles, Hardenbergh. Enslaved by Dutch settlers, Dutch was her first language. When she was nine years old, she was sold away from her parents to John Neely near Kingston, New York. He purchased her and a flock of sheep for $100. Baumfree remained at John Neely’s until 1808, when she was sold to tavern keeper Martinus Schryver of Port Ewen, New York, where she stayed for 18 months. In 1810, she was sold to John Dumont, of West Park, New York. She remained his property until 1826, when she escaped to freedom.

While at the Dumonts, Baumfree experienced tension and harassment from John’s wife, Elizabeth and rape by John. In 1815 Baumfree met and fell in love with Robert, an enslaved man from a neighboring farm. Robert’s owner forbade the relationship, and beat Robert to death for meeting Baumfree against his wishes. Some years later, Baumfree married an older enslaved man named Thomas. She had had two children prior to Thomas - her first child, James, died in childhood. Her second, Diana, was the result of a rape by John Dumont. She had her last three children, Peter, Elizabeth, and Sophia, with Thomas.

In 1799, New York State passed a law for gradual abolition of slavery. After July 4, 1799, children born to enslaved women were, by legal definition, free, but required to work for their mother’s owner until they were in their twenties (28 for males, and 25 for females). Those born before July 4, 1799 were redefined by law as indentured servants. In reality, they continued to be enslaved for life. An 1817 law declared that all slaves in the State born before July 4, 1799 would become free on July 4, 1827. John Dumont promised to emancipate Baumfree before this final date of emancipation. In 1826, he changed his mind. So, before the year ended, Baumfree freed herself and her infant daughter Sophia. She was not able to bring the rest of her family with her, and would later work to emancipate Peter after Dumont sold him south to Alabama in defiance of the law. Baumfree and her daughter found refuge at the home of Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen in New Paltz, New York. To keep her safe, the Van Wagenens paid Dumont $20 for her labor until emancipation day, July 4, 1827.

While staying with the Van Wagenens, Baumfree’s focus shifted to finding her son Peter. With the assistance of her hosts, Baumfree brought her son’s case to a legal hearing at court. The drawn out process of finding Peter and fighting to bring him back home ended in 1828, when the court ruled in her favor and Peter returned to New York.

It was while with the Van Wagenens that Baumfree experienced a religious awakening, becoming a devout Christian. In 1829, she and Peter left New Paltz and moved to New York City. Baumfree worked as a housekeeper in the city, and at one point was accused of poisoning and stealing from one of her employers. She was acquitted of both charges. In 1839, Peter took a job on a whaling ship. Although Baumfree received letters from her son during his journeys, when the ship returned to New York in 1842, Peter was not on board. She never heard from him again.

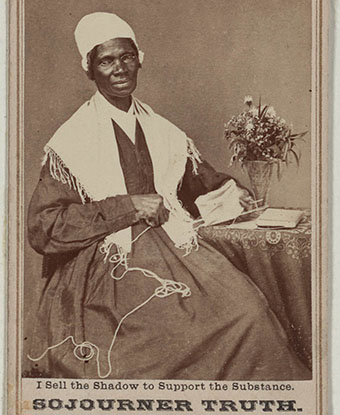

In 1843, Baumfree became a Methodist. Called by God to leave the city and “testify the hope that was in her” across the countryside, she took the name Sojourner Truth and began touring the country speaking against slavery. In 1844, she moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, and joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry.[1] Founded by abolitionists, this utopian community was a stop on the Underground Railroad; it’s members supported women’s rights, religious tolerance, and pacifism. It was in Northampton that she met William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass. After the Association disbanded in 1846, Truth remained in western Massachusetts and began dictating her memoirs to her friend Olive Gilbert. In 1850 her book, The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: a Northern Slave was published by Garrison; she bought a house in Northampton, and spoke at the first National Women’s Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. She paid off her home just three years later, in part by selling photographs of herself captioned, “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”

In May 1851, she attended the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, where she delivered her speech “Ain’t I a Woman?”, one of the most famous speeches on African American and women’s rights in American history.[2] For most of her remaining life, Truth continued to travel the United States to speak on matters relating to the rights of African Americans and women, including the right to vote.

In 1857, Truth moved to Harmonia, Michigan, where she had friends and where her daughter Elizabeth lived. She later moved to Battle Creek. During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit African American men for the Union Army. Her grandson, James Caldwell, enlisted in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. In 1864, she worked for the National Freedmen’s Relief Association in Washington, D.C., where she met President Abraham Lincoln. While in Washington, she traveled on public streetcars in support of their desegregation.

Truth continued to advocate and lobby pressure for the needs of African Americans. Starting in 1870, she advocated to secure land grants from the federal government for former enslaved people, which was an unsuccessful effort. As part of this work, she met President Ulysses S. Grant in the White House.[3] In 1872, she returned to Battle Creek and worked on Grant’s re-election campaign. She went to the polls on Election Day to vote but was turned away.

Although her health was in its decline, she continued to travel and speak. She died in her Battle Creek home on November 26, 1883 at age 86. She was buried in Battle Creek’s Oak Hill Cemetery. In her life, she tirelessly advocated for the rights of African Americans, women, and for numerous reform causes including prison reform and against capital punishment. She is memorialized in countless art works, murals, and statues. She provided the namesake for the 1997 NASA Mars Pathfinder robot Sojourner, and for the asteroid 249521 Truth. In 2009, Truth became the first Black woman memorialized with a bust in the U.S. Capitol.[4]

Notes:

[1] The only surviving building of the Northampton Association of Education and Industry is Ross Farm at 123 Meadow Street, Northampton, Massachusetts. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 8, 2008.

[2] Sojourner Truth spoke extemporaneously at the meeting in Akron; she did not have a written speech to read from. Therefore, her words survive as written by others. There are many variations of what Truth said; the first record of her full speech, published within a month of her giving it, does not include the phrase, “Ain’t I a Woman.” Twelve years later, in 1863, another version was published by Frances Dana Barker Gage, a suffragist and abolitionist who worked with Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others. In her version, Truth’s words have the stereotypical characteristics of Southern slaves (even though Truth grew up in New York speaking Dutch), included the phrase “Ain’t I a Woman,” and included embellishments about her life. It is Gage’s version of Truth’s speech, which was republished in 1875, 1881, and 1889, that has become the version most people are familiar with.

[3] The White House was designated a National Historic Landmark on December 19, 1960.

[4] The United States Capitol building was designated a National Historic Landmark on December 19, 1960.