Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 15, No. 1, Spring 2023.

Article

Wind Cave Paleontological Resource Inventory

Theodore Herring

Wind Cave National Park

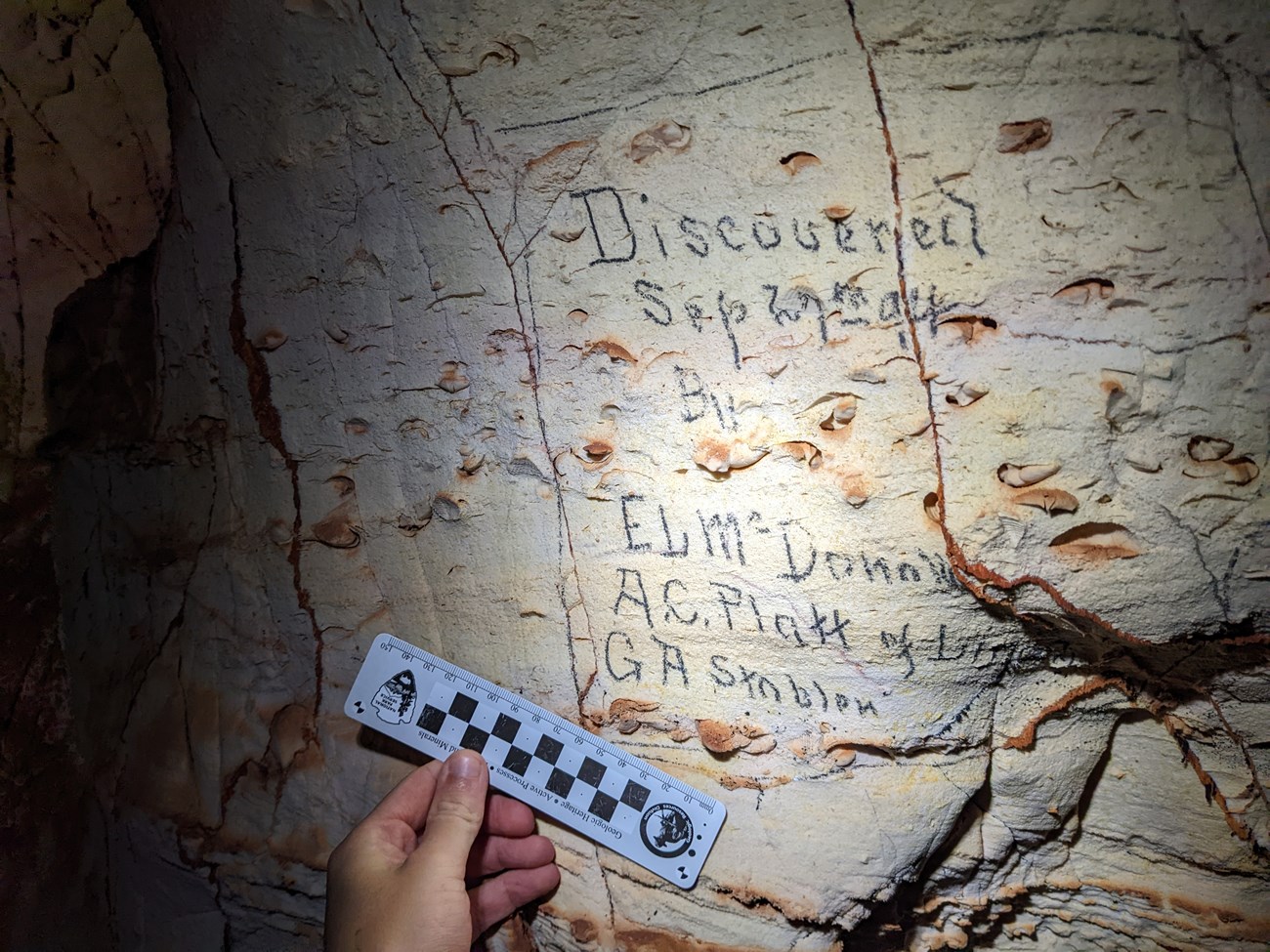

NPS Photo by Ben Shreves.

Introduction and Objectives

Wind Cave National Park (WICA) is home to Wind Cave, the third longest cave system in the United States and seventh longest in the world. WICA also functions as a geological microcosm of the Black Hills, with formations dating from Precambrian to Late Quaternary. Several of these formations are fossiliferous, and many fossil localities have been discovered both within Wind Cave and at surface exposures.

Paleontology at WICA has an extensive history: explorers have been documenting fossils in the cave since 1891. However, the paleontological resources of the park greatly expanded in the 1980s, when WICA staff began a partnership with paleontologists from the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. Since then, thousands of fossil specimens have been excavated and collected from the park, leading to a greater understanding of the geological, ecological, and environmental history of the southern Black Hills area. To help inform further research and protection of WICA’s resources, a paleontological resource project was initiated to provide baseline information to WICA staff and potential researchers. Components of this resource project included assessing historical fossil localities throughout the park, documenting new paleontological localities, assessing fossil collections, conducting a literature review on relevant paleontological research pertaining to the park, and interviewing current and past WICA staff about information on the park’s fossils, plans for fossil management, and recommendations for interpretation.

Below I highlight some of the most intriguing fossil localities identified within the park, and new information discovered as part of the resource inventory project.

Madison Limestone

The Madison Limestone, also known as Pahasapa Limestone, formed in the Early Mississippian and is the foundation of WICA’s caves. Over the past tens of millions of years, groundwater has cyclically eroded voids in buried layers of Madison Limestone throughout the park, forming hundreds of miles of cave passages which are still being surveyed. These caverns contain several remarkable fossil beds, primarily featuring brachiopods; some of these fossil beds include hundreds of molds and casts embedded within the rock. Occasionally, other fossils can be found in these layers, such as gastropods, crinoids, sponges, and worm burrows. Brachiopod fossils are the only fossils in the park that are accessible to the public: they can be seen on the Fairgrounds Tour Route, which is offered year-round to visitors.

One notable brachiopod locality was newly documented as part of the resource inventory project. This locality features hundreds of brachiopods concentrated in a band stretching around the cave room. Some of these brachiopods have graffiti written over them, indicating early cave explorer Elmer McDonald and two of his companions first discovered the room in 1894. Additionally, a few brachiopods have been recrystallized in calcite, a unique feature not often found in the cave.

Minnelusa Formation

The Minnelusa Formation is a geologic formation formed during the Pennsylvanian subperiod. Various fossils, such as foraminifera, brachiopods, bivalves, and gastropods have been discovered in the Minnelusa Formation within the park. The Minnelusa fossils most of interest to the paleontological resource inventory are conodonts, which were discovered in the park during the early 2000s by a USGS geologist but have since not been extensively documented or studied. Over a dozen conodont specimens were collected and photographed in November 2022 during the resource inventory project and plans to identify them are currently underway. A species-level identification of these conodonts could help inform a more precise dating of the rock formation.

White River Group

The White River Group, composed of the Chadron and Brule Formations, is an Eocene to Oligocene geologic group that has multiple surface exposures in the park, many of which are productive fossil sites. Seven of the White River Group localities were originally discovered in the 1980s by retired park biologist Richard Klukas, and more than thirty localities have been documented to date. One of these localities, the Centennial Site, was discovered in the park’s centennial year, 2003. This site was made famous by the discovery of a skull belonging to Subhyracodon, a small, hornless rhinoceros. Other fossils found at the White River Group localities include hackberry seeds and various gastropods, turtles, lizards, and mammals. These fossils indicate the area used to be a dry warm grassland during the Oligocene, and ecological reconstructions interestingly do not strongly differ from those found at Badlands National Park, despite the altitudinal differences of the two locations.

The White River Group localities were resurveyed for the paleontological resource inventory. Most of these sites have already been diligently excavated, and thus have not revealed many new fossils. One of the fossils discovered in October 2022 was the lower jaw of Leptomeryx, a small, deer-like ruminant that lived during the Eocene and Oligocene. WICA staff plans to cyclically monitor these fossil localities in case any new fossils erode out of the sediment in the coming years.

Late Quaternary

WICA is home to several caves and rock shelters that have preserved fossils from throughout the Pleistocene and Holocene. There are a few vertebrate localities within Wind Cave, which indicate possible locations of paleo-entrances that have since filled. Other notable Quaternary localities include Salamander Cave, Beaver Creek Shelter, and Graveyard Cave. Salamander Cave features mammalian fossils stretching back to at least 250,000 years. Beaver Creek Shelter and Graveyard Cave are both informative Holocene localities that have yielded thousands of bones from a diverse assortment of mammals, birds, frogs, reptiles, and fish.

One Quaternary locality that is currently under active excavation is Persistence Cave. Persistence Cave was originally discovered in 2003 by WICA physical scientist Marc Ohms, and excavation of the cave has been underway since 2008. Persistence Cave is of particular interest because it is hypothesized to connect to Wind Cave, though the connection has not yet been surveyed. The most recent excavation effort took place in November 2022, when several volunteers traveled to WICA for a weekend to help remove dirt and drill through rock filling the cave. Excavation has revealed a plethora of vertebrate bones from the Pleistocene and Holocene. One specimen of interest is a pine marten, which is estimated to have died at least 11,000 years ago based on carbon dating. The pine marten is not currently found in the Black Hills area, so this find indicates potential local faunal shifts during the late Pleistocene and throughout the Holocene. The Persistence Cave excavation has been made possible because of a partnership with the Mammoth Site, whose staff have offered to collect, sift, and store all fossils collected from Persistence Cave.

A surface Quaternary locality that was discovered in spring of 2022 is a collapsed pit feature. Near a river drainage, a 6’ diameter, 3’-deep sinkhole recently formed, which revealed the ilium of an indeterminate ungulate that had not yet mineralized. The pit grew over the following months, as the sides began to erode away. This collapsed pit is the only such feature yet discovered in the area. Park staff will continue monitoring the pit and will keep on the lookout for other such features that may reveal more fossils. In nearby drainages, several bones belonging to bison have been discovered in the past decade.

WICA staff will continue to cyclically monitor all cave and fossil sites in future years, as well as survey and excavate cave rooms in search of new fossil discoveries. A report based on the field inventory is being finalized at this time, and a public version is expected to be ready later this year.

Related Links

-

Wind Cave National Park, South Dakota—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home] [npshistory.com]

Last updated: March 22, 2023