Part of a series of articles titled The Williwaw Newsletter.

Article

Williwaw October-November-December 2020

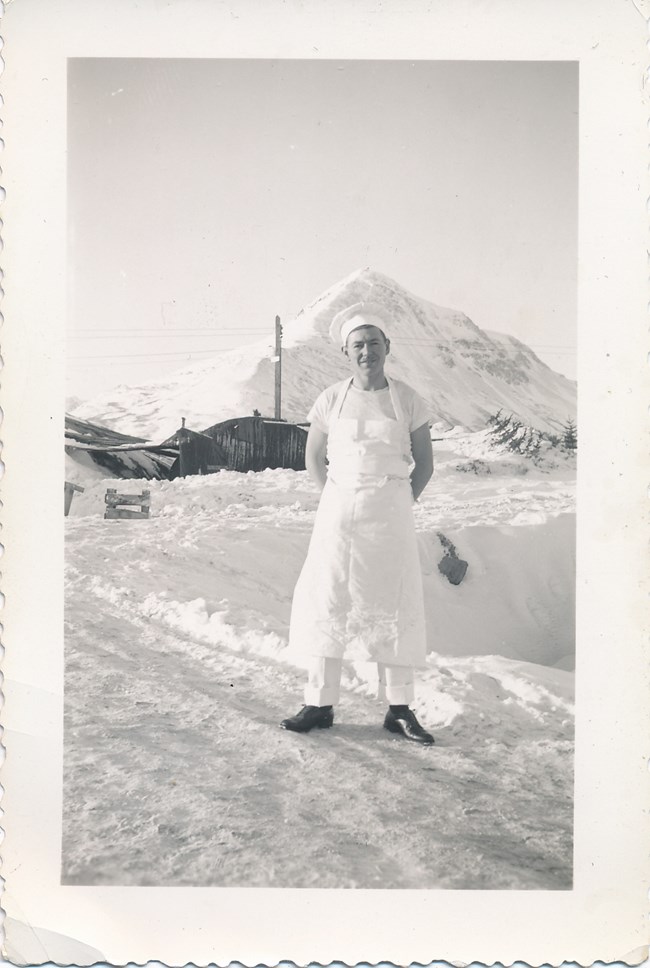

Courtesy of Stephanie Johnson Dixon, from the collection of Robert T. Johnson, 206th Coast Artillery Band

Holiday Issue

Going through the holiday season can be challenging even under normal circumstances. The planning, traveling, cooking, and making sure you have just the right present for everyone on the list can all add up to serious holiday stress and fatigue. We are sure that this year none of us would mind doing any of those things for the chance to be with our family and friends as we enter the long nights of winter. Some people even put up their trees before Thanksgiving and have decorated for the season. No judgement here. This year has been challenging in ways we haven’t experienced in quite some time and adding some cheery decorations could be just the right medicine. In this edition of The Williwaw, we will look at what helps us remain grounded in troubled times. From GIs in mess halls to the Unangax̂ who were taken prisoner by the Japanese, we will explore the role of food and traditions. We will also revisit a message delivered in-person by President Franklin Roosevelt who provided the troops some optimism in 1944.

As always, we encourage readers to write in to let us know how we are doing and to offer their own stories.

We wish you all a happy and safe holiday season. Be well.

--Karen Abel, Joshua Bell, and Rachel Mason, editors of the Williwaw

Centenarians Corner

Henry Barba, Arkansas National Guard, 107

Allan Seroll, US Army Signal Corps, 104

James Elsner, US Army Air Force, 101

Taps

US Army

Robert G. Leanna, 92, of Amasa, Michigan

Albert Rayle, 96, of Continental, Ohio

Martin J. Fahncke, 101, of Celina, Ohio

US Navy

Duane Keeler, 84, of Concord, New Hampshire

Milton Nolan Kassel, 97, of Savanah, Georgia

Richard H. Dodds, 95, of Youngstown, Ohio

Frederick Norman “Red” Lonberg, 93, of Fleming Island, Florida

Myron C. Knauff, 101, of Valparaiso, Indiana

US Coast Guard

Robert “Bob” Maurice Tilley, 95, of Butte, Montana

Courtesy of Karen Abel, granddaughter of Bob (P/O Robert Lynch)

Courtesy of Karen Abel, granddaughter of Bob (P/O Robert Lynch)

Christmas 1943, from England

By Karen Abel

"Dear Bob & Eileen,

How goes things with you? I am doing fine. Gee- these Spits are a real aircraft.

We just came back from a 48-boy did we get goosed. Sure had fun-and you can't beat fun- Life is good.

Hope you manage to get home for Xmas.

How is instructing going? Are you going to quit smoking Eileen, if you go home at Xmas?

Best of Luck, Ed."

Ed Merkley was an Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) fighter pilot with 111(F) squadron stationed in the Aleutians from June 1942 to July 1943. When his squadron returned to Canada he was posted overseas to Royal Air Force No. 57 Operational Training Unit. This was one of the last Christmas cards he would write and it was to my grandfather, P/O Robert Lynch. Ed died a few days later when another Spitfire collided with his over Eschott, Northumberland, England.

You can tell the type of character Ed must have been, “Life is good” he writes as he has just been sent to battle. Life is good…. It is comforting that these were his last sentiments and it inspires me to embody this spirit as well, especially this year!

Merry Christmas and a blessed New Year to All!

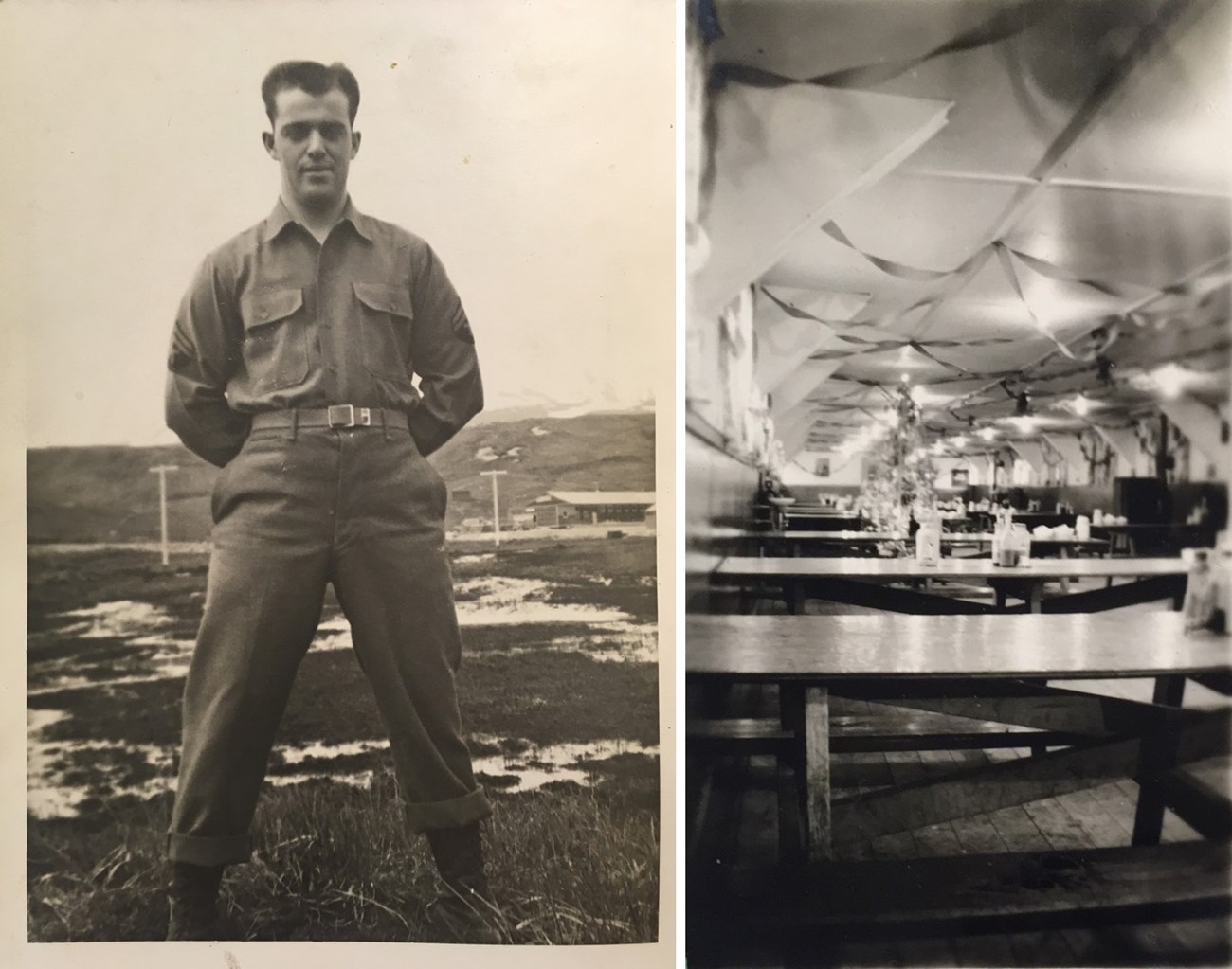

Courtesy of Stephanie Johnson Dixon, from the collection of Robert T. Johnson, 206th Coast Artillery Band

(Not) Home for the Holidays

By Joshua Bell

For GIs deployed around the globe during the war, the holidays were usually accompanied by unwelcome cases of homesickness. The uncertain times, not knowing when the war would be over, sharpened the focus on being separated from family and friends. As the world went through its darkest hours, it would have been easy to loosen a grip on hope and allow optimism to fade.

Released in 1941, White Christmas by Irving Berlin was not a hit. Within the year, however, it entrenched itself as a classic. The following year, American servicemen stationed in far-off places from Africa and the South Pacific to the outpost at Dutch Harbor, Alaska, listened as Bing Crosby sang another holiday staple, "I’ll Be Home for Christmas." A few years later, in 1944, when that song was distributed by the War Department on V-discs, Yank Magazine said that Crosby accomplished more for military morale than anyone else of that era. Just saying the names of those songs can make one feel nostalgic.

Although thousands of miles from where they rather would have been, soldiers, sailors, and Marines did what they became famous for – they made the best of a bad situation. Cpl. Allan Seroll of the Army Signal Corps and veteran of the Battle for Attu shared a story that captures this spirit. As a newly married man, he joined the Army in 1942 and spent the next four Thanksgivings away from home. He spoke about the excitement of a special shipment to the Aleutian Islands around the holiday season and disappointment when things didn’t work out as planned. You can watch his story of two very different Thanksgivings away from home on AlaskaNPS's YouTube channel.

Pfc. Vincent Bell, of the 58th Fighter Control Squadron, 11th Army Air Force captured that longing to be home again in a letter to his favorite aunt while he was at basic training before deploying to Attu. Presents, and particularly, homemade treats were prized by GIs. They were so prized, not just because a steady menu of Army cooking became monotonous – although Pfc. Bell never complained about the Army chow – but they were a taste of home. His letter is read by his grandson, former park ranger and co-editor of the Williwaw, Joshua Bell. Watch this 3-minute video on AlaskaNPS's YouTube channel.

What’s for Chow?

Food memories have the power to transport us far away from whatever is immediately in front of us. And although we might not be cooking for an army this year, having a good pie recipe on hand in case you need to next year might be useful. These recipes and instructions are brought to you directly from The Army Cook, TM 10-405, without alteration. While the pies might not ship well, the gingerbread should.

Courtesy of Albert King

A Warm Kitchen in the Winter

By Joshua Bell

Albert R. King hailed from the small coastal city of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Like most kids from his generation, he enjoyed playing baseball with his friends. But instead of playing on a grassy diamond, he and his friends played in the middle of the street. When the United States entered the war, King and his brother George were both drafted into military service in the summer of 1942. Unlike most young men processed at Fort Devens, King was not reassigned elsewhere. His experience working in the kitchen at Saint Luke’s Hospital earned him a ticket to the mess at Fort Devens. Not far from home, he was able to visit family during his free time. He was soon reassigned to the kitchens at Camp Edwards on Cape Cod, slightly closer to home. His assignment to the kitchen also came with the added benefit of deferring his basic training.

Military necessity soon caught up to King, and he was sent to Seattle, Washington. In his first big trip far away from home, he later recalled that, “Everything was so beautiful there. And they had, I can remember they had slot machines, and you put a nickel in it and you'd get an apple. And the apple, oh they were so delicious, oh man were they delicious!” It was there that he finally completed his basic training before being assigned to the 278th Coast Artillery and deployed to Adak.

As winter settled in the islands, weather howled as only an Aleutian Island winter can. King, however, was pleased with his assignment in the warm kitchens. He recalled, “I didn’t have to get out like the other guys did. Imagine how cold it is out there, and those guys out there, training in the snow. It must, it was rough for those fellows. And they were out there, and lots of times the electric lines would break, and they would be out there in the cold fixing them. It was rough, pretty rough out there.” The cooks not only kept warm in the kitchens, but they also kept warm in their barracks by taking pots and pans filled with water and placing them on the coal stoves in their Quonset huts. The 0430 wake-up calls came early, but being warm was worth it.

Eggs, toast, and hotcakes were popular dishes for breakfast. King and his team gained the favor of the officers on the island. Instead of taking meals in the officer's mess, they would eat with the enlisted men. “We had good food, you know. And I always gave anybody who wanted seconds, I'd give it to them, you know. Because I figured, the heck, these guys are here, they're doing their job, and they should be, eat whatever they want. And how much they want to eat, you know!” Meatloaf, stew, roast beef, pot roast, and pork chops were among the most popular dishes. Read a copy of the baseline recipe for meatloaf. What King did to make it a favorite, though, is still a secret.

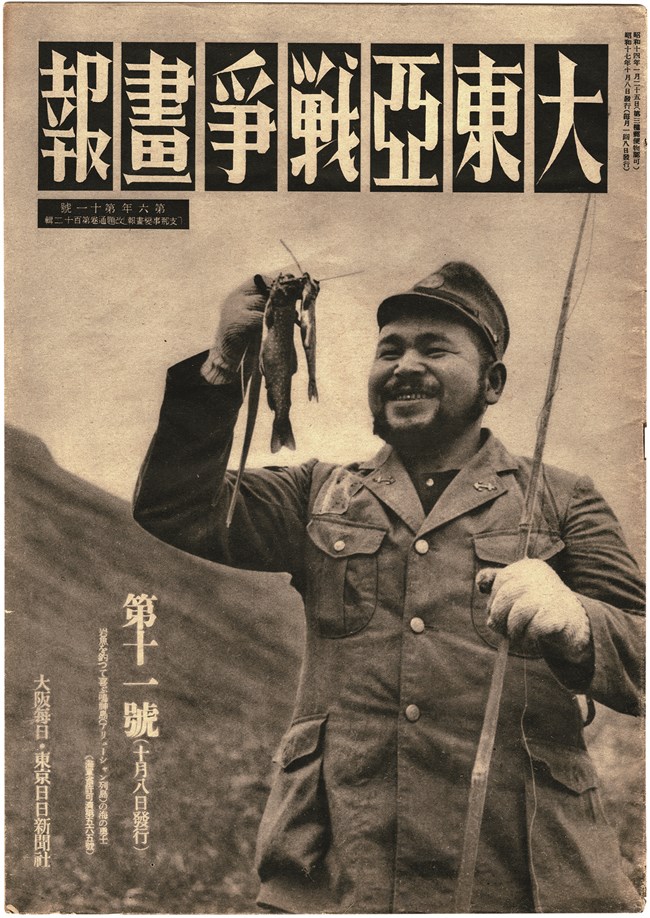

Daitoa senso gaho, October 8, 1942

Food for the Japanese Soldier

By Rachel Mason

Japanese soldiers were less well fed than the American troops. The wartime food shortage in Japan was reflected in the meager portions given to the military. The soldiers were expected to be as self-sufficient as possible, and looked for ways to supplement their diet in the Aleutians, especially with fish. According to an article about the Japanese soldiers on Kiska, some of the soldiers were quite successful:

The garrison dispatched to the Alaska post was from Northern Japan, accustomed to and prepared for a climate much like home. The abundant seafood supplied the men with unlimited delicacies like urchin eggs. When they returned to strictly rationed Japan, they were accused of having grown fat (Dunham 2010).

Other Japanese soldiers did not eat so well. During the Battle of Attu, the Japanese were cut off from food and other supplies from outside. On May 28, 1943, as the Battle of Attu was coming to its grisly end, Japanese doctor Paul Tatsuguchi wrote in his diary:

The remaining ration is for only two days…Ate half-fried thistle. It is the first time I have eaten something fresh in six months. It is a delicacy” (Obmascik 2019:134).

The next day, after a final, hopeless charge, all but a few of the remaining Japanese soldiers committed suicide.

Charles House: Living Off the Land

By Rachel Mason

Charles House, one of 12 American Naval Weathermen stationed on Kiska Island when the Japanese invaded in June 1942, was the only one to avoid capture. He lived alone on the island for 48 days, foraging for food and hiding in a cave. In a letter written after the war to his Commander, he said, “The only thing available for food was limited vegetation; tundra grass, wild celery, and lupine bulbs. An old fur trapper that I had met at Dutch Harbor had told me ‘There is nothing poisonous growing in the Aleutian Islands’, so I decided to start eating the vegetation.” He also ate angle worms he collected at a nearby stream, although he found them a little bitter. On the 48th day, he decided surrender was his only chance for survival. He struggled to the Japanese encampment and surrendered, waving his underclothes as a white flag. He weighed only 80 pounds when he surrendered. He survived as a POW and returned to America in 1945.

NPS/ Lake Clark National Park and Preserve

Food for Evacuees to Southeast Alaska

By Rachel Mason

After the bombing of Dutch Harbor/Unalaska, the U.S. government decided to evacuate the indigenous residents of the Aleutian Islands to Southeast Alaska. The Unangax̂ who were suddenly ordered to board boats were given very little time, in some cases only an hour, to pack for the trip. They were unable to bring any stores of food with them. On the boat, they were offered Western-style foods, a new experience for some of the Unangax̂. Irene Makarin, interviewed in 2004, was a young girl when her family was evacuated from Biorka and taken to Southeast Alaska. She remembered her shock at being offered cereal for breakfast instead of the boiled fish she usually ate. She said:

They tried to let me eat, I wouldn’t eat anything! Just cry! My daddy come over. “You better eat something.” He talked Aleut to me. I turned around and told my dad, “I want my fish, boiled fish!” [Laughs] “So you can’t have boiled fish. You got to eat.” I wouldn’t eat. He have a hard time. All the Biorka kids, they have a hard time to eat breakfast. (Makarin 2004)

After the Unangax̂ had been settled in relocation camps in Southeast Alaska, their diet continued to be quite different from the dried fish, seal meat and shellfish they were accustomed to eating at home. They were given canned food, but they missed the familiar foods of the Aleutian Islands. The evacuees lacked weapons and gear to hunt and fish for their own food. The Atka residents relocated to Killisnoo remembered visits from Tlingit people living in nearby Angoon, who shared salmon and venison with them and lent them boats to catch their own fish.

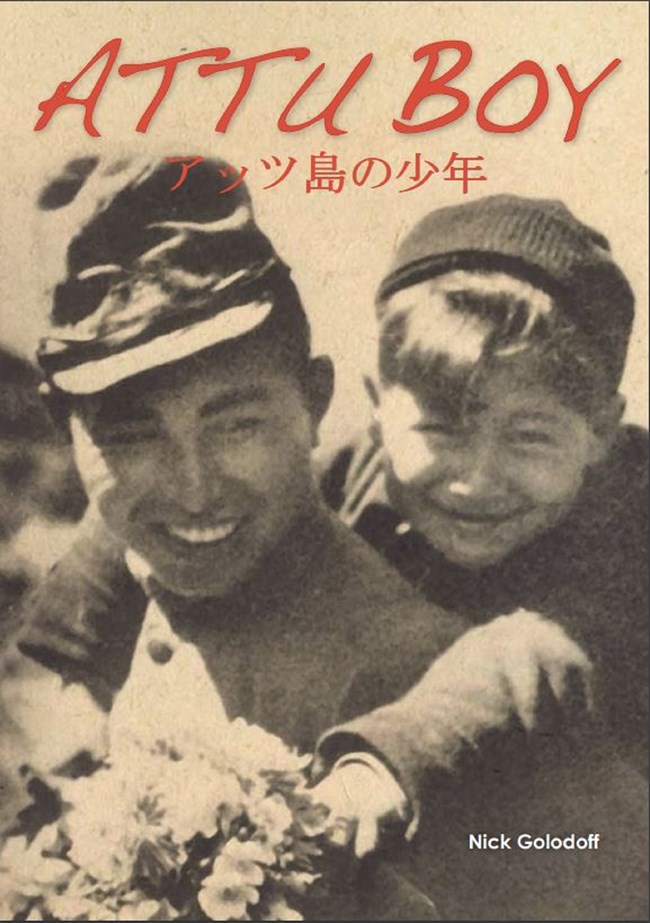

Food for Attuan Prisoners in Japan

Note: Nick Golodoff was six years old in June 1942 when the Japanese invaded his village, Attu, and took the residents prisoner. His memories of the invasion, imprisonment in Japan, and return to the Aleutians were compiled in the 2012 NPS publication, Attu Boy (pdf). The following information comes from Nick’s memoir.

Three months after the Japanese invaded Attu Island, the officers told the 41 residents of Attu village to board a boat, urging them to brings as much food as possible because it be hard to get food in Japan. Each family brought flour and sugar if they had it, along with barrels of salt fish.

Nick Golodoff’s mother Olean, interviewed in 1981, remembered the Attuans’ first meal in Japan when they arrived. During the boat trip, they had eaten their own food. Upon arrival in Japan, the villagers got a cooked meal served on trays with chopsticks. They ate with their hands when the policemen were not looking. Later, they used spoons they had brought from Attu.

They ate relatively well as long as they still had their fish from home. In their first house, the women cooked for all of them on a stove they had brought from Attu. After their own food was gone they only got a handful of rice a day. One of the Attuans’ daughters said that her mother never liked rice again after the war.

Later in the war, the Attuans had more freedom to look for food outside their dormitory. Nick remembered two fruit trees near the house. They weren’t allowed to pick the fruit, but Nick went out to pick up what had fallen. The policeman took the Attuans down to the beach and they found some small crabs. He also bought “kite fish,” undesirable to most Japanese, in a store and cooked it for the Attuans. Once he brought goat meat. The Attuans, even young Nick, could see that the Japanese were hungry too. They appreciated the kindness of the policeman and other Japanese who shared with them despite their own hunger.

As the war progressed, the Attuans suffered more from hunger and malnutrition. They scavenged peelings dropped on the ground. The boys went out at night and stole food, then shared it with others. As things got worse, the Attuans dug in the garbage for food. The chief, Mike Hodikoff and his son died from food poisoning after eating garbage. Once the men killed and ate two dogs, giving their portions of rice to the women. While the Attuans still had fish from home, traditional sharing prevailed and they cooked and ate communally. However, they eventually reached a point where sharing would mean starvation. Most of the Attuans who died in Japan were victims of starvation, malnutrition, and diseases exacerbated by hunger.

When they heard the war was over and they hoped to be rescued, the Attuans and the policeman who guarded them painted POW in big letters on the roof of their house. American planes flew over and dropped parachutes and drums with food, candy, gum, and cigarettes. Seventy years later, Nick still remembered the delicious canned peaches that were dropped. When they finally were relocated in Atka, according to Nick, “My family had no money so we had to live off the land, eating things like fish from the creek, roots, berries, sea urchins, mussels, clams, etc. But I still had better food than I ate when I was in Japan.” Atka was 500 miles away from home, but still within the Unangax̂ landscape; the Attuans returned to the familiar wild resources that had sustained them at home and in Japan.

FDR Presidential Library & Museum 48-22 3868(497)

Presidential Meal

by Karen Abel

What do you think one would serve when the President comes to town? Well, the President actually did visit the Aleutian Campaign in 1944 and it looks like he got a holiday feast! Luckily, so did the roughly 160 selected service men that joined him.

On August 3rd, 1944 the USS Baltimore tied up to Pier #7 in Sweeper Cove on Adak after a long 2335-mile journey from Pearl Harbor. On board was President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This visit was part of the President’s inspection trip through the Pacific and was the first and only time that he would visit this part of the country. He appeared impressed with what had been accomplished to date and made sure to mention it. After some official greetings aboard the ship, he disembarked to spend the rest of the morning touring the naval base and Admiral Whiting’s quarters before heading to the chief petty officers’ mess hall, a Quonset hut, where he had lunch with a varied group of enlisted men, covering all the service branches stationed there; Army, Navy, Marine and SeaBees.

According to the President’s Log,

“The bill of fare consisted of boiled ham, stewed tomatoes, mashed potatoes with cream gravy, string beans, chocolate pudding, bread, butter and coffee, and the meal was served to the President in a regular “GI” aluminum tray just as if it was for all others present.” Naturally.

In a post-lunch morale-boosting talk, he said. “Gentlemen, I like your food. I like your climate. (Laughter)” He then went on to praise the men on what had been accomplished so far in such a remote place.

“It's a treat to see this place and see what has been done here in such a short time. Say, for example, the spot where the Army moved a stream and made a harbor out of it. I have never been to this country before, but I know the parallel of it very well. I have spent lots of time up around the coasts of Maine and Newfoundland. And Americans of all kinds can live here and get by with it all right. I am thrilled with what we have done here. I wish more people back home could come out to Alaska and see what we have done here in an incredibly short time.”

FDR Presidential Library & Museum 66-93(5)

"A privilege to be with you"

And it is true, in just two years Adak had become a full functioning base that housed 22,000 personnel, 14,000 Army and 8,000 Navy covering a vast area of land. Do you know how many mess halls it takes to feed that many servicemen? A lot. He concluded with thanking them for their dedication to country.

“It has been a privilege to be with you, and to see this pioneer work. You are doing it awfully well—doing a good job, first, for the defense of your country, and secondly you are doing it for the future of our Nation. You are making our future secure for the years to come, more so than it has been in the past; and it took this war to make us do it.”

The entire lunchtime affair lasted for one and a half hours. Afterwards, the President continued his tour of the base, which included inspections at the Army area on the hill, the Naval Air Station and lastly the enormous warehouses along Sweeper Cove. In keeping with the Aleutian theme, the USS Baltimore’s scheduled departure time of 1605 came and went as the winds and surf howled against the dock. The visitors thus learned first-hand that the Aleutian weather bears no mercy, not even for the President. At least he was well fed!

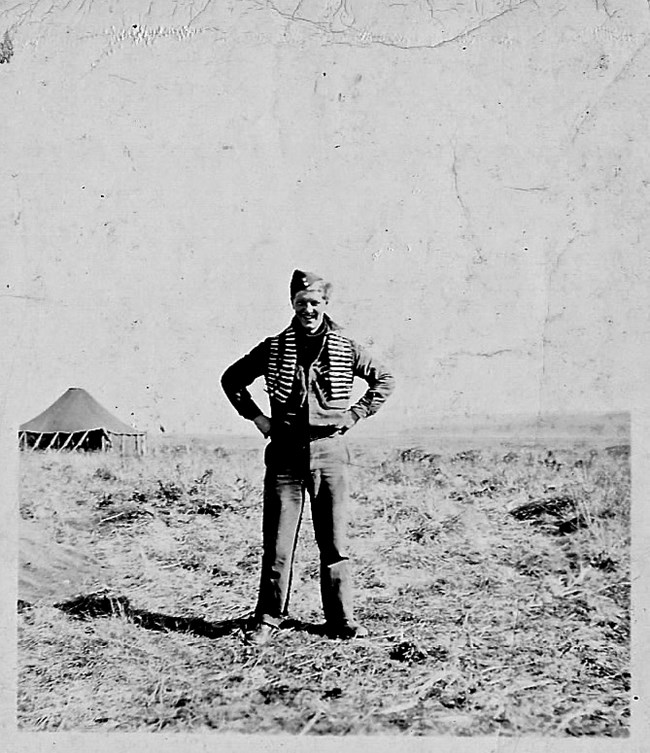

Courtesy of Harold Cross, via Karen Abel

Profile: Harold Cross

By Karen Abel

Harold Cross was the last living member of 111 (F) Squadron, one of the two Canadian fighter squadrons stationed in the Aleutians during the war. He was an air frame mechanic and serviced all parts of the squadron aircraft: Kittyhawks (P-40’s) and Harvards (T-6’s). Harold was born in 1922 in Vancouver, Canada, joining the RCAF in 1941. After basic training, he was posted to the newly formed 111(F) Squadron, RCAF who were just being established specially because of the threat of war coming to the home front. He, along with the rest of the aircraft maintenance crew, was sent to the Curtis Wright factory in Buffalo, New York where they were formally trained to maintain and service the P-40 Warhawks or Kittyhawks, as they were called in Canada.

It was just after they returned to their training base in Rockcliffe, near Ottawa, Ontario, the first week in December 1941, that the squadron was notified of their move west to Patricia Bay on Vancouver Island. They would become part of Canada’s Western Air Command dedicated to fortifying the Canadian west coast, or so they thought. Six months later, he found himself along with his squadron mates, on the move again, heading north to Alaska. On June 5th, 1942, Harold became part of an advanced party who had the fortune of boarding a Supermarine Stranraer flying boat headed for Anchorage, arriving in just a few days. The rest of the ground crew instead boarded the SS Denali whose journey lasted the better part of two weeks! The 111(F) pilots, 17 of them with their Kittyhawks, flew in echelon in two groups, leaving two weeks apart.

The squadron spent 2-4 weeks at Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage. Harold remembers fondly a local man who lived remotely and introduced them to hot buttered rum--the best he’d ever had!

Courtesy of RCAF veteran Staff Sgt. A.C. Killip Photo Collection, Alaska Military History Association

First Impressions of Chow

From Elmendorf, they headed west to Umnak where Harold's first impressions of chow time in the Aleutians are vivid:

“Talk about first impressions, I guess I still have that first impression. The mess tent was a series of tents with the sides turned up so it was just a roof. And the serving area was a series of 45 gallon drums turned into stoves with fire in the bottom. And that was it. You took your mess kit down and as I recall, the food was not that bad but everything they put in there turned into stew. Then when you got to the end of the line, you had your choice, in the second half of your mess kit, to get coffee or dessert. Or you could have the dessert in with the meal and have coffee. Or you could turn this piece of the kit over and protect your meal from the rain because by the time you got to the mess tent it was raining like hell. And then you went and found yourself a place to sit and eat your meal. Now, if you can picture that, everything is scrambled together in one mess tin and you had a choice of course, you could sit down somewhere and eat and get wet or your could go back to the tent; of course by the time you got back to the tent everything was cold. And that is the way it was all the time I was on Umnak, they never did build anything but that long line of 45 gallon drums sitting under a tent."

Harold’s first wartime Christmas was spent on Kodiak Island. The squadron just arrived, replacing the American 18th Fighter Squadron in protecting the main Naval Base. It is customary for the Christmas meal to be served by the Squadron Officers. Like the Thanksgiving meal, it might be a turkey and all the trimmings. Or it could be a luncheon consisting of cold meats, cold salads, beer and smokes! It is a good thing sweet potatoes are not a staple in Canadian holiday meals, because thanks to a mishap in either shipping or ordering sweet potatoes, holiday dinners would have been forever ruined for poor Harold.

“The food supply ship arrived once every three weeks. And one week the food ship arrived, and somebody told me that it was 30,000 cases of foodstuff that they unloaded, and in this particular case, it turned out to be 30,000 cans of sweet potatoes. And of course there wasn’t another supply ship for three weeks. To this day, I cannot eat sweet potatoes. The cooks, you had to give them credit, they did a fantastic job. You figure, on a day when it is blowing 90 knots and raining almost sideways and these guys are working in these so called ‘tents,' I have to say that the food, the whole time we were there, was good the way it was cooked. The way you got it wasn’t all that good but…(laughs). But when they ran out of the residual stuff that they had left over from previous supply drops, for about a week, sweet potatoes fried for breakfast, boiled for lunch and then a meatloaf form for dinner, it got to be a bit….That really soured me on sweet potatoes I must say."

Needless to say, he has not eaten a sweet potato since!

Courtesy of Karen Abel

After Alaska

Harold stayed with the squadron until February 1943, before being posted back to Canada to get his flight engineer designation at the insistence of his Alaskan-based Squadron Leader, Kenneth Boomer, DFC, AA. After the group returned from the Aleutians, the 111(F) squadron was sent to the European Theater and was re-designated the 440 (FB) Squadron Flying Typhoons. At the end the war, they would return to Canada and eventually relocate to Yellowknife, where they still operate as a Royal Canadian Air Force Transport Squadron.

After the war, Harold began working for the federal government in various roles and ultimately would act as the Territorial Secretary to the Commissioner of the Northwest Territories. He spent half a decade living in its capitol, Yellowknife. Little did Harold know that eventually his old wartime squadron would also be stationed in Yellowknife!

I think it is worth noting that most of the pilots Harold served with during World War II never made it home after the war. Twenty-three of its 31 pilots who went on to Europe after Alaska were killed in action.

Sadly, Harold passed away just in May 2020 at the young age of 98. He still lived alone and before the pandemic hit, he made a point of going out everyday in a suit to a local restaurant that was named after him, in honor of his loyal patronage--Harold's Bistro, located at the Sheraton Vancouver Airport. If you are in the area, check it out, and tell them Harold sent you.

References:

Dunham, Mike. 2010. “Forgotten Battlefield Museum Offers Rare Look at Kiska War. Anchorage Dispatch News, 5/30/2010.

Golodoff, Nick. 2012. Attu Boy (pdf).

Makarin, Irene. 2004. Interviewed by Ray Hudson for the NPS Lost Villages Project.

National Park Service. Charles House Letter, accessed 12/8/2020.

Obmascik, Mark. 2019. The Storm on Our Shores. New York: Atria Books.

To receive an email notification of, and link to, the newest issue of Williwaw when it is released, please email us to subscribe. If you would like a paper copy mailed to you, please let us know in your email.

You may unsubscribe at any time. We will not email you except when new issues of Williwaw are released (generally quarterly). We will not share your email address with anyone else.

Last updated: December 19, 2020