Last updated: June 21, 2020

Article

Western Museum Laboratories

The Western Museum shops in Berkeley, California employed artists and craftsmen under many New Deal programs to design and create museum exhibits. The laboratories were operated as a joint project between the National Park Service and the University of California.

NPS Photo

Work was done in three different buildings on and near the Berkeley campus: Hilgard Hall on the campus, the ECW Laboratory on College Avenue, and the rented Federal Land Bank Building just off campus. Located on Fulton Street next to Edwards Field in Berkeley, it was sometimes referred to as the Fulton Laboratory. Carpentry work and casting were done at the ECW Laboratory where the labor force consisted of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) workers. Public Works Administration (PWA, and Works Progress Administration (WPA) workers also provided labor for the exhibit projects.

NPS Photo

Tumacácori's Museum Exhibits

All of Tumacácori National Monument’s original museum exhibits were made at the Western Museum Laboratories.

From Museum Curatorship in the National Park Service 1904-1982, by Ralph H. Lewis, 1993:

“In the 1937 fiscal year Public Works allotted $50,000 to the Park Service for an administration/museum building at Tumacácori National Monument. After a brief altercation between Burns and Hall, [directors of the eastern and western branches of NPS museum laboratories] the exhibit planning and preparation responsibility came to rest at Berkeley. PWA curator Russell Hastings and Captain D.W. Page prepared the exhibit plan, approved by the director in January but considerably modified as research and preparation continued."

Exhibits and cases for the new museum were built at the labs in 1936 and 1937. In January 1938, two and a half tons of museum cases arrived by train in Nogales and were driven to Tumacácori in two trucks. Exhibits arrived on May 28 and were installed by Berkeley museum technicians Bert Floyd and Lorenzo Moffett.

Custodian Louis Caywood commented:

“Moffett and Floyd remained here until June 8 on installation. Hours seemingly meant nothing to them, as they were often working from 7:00 a.m. until 7:00 p.m., including Sundays.”

Bronze Statue of Father Kino

Eugene Morahan (1869-1949) in 1936 sculpted the bronze equestrian Kino statue that stands in the museum breezeway. Born in Brooklyn, Morahan studied with Augustus Saint-Gaudens and lived in Santa Monica, California from 1930 until his death. Included in his many works are the Soldiers and Sailors World War I monument in Brooklyn dedicated in 1921, bronze bas-reliefs on two faces of an 18-foot tall pink granite stele. He also sculpted the 18-foot statue of St. Monica in Santa Monica in 1934, a project funded by the PWA.

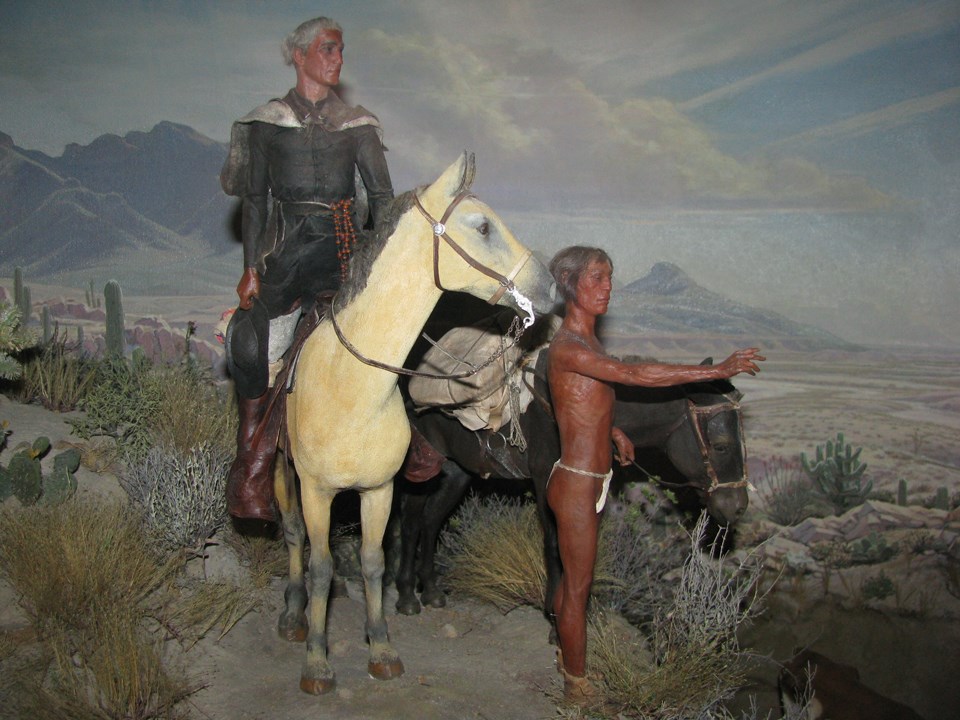

Kino Diorama

The dioramas contain incredibly detailed figures. The figures were constructed on a metal skeleton framework. Bodies and features were then sculpted in wax and painted, and the figures were given fabric clothing.

Arthur Woodward, NPS historian and archeologist and member of the 1935 PWA architectural expedition, visited the park in 1977 to attend the fortieth birthday celebration for the museum. He stood and examined the Kino diorama for quite a while. Finally he turned and said, "I researched the clothing he's wearing and it's authentic, right down to the underwear.

Tubutama Diorama

Originally, the figures in the diorama showing the attack on Tubutama during the Pima Revolt of 1751 were crowned with real hair, which was black except for two of them. In real life Father Sedelmayr was a red-headed Austrian and so he was given red hair, as was the young Pima boy he’s shielding. When the deteriorating hair was replaced in 1972, everyone was given black, museum artists’ humor and bureaucratic supervision apparently having changed during the interim.

Mass Diorama

Bartlett Frost used himself as the model for the most prominent figure in the mass diorama, the soldier kneeling in the foreground.

The appearance of lighted candles was achieved by small light bulbs beneath the altars. Balanced on a pinpoint just above the bulbs were flat, circular metal pieces cut like the vanes on a windmill so that the heat from the bulb caused them to turn. This made the candles flicker realistically but over time they gradually wore out and were not replaced.

The Rev. Celestine Chinn, O.F.M., served for many years at San Xavier del Bac, arriving there in 1949. He was a noted expert on religious iconography and on one of his visits to Tumacácori in the late 1970s was asked his opinion of the religious art portrayed in the mass diorama. “It’s all accurate,” he said, “except for that painting in the baptistery. It wasn’t done until 1875.”

One other error is the portrayal of the floor as being made of brick. Historically, it had a smooth, red plaster surface.