Part of a series of articles titled The New Deal at Tumacácori.

Article

Visitor Center Architecture and Historical Pastiche

A New Kind of Visitor Center

Rather than restore and reconstruct the mission complex on conjectural information, as had done at Mission San Jose in San Antonio and other locations, the National Park Service historians, archeologists, and architects decided to preserve what remained of the adobe mission structures and instead put considerable effort into interpretation. This effort included the development of museum exhibits, but more importantly the construction of a museum that was an exhibit in itself.

Frank "Boss" Pinkley, the National Park Service head of the Southwestern Monuments, had definite ideas for the museum. He wanted a low building that would not interfere with the historic mission complex and that was close to the parking lot so that visitors entered immediately. He wanted a pleasing facade, but nothing too ornate. He felt the building should be large enough for future expansion if required, but of a design that complemented the mission's architecture. He wanted reproductions of doors, windows, and floor and ceiling structure that were found in other Sonoran missions of the Kino chain. He also wanted a "view room" where visitors could look out at the mission complex, and he even set the axis of the museum building at a particular angle so that visitors could see that "knock-out" view he chose.

The 1935 Expedition

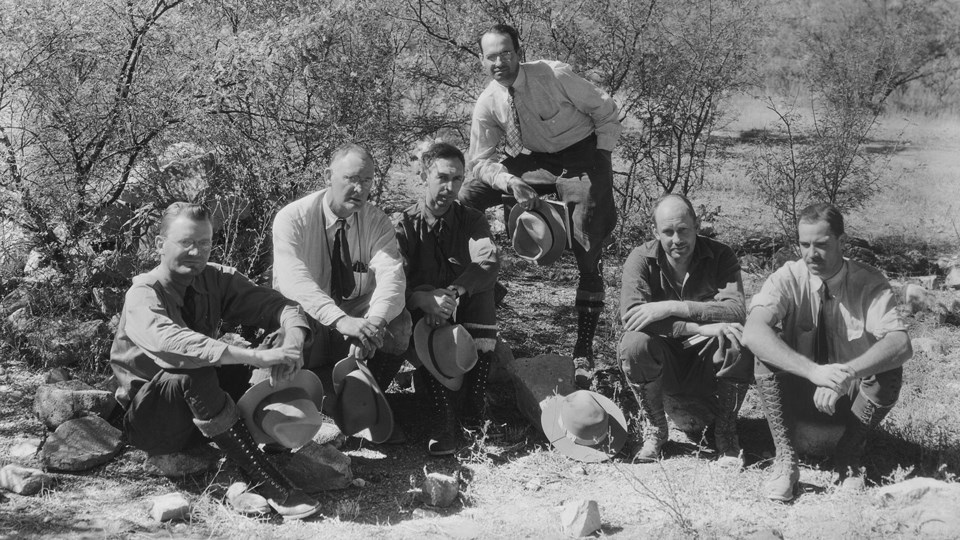

The design for Tumacácori’s visitor center evolved from a 1935 expedition to thirteen Spanish colonial mission sites in Sonora and two in Arizona, at a time of political and social unrest in Mexico. During this period of anticlerical activity all the churches had been closed and their furnishings removed, hidden by local parishioners or destroyed. The trip was funded and authorized by the National Emergency Council, a branch of the PWA which coordinated work among federal agencies.

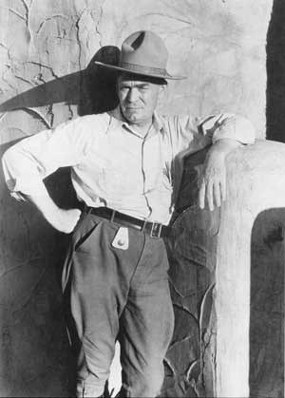

George A. Grant, 1935

Six intrepid NPS professionals made the trip: Arthur Woodward, archaeologist and journalist; Scofield DeLong and Leffler B. Miller, architects; George A. Grant, photographer; Robert H. Rose, naturalist; and J.H. Tovrea, engineer. The report was republished by Buford Pickens in 1993 as The Missions of Northern Sonora, a 1935 Field Documentation (University of Arizona Press).

Various architectural features of the churches are visible in the construction of the visitor center building.

Front Entrance

Left image

Cocóspera

Credit: (photo by George Grant, 1935)

Right image

Tumacácori visitor center entrance

Front Doors

Left image

San Ignacio

Right image

Tumacácori visitor center door

Spindles

Left image

San Pedro, choir loft railing

Credit: (photo by George Grant, 1935)

Right image

Tumacácori visitor center window grille

Ceiling

Left image

Oquitoa, roof (photo by George Grant, 1935)

Right image

Tumacácori visitor center ceiling

Panelled Doors

Left image

San Igancio, doors

Credit: (photo by George Grant, 1935)

Right image

Tumacácori museum doors

Arcade

Left image

Caborca

Credit: (photo by George Grant, 1935)

Right image

Tumacácori visitor center (view from inside mission grounds)

Niche

Left image

San Ignacio, niche

Credit: (photo by George Grant, 1935)

Right image

Original visitor center drinking fountain

Groined Vault

Left image

San Xavier baptistry

Credit: (photo by Donald W. Dickensheets, 1940)

Right image

Tumacácori's model room ceiling

Corbels

Left image

Pitiquito, corbel

Credit: (photo by George Grant, 1935)

Right image

Tumacácori model room corbel

Finials

Left image

San Xavier finials

Credit: (photo by George Grant, 1935)

Right image

Tumacácori finial above model room

National Center for Preservation Technology and Training

Watch "History By Design: The Tumacácori Visitor Center as Historical Pastiche"

Louis Caywood states in his June 1937 year-end report:

“The Secretary of the Interior approved an allotment of Public Works funds for the new Tumacácori museum in August, 1936; the contract for construction was let to the M. M. Sundt Construction Company (of Tucson) in June. It is expected that the building will be finished early in 1938. Western Museum Laboratories of the National Park Service in Berkeley, California, had prepared 60 percent of museum exhibits at the end of the fiscal year. Plans had been drawn up by the Museum Division with some help by the Southwestern Monuments office. Exhibits will be ready for installation when the building is finished, it is hoped.”

Construction by the M. M. Sundt Company began in August, 1937 despite a heavy rainstorm that ruined the first batch of adobe bricks. At the same time a contract was let with Citizens Utility Company of Nogales and electricity finally reached the park. Work on the visitor center building was completed in December, 1937 at a total cost of $28,992.91.

While construction of the visitor center and museum was going on, the exhibits for the museum were being designed and built in Berkeley, California at the Western Museum Laboratories by artists, craftsmen and designers employed under many New Deal programs. Lorenzo Moffett and Paul Rockwood, PWA exhibit builders from the Berkeley labs, spent four days at the monument in February 1937 making paintings, drawings, photographs, and color notes for details in the dioramas being prepared in California.

Exhibit installation followed in 1938. With all installation complete, the museum was dedicated in April 1939.

Last updated: March 10, 2021