Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

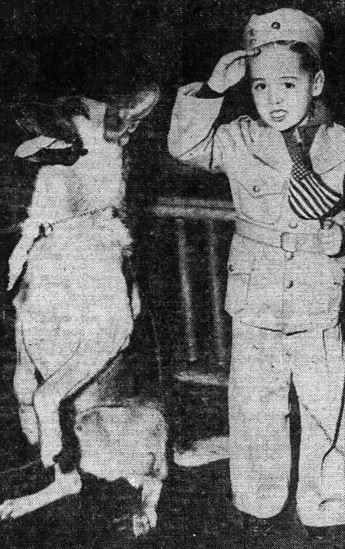

Star Press (Muncie, Indiana), January 14, 1943, p. 4.

Before the US entered World War II, the US Army had only a few sled dogs that they used in arctic regions. The military was not convinced that dogs would be useful in war. After the Japanese attacked the US home front, civilians including those from the dog show world established the Dogs for Defense program.[1] In July 1942, the responsibility for training the dogs was transferred to the Quartermaster Corps, and by the fall, dogs were being trained for the Navy, Marines, and Coast Guard. Dogs for Defense remained active in procuring dogs until March 1945, when the Quartermaster Corps took over. [2]

Enlisting America's Dogs

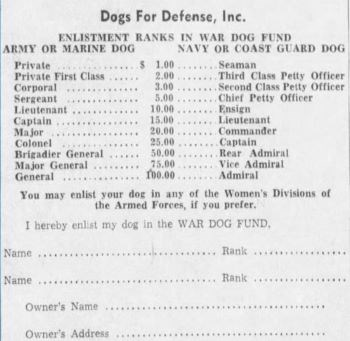

Owners volunteered over 40,000 pet dogs for wartime service, spurred in part by the 1942 War Dogs movie (which is available to watch online). In some cases, those enlisting in the military also enlisted their dogs.[3] At first, only certain purebred dogs were recruited. After training trials and a shortage of purebred dogs, the criteria were changed to include some 30 breeds and cross-breeds including German Shepherds, Dobermans, Boxers, Labrador Retrievers, and St. Bernards. The criteria were shortened again in 1944 to just seven breeds.[4] Dogs that did not meet military requirements (or whose family did not want to volunteer them) could be enrolled in the doggy Home Guard. For a $1 fee, dogs got the rank of private or seaman (depending on branch of service selected); for $100, they got the rank of general or admiral. The money supported the Dogs for Defense program, and even President Roosevelt’s dog, Fala, enrolled.[5]

Knoxville News-Sentinel (Knoxville, Tennessee), April 21, 1944, p. 17.

A Different Kind of Obedience Training

After meeting basic requirements and passing a preliminary physical, 18,000 of the volunteered pet dogs were sent to one of several Army training centers.[6] These were located at Fort Robinson, Nebraska; Front Royal, Virginia; Camp Rimini, Montana; Cat Island, Gulfport, Mississippi; and San Carlos, California. Temporary training centers were also setup at Fort Washington, Maryland and Fort Belvoir, Virginia for training dogs for mine detection. An installation at the Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville, Maryland researched nutrition and worked on an Army dog ration.[7] The first formal military training manual for dogs in warfare was written by Alene Stern Erlanger, a dog breeder and organizer of Dogs for Defense. It was published by the US War Department as TM 10-396 Technical Manual: War Dogs, on July 1, 1943.[8]

Dogs on Duty

After training, war dogs and their handlers (who also received training) were ordered to their posts. A total of 10,368 war dogs went into active service: 7,665 to the Army and 3,174 to the Coast Guard.[9] War dogs fulfilled many duties, including as sentries/guard dogs, silent scouts on reconnaissance patrols to identify threats; messengers to carry important information, emergency supplies, or pulling communication wires between outposts; and finding wounded soldiers on the battlefield.[10] A total of fifteen Quartermaster war dog platoons were organized. Each platoon included 18 scout dogs, 16 messenger dogs, 20 enlisted men, and 1 officer. The hearing and smelling abilities of the war dogs made them especially useful in the thick jungles of the Pacific.[11]

Bonnie Wiley, “Canine Warriors Hound the Nips.” Hartford Courant (Hartford, Connecticut), May 7, 1944, p. 69. (The derogatory term for the Japanese was in common use during the war; it is no longer an appropriate term.)

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 6493413).

Returning Home

After the war, despite the time and cost involved, the military re-trained surviving dogs for civilian life. Dogs were returned to their owners if possible. The rest were adopted out, with priority given to servicemen and families whose pets had been killed in action. At the end of the war, 559 war dogs serving with the Marines survived. Five hundred and forty of them were adopted out (or remained with their handlers); the remaining 19 were euthanized – 15 for health problems, and only 4 because they couldn’t be retrained.[12] The first official war dog monument in the United States is the National War Dog Cemetery on Guam. It honors the 25 war dogs killed when the US Marines retook Guam from Japanese forces in 1944.[13]

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] Golden 2017; Kiser 2020; Paltzer n.d.

[2] Miller 1961: 616; Paltzer n.d.; Smithsonian Institution n.d.

[3] Commercial Appeal 1943; Journal Times 1943; Miller 1961: 616; Times Herald 1943. War Dogs was directed by S. Roy Luby. There was also a 7-minute animated short called War Dogs released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer in 1943.

[4] Miller 1961: 618.

[5] Golden 2017.

[6] Golden 2017; Kiser 2020; Miller 1961: 616; Paltzer n.d.

[7] Erlanger 1944; Miller 1961: 617; Paltzer n.d.; Smithsonian Institution n.d. Cat Island is part of the NPS unit, Gulf Islands National Seashore. Fort Robinson and Red Cloud Agency was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark District on December 19, 1960. Fort Washington was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. The Belvoir Mansion Ruins and the Fairfax Grave, located on the grounds of Fort Belvoir, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 4, 1973. At the facility on Cat Island, the Army tried to see if the dogs could identify the enemy by smell. Despite their unjust incarceration in War Relocation Centers, several Japanese Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans) joined the military. Some of them were sent to Cat Island to test the Army’s theory.

[8] Golden 2017; Paltzer n.d.

[9] Miller 1961: 619.

[10] Erlanger 1944; Paltzer n.d.

[11] Paltzer n.d.

[12] Golden 2017; Kiser 2020.

[13] United States Department of Defense 1996.

Commercial Appeal (1943) “They’re All In The Army.” Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee) January 1, 1943.

Erlanger, Alene (1944) “The Truth About War Dogs.” The Quartermaster Review, March-April 1944. Reproduced at The Army Quartermaster Foundation.

Golden, Kathleen (2017) “Dogs for Defense: How Skip, Spot, and Rover Went Off to Fight World War II.” O Say Can You See: Stories from the Museum, National Museum of American History, August 17, 2017.

Journal Times (1943) “Husband, Wife and Dog Now in US Service.” Journal Times (Racine, Wisconsin) March 5, 1943, p. 19.

Kiser, Toni M. (2020) “Dog Day Afternoon.” National World War II Museum, August 26, 2020.

Miller, Everett B. (1961) United States Army Veterinary Service in World War II. Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army, Washington, DC. Collection of the National Library of Medicine.

Paltzer, Seth (n.d.) “The Dogs of War: The U.S. Army’s Use of Canines in WWII.” Army Historical Foundation.

Smithsonian Institution (n.d.) “World War II Patriotic Cover.” Smithsonian Institution.

Times Herald (1943) “Chinese and His Dog Enlist.” Times Herald (Port Huron, Michigan), January 2, 1943, p. 8.

United States Department of Defense (1996) “View of the Marine Corps war dog cemetery built in memory of the twenty-five combat trained dogs that lost their lives in the bitter fighting for the liberation of Guam.” Photo by Dawn C. Montgomery, American Forces Information Service, Defense Visual Information Center. Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front During World War IIMaterial Drives

The Home Front During World War IIMaterial DrivesCelebrities including Mickey Mouse and Bing Crosby urged Americans to “Salvage for Victory” and “Get In The Scrap.”

-

The Home Front During World War IICurrency on the World War II Home Front

The Home Front During World War IICurrency on the World War II Home FrontPaper money and coins saw changes because of the war. New materials and new types of money reminded people every day that the US was at war.

-

The Home Front During World War IIRationing of Non-Food Items

The Home Front During World War IIRationing of Non-Food ItemsRationed items included tires, cars, bicycles, gasoline, home heating fuels, shoes, stoves, footwear, and typewriters.

Tags

- national register of historic places

- national historic landmarks

- women’s history

- engaging with the environment

- world war 2

- wwii

- ww2

- world war ii

- home front

- homefront

- military history

- dogs

- american world war ii heritage city program

- american world war ii heritage city

- awwiihc

- indiana

- ohio

- wisconsin

- north carolina

- pennsylvania

- illinois

- michigan

- washington dc

- nebraska

- virginia

- montana

- mississippi

- california

- maryland

- guam

- wyoming

- connecticut

- kansas

- gulf islands national seashore

- fdr

- fort robinson

- front royal entrance

- camp rimini

- gulfport

- san carlos

- fort washington

- fort belvoir

- beltsville

- chicago

- wichita

- hartford

- east hartford

- binghamton

- new york