Last updated: May 16, 2024

Article

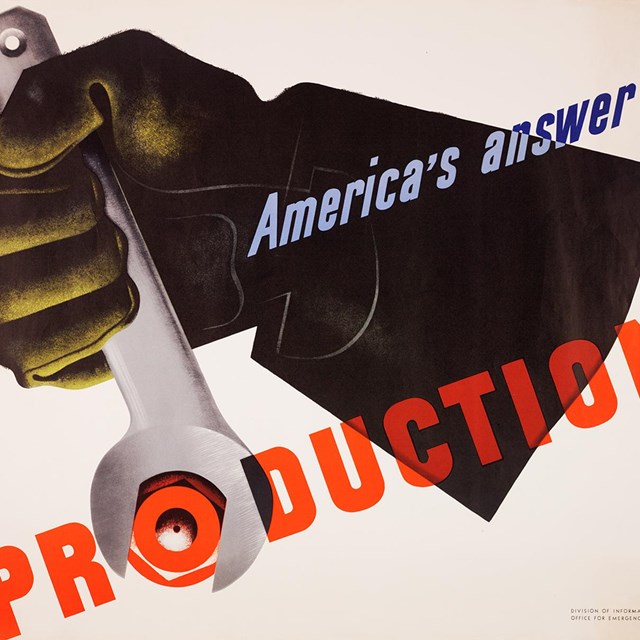

Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

Left image

“Throw YOUR Scrap Into The Fight! American Industries Salvage Committee.” Poster, Office of War Information, ca. 1944.

Credit: Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 515814).

Right image

“Scrap.” Poster, War Boards, United States Department of Agriculture, 1942.

Credit: Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 515359).

“Shortages in domestically produced raw materials were not expected, for the mobilization plans were not based upon a war of such magnitude that it would exhaust current production of steel, copper, aluminum, brass, and other material resources of the United States. Early in 1942, however, it became clear that the mighty military effort then being developed would cause grave shortages in the above-named metals and in many other raw materials.”[1]

Rationing was one way that the government offset shortages in needed war materials. Another was a program encouraging companies and citizens to collect and contribute them. As a way of making the program relevant and that individuals could make an important contribution, promotions spelled out how much of each material went into a wartime product.[2] Celebrities including Mickey Mouse and Bing Crosby urged Americans to “Salvage for Victory” and “Get In The Scrap.”[3] These programs provided needed materials for the war effort, but also gave civilians meaningful ways to contribute. The main items collected were metal, rubber, paper, and kitchen fats. Other items, including milkweed floss and women’s stockings, were also collected for the war effort.

Because people donated items made of these materials, there are fewer of them left to represent the years leading up to the war. Material drives for aluminum, copper, and shellac, for example, claimed evidence of American pre-war music and radio history. Shellac is a resin that comes from the lac bug. From the late 1800s through the mid-1900s, it was used to make record albums.[4] As part of the war effort, records were collected and the shellac re-used to press new albums for distribution to the troops overseas. Hundreds of millions of records were donated. The aluminum and copper masters used to press albums were also donated, as were aluminum disks holding recordings of early radio broadcasts. With these masters gone, we don’t really know what pre-war culture we have lost. The Library of Congress maintains a list of recordings compiled from surviving catalogs that it is looking for. But it isn’t a complete list of what has been lost. It is only through chance finds of surviving recordings that let us hear these pieces of history.[5]

Left image

“Save Your Cans: Help pass the Ammunition.” Poster, Salvage Division, War Production Board, c. 1944.

Credit: Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 515347).

Right image

“Get In The Scrap.” Poster, Bureau of Industrial Conservation, War Production Board, 1942.

Credit: Collection of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (MO 2005.13.35.280).

Collection of the David L. Rice Library, University of Southern Indiana (MSS 264-0998).

Metal

The war effort needed tons of metals—for tanks, ammunition, planes, warships, and for packaging rations. These included tin, copper, aluminum, steel, and iron. Rationing and the transition of civilian factories to wartime production limited what metal goods were available.[6] Things like refrigerators, cars, and even cutlery were just not available during the war. Other items, like processed foods, were rationed—not only because the food was scarce, but also because the cans themselves were.[7]

Scrap steel is a key component in turning iron ore into steel.[8] Before Pearl Harbor, the US had sold tons of it to Japan. To offset the resulting shortage, the government collected scrap from industry, agriculture, and civilian homes. In 1942, a peak of 24 million tons of metal was salvaged. Only slightly less was salvaged in each of the rest of the war years.[9]

Collection of the Library of Congress

Families donated pots and pans, metal toys, broken tools and equipment. Some (including actress Rita Hayworth) removed metal fenders from their cars. Towns and cities (including Dayton, Ohio) sent historic cannons and monuments for salvage. Others salvaged metal fountains and wrought iron fences from cemeteries. In Rapides Parish, Louisiana the local sawmill added their scrap metal to the local school’s metal drive.[10] Storekeepers collected empty tin toothpaste and shaving cream tubes from customers before selling them a new one.[11]

Across the country youth groups including the Girl Scouts of the USA organized regularly occurring can drives. They would collect the clean, crushed cans put out by householders and sell them for scrap as a fundraiser.[12] Even though processed foods were on the ration list, 90% of consumers still bought them. This meant that throughout the war, there was a regular supply of cans for salvage.[13]

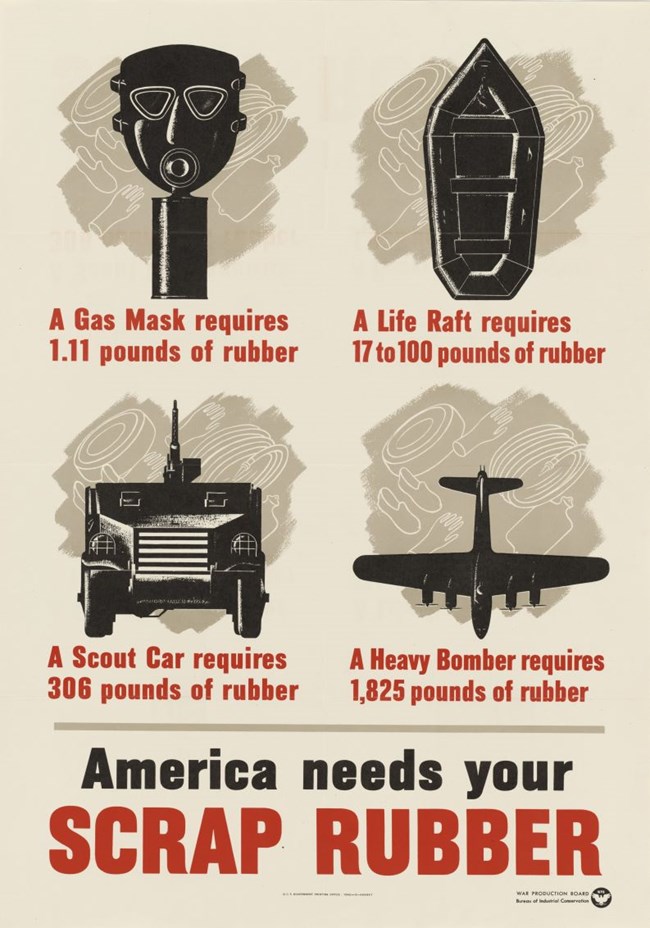

Rubber

Rubber was critical to the war effort. The military needed it for gas masks, boots, tires, seals, pontoon bridges, and life rafts -- among other things. When Japan conquered Malaya and the Dutch East Indies early in 1942, they cut the US off from its primary source of natural rubber.[14] Rubber was so important that the head of the Army and Navy Munitions Board said that unless they had a good replacement, the US would have no option but to "call the entire thing [World War II] off."[15]

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 513799).

US companies knew how to make synthetic rubber, but there wasn't enough manufacturing capacity. And so, the government put conservation efforts in place. Most civilian rubber use was as car tires. As well as requiring people to sell back any tires in excess of five (the four on their car plus a spare), the government implemented gasoline rations and lowered the speed limit. These reduced wear on those tires still in use, lengthening the time until they needed to be retread or replaced.[16]

For the last two weeks of June 1942, the government held a nation-wide rubber drive. Civilians brought their used and surplus rubber items to collection stations (often located at gas stations or garages), where they received a penny a pound.[17] People brought in hot water bottles, rubber bands, rubber boots, garden hoses, and their rubber duckies.[18] Through this effort, the government collected about 450,000 tons of scrap rubber. And though it could not be used for military products, it was used to re-tread car tires and for other civilian uses. This, in turn, freed up other, better quality rubber for the war effort.[19]

As noted above, there were the beginnings of an American synthetic rubber industry at the start of World War II. But synthetic rubber was expensive compared to natural rubber. And so, even though B.F. Goodrich marketed synthetic rubber tires in 1940, there was not enough industrial capacity to supply the US and its military.[20]

To fix the supply problem, the government paid to build and open 51 synthetic rubber factories. And they contracted with the four big rubber companies (Jersey Standard, Firestone, B.F. Goodrich, and Goodyear) for 400,000 tons of synthetic rubber per year.[21] The result was that by 1944, there was enough synthetic rubber being produced to meet the demand.[22] Reclaimed rubber was no longer required for the war effort.

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/2017693664).

Just as typewriters were needed for all the paperwork involved in the war effort, so was paper. Paper for draft cards, record keeping, letters home, orders, and discharge papers. And for packing field rations, making ammunition and parachute flares, paper training targets, and for paper wallboard and insulation for barracks. Altogether, several hundred thousand military products used paper.[23]

Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph (Pittsburgh, PA), January 14, 1945, p. 13.

Despite government limits on paper use by publishers in the US, there still wasn't enough paper for the war.[24] As well as the booming demand by the military, civilian product packaging was also using more paper to replace cans. And there was a shortage of wood pulp needed to make paper. Men who had worked as lumberjacks were moving into better-paying war production jobs. And there was less pulp wood available for import, since countries like Canada, who exported a lot of their product to the US, needed their own increased wartime supply.[25]

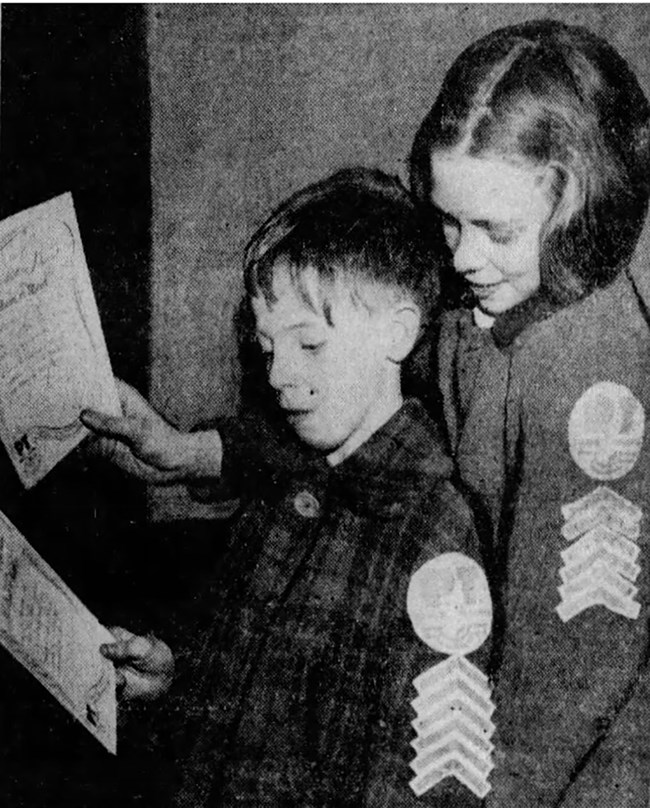

Promotions urged homemakers to save their waste paper and donate or sell it to a collector. In Manitowoc, Wisconsin, the town held a “waste paper ball” with music and dancing. The cost of a ticket was a bundle of scrap paper.[26] Across the country, youth groups and schools organized regular paper drives, arranging pickup from local residents.[27] These “Paper Troopers” could earn chevrons and ranks based on their successes.[28] In Manitowoc, the Boy Scouts collected almost 2 million pounds of scrap paper between 1942 and August of 1946.[29]

Not everyone involved was a patriot. In 1944, a junk dealer in Raleigh, North Carolina collected scrap paper intended for a Jaycees (Junior Chamber of Commerce) paper drive. The Jaycees had made arrangements with another dealer to collect the 25 tons of paper and pay them $14 per ton, which they then would use for charitable purposes. Court proceedings showed the value of the stolen paper as $350 (about $6,000 in 2023). The crooked junk dealer was ultimately charged with 3-5 years in prison. He fought his sentence all the way to the US Supreme Court (but lost).[30]

Left image

“Don’t Burn Waste Paper: Our war effort needs it: Call A Collector!” Poster, Division of Information, Office for Emergency Management, ca. 1944.

Credit: Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 514136).

Right image

“Save Waste Paper: Give Or Sell It! Call Your Salvage Committee Today!” Poster, Office of War Information, 1944.

Credit: Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 515345).

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 515344).

Kitchen Fats

The fat salvage program began in 1942 in Chicago, organized by a group of soap manufacturers. Its success (and complaints that lard – an edible fat – was being released by the government for soap manufacture) prompted a nation-wide collaboration between government and private industry.[31] Soap making uses purified fats like those contributed to the war effort. A byproduct of the process is glycerine, used to make the explosive nitroglycerine.[32]

Homemakers (especially in the South) were already saving fats – almost 75% saved bacon and other grease to cook with.[33] The challenge was to divert the fats for wartime use. The public campaign emphasized the war impact of salvaging them. One ad proclaimed that only 1 tablespoon of waste fats per day would load 1,542 machine gun bullets per year. Another described one pound of fat enough to “fire four 37-mm anti-aircraft shells & bring down a Nazi plane” and “enough dynamite to blow up a bridge and stop an invader.”[34]

Kitchen fats included those left over from cooking: bacon grease, pan juices, rendered down meat trimmings, fats skimmed from stews, gravies, and boiled sausage, etc. Once strained into a container, fats needed to be kept cool place so they wouldn’t turn rancid. Pressured by soap manufacturers, the War Production Board and the Office of Price Administration agreed to pay consumers for their fats. For each pound of kitchen fats turned in at their butcher, consumers received 4 cents and 2 red ration points. These red points, used for rationed meats, were in addition to those issued by the ration boards to each person.[35] As their part of the agreement, the soap and glycerine industries formed the American Fat Salvage Committee, and contributed money to advertise the program.[36]

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/2017696588).

From August 1942 through September 1946, the war effort collected more than 711 million pounds of kitchen fats. Almost 75% (528,759,000 pounds) came from civilian kitchens. Girl Scouts in Billings, Montana collected more than 23 of those tons in just 2 months. Military kitchens were the source of the rest.[37]

Altogether, salvaged fats met about 12 percent of total needed for soap production during the war. While there was a shortage of wartime soap, studies showed it was due to increased demand rather than limited production. Some thought that soap rationing would have been in the public interest; the soap dealers clearly felt differently.[38]

Milkweed and Stockings

Milkweed Floss

When Japan occupied what is now Indonesia during World War II, they cut the US off from the kapok tree. Fibers from the kapok were what made life preservers float.[39] With military action in both oceans and beyond, the military needed life vests. Based on scientific studies, the government landed on milkweed floss as a suitable alternative. Just a single pound of milkweed floss could keep a 150-pound person afloat for more than 40 hours. The challenge? Before the war, milkweed was a weed that people worked to get rid of. To grow a crop of it mature enough for military use would take 3 years.[40]

Photo by PookieFugglestein (Wikimedia).

The government needed 1.5 million pounds of floss in 1944. Each pound of floss needed an average of 825 milkweed pods.[41] To secure the needed milkweed, the government reached out youth groups like 4-H. Armed with 50-pound mesh onion bags, armies of children picked milkweed along the sides of roads, in meadows, and other wild places. Two bags, each of which held 600 to 800 pods, produced enough floss to make a life vest. The government paid from 15 to 20 cents per bag.[42]

After picking, the bags of pods were shipped to Petoskey, Michigan where the Milkweed Floss Corporation of America would process them to extract dried floss. The floss was then shipped to life vest manufacturers.[43] By the end of the war, over 2.5 million pounds of milkweed had been gathered, largely by children.[44]

Left image

“Oliver Lee (left) and C.J. Murphy help load milkweed pods collected in the county into a freight car for shipment.” Indianapolis Star 1944.

Credit: Indianapolis Star, November 22, 1944, p. 24.

Right image

“4 dozen pairs of all-silk stockings contain enough silk to make ONE POWDER BAG for a sixteen-inch gun.” Layout for a print ad, Office of War Information, Graphics Division, c. 1942.

Credit: Collections of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 7387564).

Women's Stockings

Women’s stockings – both nylon and silk – were collected for the war effort. Silk had been imported to the US largely from Japan. When Japan restricted and then eliminated all sales to the US before Pearl Harbor, the US was left with a shortage.[45] After developing ways to recycle silk and nylon stockings, the War Production Board began accepting donations. Between November 1942 and March 1943, 880,000 pounds of stockings (about one pair for every 2.7 women in the country) were collected. Among those collecting were the Girl Scouts of America (now the Girl Scouts of the USA).[46]

Silk was used for the gunpowder bags for large caliber guns. It was completely burned away when the gun was fired. All other available materials left a residue that needed to be cleaned between shots. Nylon from nylon stockings was re-spun into products like parachutes, ropes, and other materials.[47] While parachutes had been made from silk, just as the war was beginning, the US was developing a way to make them using nylon. This process turned out to make a superior product, and so recycling nylon stockings went into effect. A parachute contained nylon equivalent to 2,300 nylon stockings.[48]

Collections of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/98515057).

The Military Asks for Loaners

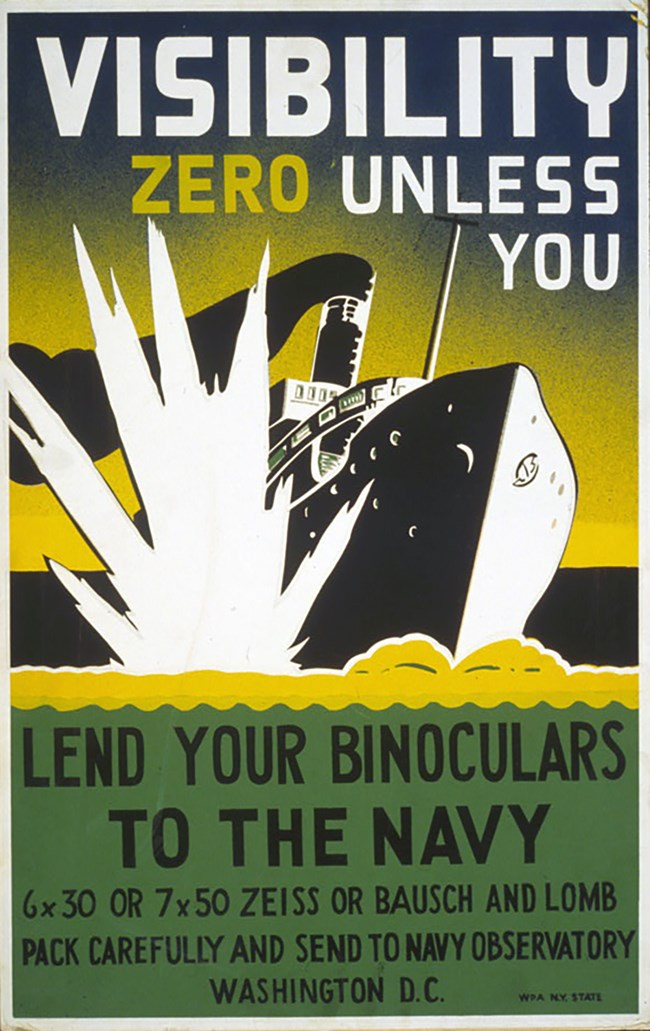

Most of the military asks were for donations to be used for the war effort. But in rare cases, they also asked the public for loans. One ask was binoculars. One was for the family dog.

Hey, friend… can you spare a pair? Before Pearl Harbor, only a few thousand pairs of binoculars were made in the United States every year. But once America was in the war, the military needed hundreds of thousands of pairs. To fill the gap while factories like Westinghouse in Mansfield, Ohio retooled to make them, the US Navy used a technique that was successful in World War I.[49] In 1942, they asked Americans to lend them binoculars.

To be suitable, the binoculars had to be either 6x30 (to see ships and large objects during ordinary navigation) or 7x50 (to see aircraft and ships at extremely far distances). And, because of the difficulty in getting spare parts, they would accept loan of only Zeiss or Bausch and Lomb binoculars. Americans were asked to tag their binoculars with their name and address, and send them to the Naval Observatory in Washington, DC. The Navy then paid $1 for each pair they kept for use, with the promise to return them if they were still in use after the war.[50]

In Mansfield, Ohio a Westinghouse factory transitioned from an idled refrigerator plant to shipping 100,000 pairs of binoculars to the US Navy within a few months (after the initial order, they supplied the US Army). A new air filtration system was installed, women were told they couldn’t wear makeup to work (which many saw as a relief), and mass-production processes were put in place. Women working in the plant brought their knowledge to the production floor. They introduced using diapers (lint free and absorbent) to clean and polish lenses, and sewing machine bobbin technology to the waterproofing process. Employees were also given Vitamin A supplements to support their vision – needed for the precision work. Once military production of binoculars was underway, several hundred thousand pairs a year were made, and the Navy no longer needed to borrow them from the public.[51]

Left image

“Enlist Your Dog for Defense!” World War II patriotic postal cover promoting the War Dog program. Lithograph by Matthew J. Huss (Diana), Evanston, Illinois, 1943.

Credit: Collection of the National Postal Museum (2002.2035.205).

Right image

“Shep will show ‘em…” Detail from magazine advertisement for Sparton Precision Electrical outlining the price of freedom, ca. 1943. Ft. Hancock was designated a National Historic Landmark on Dec. 17, 1982. It is part of Gateway National Recreation Area.

Credit: Collection of the National Museum of American History (2017.3036.01).

Fido Goes to War

Before World War II, the US military was not convinced that dogs would be useful in war. Dogs were serving with other militaries, including the Germans, France, and Russia. After the Japanese attacked the US home front, civilians including those from the dog show world established the Dogs for Defense program.[52] They showed the benefits of dogs in wartime, and became the official dog recruiting organization for the US military. Owners volunteered over 40,000 pet dogs for wartime service.[53]

After meeting basic requirements and passing a preliminary physical, 18,000 of the volunteered pet dogs were sent to one of several Army training centers.[54] These were located in Nebraska, Virginia, Montana, Mississippi, and Maryland.[55] After the War, dogs were returned to their owners if possible. The rest were adopted out, with priority given to servicemen and families whose pets had been killed in action. Only a very small number of dogs could not be retrained for civilian life.[56]

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] Yates 1946: 79.

[2] Rockoff 2007: 3.

[3] Roosevelt 1942; United States Office of War Information c. 1944.

[4] Yale University Library n.d.

[5] Fishman and McKee 2015. The ways that lost recordings are found vary. For examples, see Dyer 2019; Graye 2022; Kenigsberg 2019; New School 2016; Townsend 2017; Watson 2020; Wexler 2022.

[6] Sundin 2011.

[7] Russell 1947a: 71; Sundin 2011.

[8] National Minerals Information Center n.d.

[9] Bailey 2017.

[10] Bailey 2017; Makamson 2017. Dayton is in Montgomery County, Ohio, an American World War II Heritage City. Several places have replaced or are beginning to replace monuments and cannons that they donated to the World War II metal drives (Bailey 2017).

[11] Sundin 2011.

[12] Sundin 2022a. Not only did the Girl Scouts of the USA (then known as the Girl Scouts of America) help collect metal during metal drives, but the organization changed their uniforms from fastening with zippers to fastening with buttons. This saved the metal needed for zippers for the war effort (Bamburg and Handley 2017).

[13] Russell 1947a: 83.

[14] Sundin 2022b.

[15] Ferdinand Eberstadt to Bernard Baruch, May 1942 in Provost 2022: 106.

[16] Sundin 2022b.

[17] Rockoff 2007: 29; Sundin 2022a, 2022b.

[18] Rockoff 2007: 28.

[19] Sundin 202a, 2022b.

[20] Provost 2022: 109-111; Rockoff 2007: 25.

[21] Provost 2022: 117.

[22] Rockoff 2007: 26.

[23] Oregon Secretary of State n.d.; n.a. c.1945.

[24] Sundin 2022a.

[25] n.a. c.1945; Sundin 2022a.

[26] Manitowoc Herald-Times 1941. Manitowoc, Wisconsin is an American World War II Heritage City.

[27] Sundin 2022a.

[28] Oregon Secretary of State n.d.; United States War Production Board ca. 1944.

[29] n.a. ca. 1945.

[30] Hunter 1944; News and Observer 1945. The same junk dealer was later sentenced for over a year in Federal prison for dealing in black market automobile tires.

[31] Russell 1947b: 233-234, 239.

[32] Ridner 2020.

[33] Braun 2014.

[34] Braun 2014; n.a. c.1943.

[35] Russell 1947b: 234, 242; Sundin 2022a. The program initially proposed paying 2 cents per pound.

[36] Russell 1947b: 234.

[37] Girl Scouts of the USA 2021; Russell 1947b: 247. See also Bamburg and Handley 2017.

[38] Rockoff 2007; Russell 1947b: 248.

[39] Alliance Times and Herald 1944; Kahler 2019.

[40] Albert 2022; Alliance Times and Herald 1944; BushTree 2013; Wykes 2014. Milkweed floss was also used in aviators’ suits and for thermal and acoustic insulation in aircraft.

[41] Alliance Times and Herald 1944; Timmons 1946: 218. Note: The Alliance Times and Herald article miss-states that 800 pounds of pods are needed for one pound of floss.)

[42] Albert 2022; Kahler 2019. The standard sized bag used was a mesh 50-pound onion sack. Each held approximately 1 bushel or 20 pounds of milkweed pods. The mesh helped the pods air dry and prevent rot (Albert 2022; Timmons 1946).

[43] Albert 2022; BushTree 2013; Kahler 2019. The Milkweed Floss Corporation of America was the only milkweed processing plant in the country. It was established specifically to process milkweed for World War II, and shut down once the conflict was over (Albert 2022).

[44] Kahler 2019.

[45] Rockoff 2007: 11.

[46] Girl Scouts of the USA 2021; Rockoff 2007: 11-12.

[47] Oregon Secretary of State n.d.

[48] Rockoff 2007: 3, 11.

[49] United States War Department 1918.

[50] Casper Tribune-Herald 1942. Casper, Wyoming is the county seat of Natrona County, an American World War II Heritage City.

[51] McKee 2020.

[52] Golden 2017; Kiser 2020; Paltzer n.d.

[53] Miller 1961: 616.

[54] Golden 2017; Kiser 2020; Miller 1961: 616; Paltzer n.d.

[55] Erlanger 1944; Miller 1961: 617; Paltzer n.d.; Smithsonian Institution n.d.

[56] Paltzer n.d.

Albert, Kaitlyn (2022) “Petoskey, Michigan and Milkweed: An Unsuspected Plant Aided in the War Effort During World War II.” Little Traverse Historical Museum, 2022.

Alliance Times and Herald (1944) “Milkweed Wanted for Life Jackets.” Alliance Times and Herald (Alliance, Nebraska) July 25, 1944.

Bailey, Ronald H. (2017) “Iron Will: Scrapping History.” HistoryNet November 27, 2017. Originally published in World War II Magazine August 2010.

Bamburg, Savannah and Lauren Handley (2017) “More than Prepared: Girl Scouts During WWII” See & Hear: Museum Blog, The National WWII Museum, February 17, 2017.

Braun, Adee (2014) “Turning Bacon Into Bombs: The American Fat Salvage Committee.” The Atlantic April 18, 2014.

BushTree, Howard (2013) “WWII Need for Milkweed Pods.” Charlevoix Emmet History – Honoring the Military.

Casper Tribune-Herald (1942) “Defense Notes: Navy Asks for Loan of Binoculars.” Casper Tribune-Herald (Casper, Wyoming) March 6, 1942, p. 4.

Dyer, Chris (2019) “Lost Martin Luther King Speech from 1967 is Discovered on an Old Recording by Rights Activist Who Also Taped KKK Members Threatening to Kill Him the Night Before.” Daily Mail, September 10, 2019.

Erlanger, Alene (1944) “The Truth About War Dogs.” The Quartermaster Review, March-April 1944. Reproduced at The Army Quartermaster Foundation.

Fishman, Karen and Jan McKee (2015) “Scrap for Victory!” Now See Hear! Blog of the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center, January 15, 2015.

Girl Scouts of the USA (2021) “Girl Scouts Provide Much-Needed Aid During World War II.” National World War II Museum, March 10, 2021.

Golden, Kathleen (2017) “Dogs for Defense: How Skip, Spot, and Rover Went Off to Fight World War II.” O Say Can You See: Stories from the Museum, National Museum of American History, August 17, 2017.

Graye, Megan (2022) “Desert Island Discs: Bing Crosby and David Hockney Among 90 Discovered Recordings.” The Independent, October 13, 2022.

Hunter, Marjorie (1944) “Two-Year Sentence Given Weinstein in Paper Cases.” The News and Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina) March 1, 1944, p. 1-2.

Kahler, Kathryn A. “Back In The Day: When Picking Mikweed Was A Patriotic Pursuit.” Wisconsin Natural Resources Magazine Fall 2019.

Kenigsberg, Ben (2019) “How Moon-Landing Tapes Found in a $218 Batch Could Fetch $1 Million.” New York Times, July 15, 2019.

Kiser, Toni M. (2020) “Dog Day Afternoon.” National World War II Museum, August 26, 2020.

Makamson, Collin (2017) “Billy Michal.” National World War II Museum, September 29, 2017.

Manitowoc Herald-Times (1941) “Paper Bundles Serve as Dance Tickets.” Manitowoc Herald-Times December 18, 1941. Collection of Manitowoc Public Library.

McKee, Timothy Brian (2020) “Mansfield Rises to Crisis: The Westinghouse Binoculars of WWII.” Richland County History, April 18, 2020.

Miller, Everett B. (1961) United States Army Veterinary Service in World War II. Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army, Washington, DC. Collection of the National Library of Medicine.

n.a. ca. 1945 “War Production Urgently Needs Waste Paper.” Collection of the Wisconsin Maritime Museum (M82-19-4. Box 87. World War II General G.C. “Buck” Weaver; File Ms34.1 Home Front).

--- (c. 1943) “Munitions from Kitchens.” Collection of the Oregon State Archives, Defense Council, Folder 8, Box 30. From Oregon Secretary of State (n.d.) Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II.

National Minerals Information Center (n.d.) “Iron and Steel Scrap Statistics and Information.” National Minerals Information Center, United States Geological Survey.

News and Observer (1945) “Weinstein Case.” News and Observer (Raleigh, North Carolina) May 4, 1945, p. 17.

New School (2016) “FOUND: Lost Recording of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Speech at The New School.” New School News, January 26, 2016.

Oregon Secretary of State (n.d.) “Salvaging Victory: Scrap Drives for the War Effort.” Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II.

Paltzer, Seth (n.d.) “The Dogs of War: The U.S. Army’s Use of Canines in WWII.” Army Historical Foundation.

Provost, Nyla (2022) “The Development of Synthetic Rubber and its Significance in World War II.” History in the Making 15: 103-125.

Ridner, Judith (2020) “The Dirty History of Soap.” The Conversation May 12, 2020.

Rockoff, Hugh (2007) “Keep on Scrapping: The Salvage Drives of World War II.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, Working Paper 13418.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. (1942) “Scrap Rubber Drive: Bing Crosby” (photograph). Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/195573

Russell, Judith (1947) “Processed Foods Rationing.” In Judith Russell and Renee Fantin (1947) Studies in Food Rationing, Office of Temporary Controls, Office of Price Rationing, p. 71-182.

--- (1947) “The Fat Salvage Campaign.” In Judith Russell and Renee Fantin (1947) Studies in Food Rationing, Office of Temporary Controls, Office of Price Rationing, p. 233-264.

Smithsonian Institution (n.d.) “World War II Patriotic Cover.” Smithsonian Institution.

Sundin, Sarah (2022) “Make It Do: Scrap Drives in World War II.” Today in World War II History, June 8, 2022.

--- (2022) “Make It Do: Tire Rationing in World War II.” Today in World War II History, January 5, 2022.

--- (2011) “Make It Do: Metal Shortages During World War II.” Today in World War II History, July 11, 2011.

Timmons, F. L. (1946) “Studies of the Distribution and Floss Yield of Common Milkweed (Asclepias Syraca L.) in Northern Michigan.” Ecology 27(3): 212-225.

Townsend, Mark (2017) “’Spine-Tingling’ Lost Bob Marley Tapes Restored After 40 Years in a Cellar.” The Guardian, February 4, 2017.

United States Department of Defense (1996) “View of the Marine Corps war dog cemetery built in memory of the twenty-five combat trained dogs that lost their lives in the bitter fighting for the liberation of Guam.” Photo by Dawn C. Montgomery, American Forces Information Service, Defense Visual Information Center. Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

United States Office of War Information (c. 1944) “Get In The Scrap!” Illustration by Walt Disney. United States Office of War Information. Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

United States War Department (1918) “Navy Request for Binoculars Brings Thousands.” Photograph by Harris & Ewing, November 19, 1918. United States War Department. Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration.

United States War Production Board (ca. 1944) “Paper Trooper: A Manual for School Administrators and Community Leaders.” Collection of Oregon State Archives, Defense Council Records, Folder 9, Box 30. From Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II.

Watson, Bridgette (2020) “Earliest Known Recording of Joni Mitchell, Thought Lost Forever, Found In BC Basement.” CBC News, September 14, 2020.

Wexler, Ellen (2022) “Stephen Sondheim’s Lost College Musical Was Found Hidden in Plain Sight.” Smithsonian Magazine, December 9, 2022.

Wykes, Gerald (2014) “A Weed Goes to War, and Michigan Provides the Ammunition.” MLive, February 4, 2014.

Yale University Library (n.d.) “The History of 78 RPM Recordings.” Yale University Library, Irving S. Gilmore Music Library.

Yates, Richard E. (1946) “The Procurement and Distribution of Medical Supplies in the Zone of the Interior During World War II.” War Department, Office of the Surgeon General, 31 May 1946.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front During World War IIMeat Rationing

The Home Front During World War IIMeat RationingMeat was on the ration list from March 1943 through November 1945, spurring Meatless Tuesdays, a thriving black market, and new recipes.

-

The Home Front During World War IIIllicit Trade and Black Markets

The Home Front During World War IIIllicit Trade and Black MarketsDespite rationing and other limits on goods during the war, some people figured out how to profit and get what they wanted outside the law.

-

Home Front Buildup to World War IIThe Draft and the Arsenal of Democracy

Home Front Buildup to World War IIThe Draft and the Arsenal of DemocracyWorld War II began on Sept. 1, 1939. In the US, the government implemented a peacetime draft and expanded manufacturing.

Tags

- engaging with the environment

- developing the american economy

- science and technology

- us in the world community

- world war 2

- world war ii

- ww2

- wwii

- home front

- homefront

- rationing

- military history

- music history

- entertainment history

- history of technology

- history of science

- transportation history

- foodways

- milkweed

- history of clothing

- dogs

- american world war ii heritage city program

- awwiihc

- indiana

- ohio

- wisconsin

- north carolina

- pennsylvania

- illinois

- michigan

- washington dc

- nebraska

- virginia

- montana

- mississippi

- california

- maryland

- wyoming

- dayton

- raleigh

- chicago

- billings

- japan

- petoskey

- mansfield

- evansville

- des moines

- iowa

- pittsburgh

- massachusetts

- boston

- indianapolis

- evanston

- new jersey

- fort hancock

- louisiana