Last updated: July 12, 2022

Article

Answering the Call: Burrill Smith and the 54th Massachusetts

When President Abraham Lincoln called for the raising of African American regiments during the Civil War, Black men from around the country traveled to Boston to enlist with the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment. This story map highlights the experiences of Burrill Smith Jr., one of the men who joined this historic regiment and continued to serve his community throughout his life. To explore additional stories, visit A Brave Black Regiment: The 54th Massachusetts.

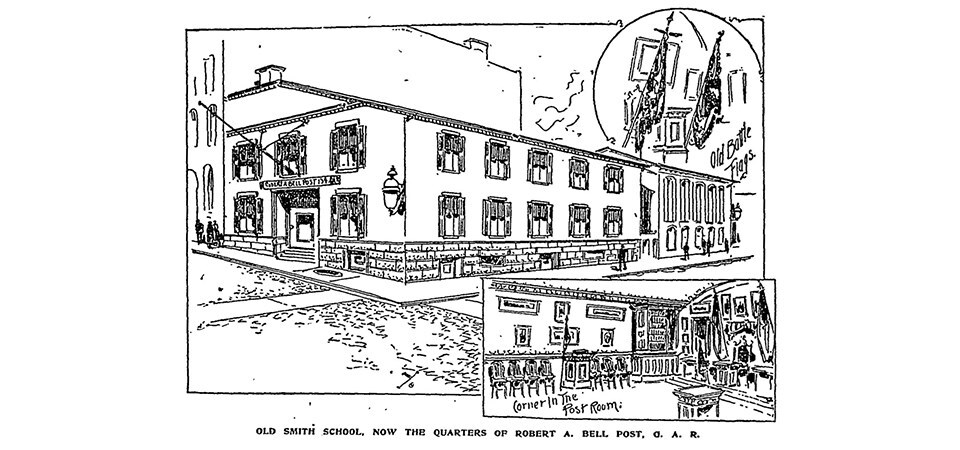

Born in Boston in 1846, Burrill Smith Jr. grew up in an abolitionist household. Continuing the activism of his parents, Smith became one of the first recruits in the historic 54th Massachusetts Regiment, one of the first African American regiments to fight for the United States during the American Civil War. Wounded at the Battle of Fort Wagner, Smith served until the end of the conflict. Following the Civil War, Smith joined the Robert A Bell Post, a G.A.R veterans' group and eventually served as its leader. He also remained politically active and established a reputation as a strong advocate for veterans of the 54th.

Explore the story map below to learn about Burrill Smith Jr.'s service during the Civil War and his contributions to his community after the war. Click "Get Started" to enter the map. To read more about each point, click "More" or scroll to view the map, historical images, and accompanying text. To navigate between the points, please use the "Next Stop" button at the bottom of the slides or the arrows on either side of the main image. To view a larger version of the main image depicted below the map, click on the image.

Footnotes

[1] Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Dr. Irving H. Bartlett collection, 1830-1880, W. B. Nickerson Cape Cod History Archives, 66-68, Archive.org.

[2] Kathryn Grover and Janine V. Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," Boston African American National Historic Site, (2002), 168.

[3] “Enlistment Roll of Company A, 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, 1863,” donated by John W. M. Appleton, Massachusetts Historical Society.

[4] “Burrill Smith’s Story,” Boston Daily Advertiser, May 24, 1897.

[5] Russell Duncan, Where Death and Glory Meet (Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1999) 89.

[6] Duncan, Where Death and Glory Meet, 103

[7] “The Brave Colonel Shaw,” The Sunday Herald (Boston, MA), May 30, 1897.

[8] “The Brave Colonel Shaw,” The Sunday Herald (Boston, MA), May 30, 1897.

[9] “The Brave Colonel Shaw,” The Sunday Herald (Boston, MA), May 30, 1897.

[10] Civil War Union Pension, Oct. 8, 1881. Burrill Smith Jr. (1” Sgt., Co. A, 54th MA Inf., Civil War), pension application no. 351,512, certificate no. 209.259, Case Files of Approved Pension Applications..., 1861-1934; Civil War and Later Pension Files; Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[11] Civil War Union Pension, Oct. 8, 1881. Burrill Smith Jr. (1” Sgt., Co. A, 54th MA Inf., Civil War), pension application no. 351,512, certificate no. 209.259, Case Files of Approved Pension Applications..., 1861-1934; Civil War and Later Pension Files; Department of Veterans Affairs, Record Group 15; National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[12] George Adams, Directory of the City of Boston, 1868 (Boston Athenaeum) p. 537.

[13] Massachusetts, U.S., Birth Records, 1866, Boston. No. 86., accessed through Ancestry.com; Massachusetts, U.S., Death Records, 1870, Boston. No. 56., accessed through Ancestry.com.

[14] “Oldest Colored Post,” Boston Globe, June 30, 1892.

[15] Barbara A. Gannon, The Won Cause, 35.; "Introduction," The Grand Army of the Republic and Kindred Societies, Main Reading Room. (Library of Congress)

[16] “Bell Post Veterans Imitate War-Time Festivities,” Boston Globe, April 2, 1889.

[17] “Election by Robert A. Bell Post, G.A.R.” Boston Globe, December 6, 1895.

[18] “To the Colored Citizens of Massachusetts and New England,” Boston Globe, August 17, 1872.

[19] “Voters Who Object to Cleveland Men and Their Complexion,” Boston Herald, August 17, 1888.

[20] “Burrill Smith’s Story,” Boston Daily Advertiser, May 24, 1897.

[21] “Burrill Smith’s Story,” Boston Daily Advertiser, May 24, 1897.

[22] “Veterans at his Bier,” Boston Herald, March 19, 1900.

[23] “Burrill Smith,” Boston Daily Advertiser, March 19, 1900.