Last updated: January 6, 2026

Article

The 54th Massachusetts and the Second Battle of Fort Wagner

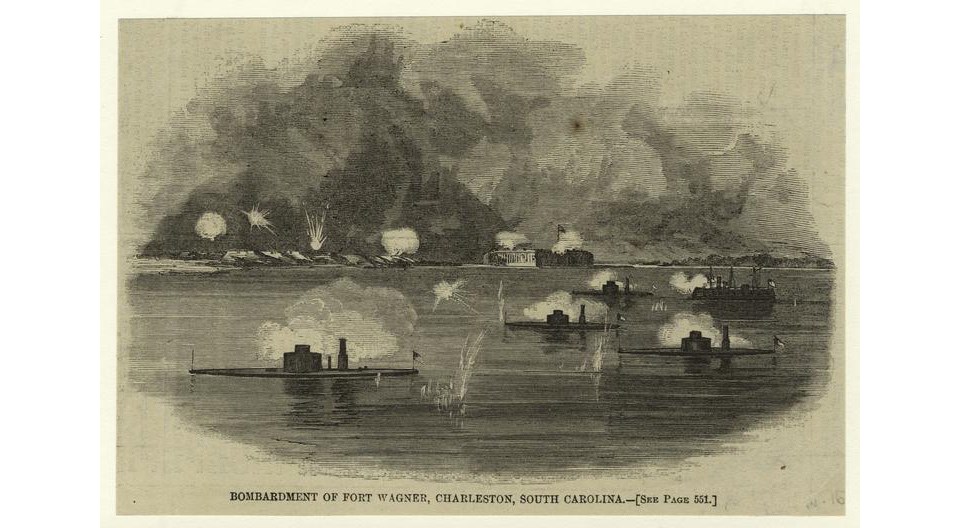

In July of 1863, the U.S. Army began their siege of the fortified Confederate city of Charleston, South Carolina. Redoubts and batteries surrounded the city. The formidable Fort Sumter guarded the entrance to the harbor, while Fort Wagner, located on Morris Island, commanded the southern portion of the harbor. That strategic location on the southern edge, however, also left Fort Wagner relatively vulnerable to Union assault.[1] If captured, Fort Wagner would provide the U.S. an opportunity to bombard Fort Sumter and provide access into Charleston harbor itself, an important step in securing the city that many saw as the birthplace of the Civil War.

U.S. forces stormed Morris Island on July 10, 1863. Assisted by a naval bombardment, the troops captured the southern portion of the island, but could not take Fort Wagner when the attack resumed the next day.[2] On July 18, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment led a second U.S. assault against Fort Wagner.

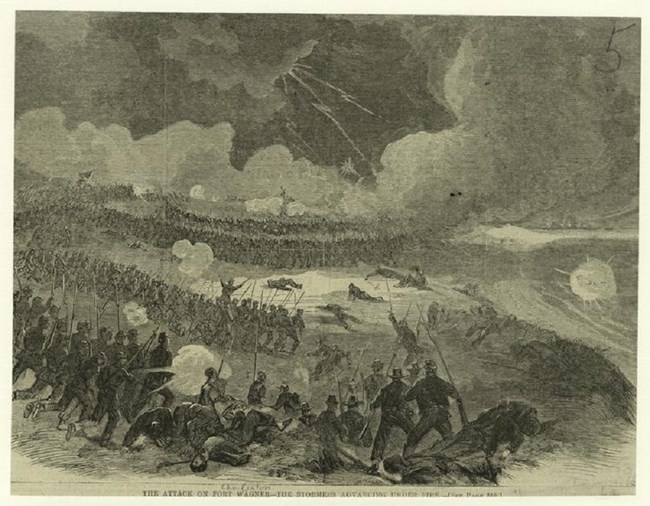

The Second Battle of Fort Wagner served as the 54th Massachusetts’s trial by fire. The all-Black volunteer regiment first experienced combat only two days prior in a comparatively minor skirmish.[3] The planned assault on Fort Wagner offered the regiment a chance to prove themselves, and their commander, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, jumped at the opportunity. The 54th’s assault on Fort Wagner became the first time the all-Black unit fought alongside White troops.[4] In addition, the 54th received the honor of leading the charge.[5]

Any regiment approaching the fort would certainly face heavy casualties. Approaching the fort required advancing up a strip of land so narrow only one regiment could attack at a time, preventing U.S. forces from effectively utilizing their superior numbers. The strip also lacked cover, making any attacking force an easy target for the Confederate soldiers defending Fort Wagner. The fort had artillery positioned to repel such a ground attack, with more artillery support coming from nearby fortifications, including Fort Sumter. The layout of Fort Wagner’s walls caused additional problems, as they allowed the Confederates to catch their attackers in a crossfire, making it difficult for the 54th to enter the fort.[6]

New York Public Library Digital Collections

To aid in the attack, U.S. ground artillery and naval guns bombarded Fort Wagner. The barrage lasted six hours, killing 8 and wounding 20 in a garrison of 1,700 Confederate soldiers. Unfortunately, the bombardment failed to damage the fort in any significant way and only served to alert the Confederate forces to the planned assault.

New York Public Library Digital Collections

As a result, the 54th Massachusetts assaulted an intact barricade, filled with readied Confederate troops. Newspaper correspondents later reported on the battle. One correspondent, writing for the Salem Register, wrote

...the men moved steadily amid a buzz and whirl of shell and solid shot, until within some three hundred yards of the fort. We could notice the ominous silence that preceded the storm; for a moment Wagner, Sumter, and Johnson were silent – then bang – zip zip – thud – crack went the most terrific discharges of musketry, grape, canister, solid shot, and every description of ammunition into our ranks, over our ranks, and through our ranks.[7]

Unable to fire back effectively, the 54th resolved to take the fort with bayonets. Under heavy fire, they scaled the parapet and forced the battle to shift to hand-to-hand combat. However, it quickly became clear that the 54th lacked the numbers and momentum to capture Fort Wagner. Rather than completely fall back, the 54th stayed close, providing covering fire for the other U.S. troops. After heavy fighting, the supplemental attacks also failed. The 54th ultimately withdrew with the rest of the U.S. forces and the regiment stationed themselves in a rifle trench in case of a counterattack.[8]

The counterattack never came. With the fighting over, two companies of the 97th Pennsylvania rescued as many wounded as they could. Special orders were given to save as many members of the 54th as possible. U.S. officers understood that, if captured, the African American soldiers of the 54th faced far worse treatment than any captured White soldier.[9] The battle devastated the 54th. Of the six hundred soldiers deployed, over 250 were killed, wounded, or captured, including Colonel Robert Gould Shaw.[10]

The members of the regiment lamented their heavy losses in letters home. One of the troops, Lewis Douglass, son of the famous abolitionist Frederick Douglass, wrote:

Saturday night we made the most desperate charge of the war on Fort Wagner, losing in killed, wounded and missing in the assault, three hundred of our men. The splendid 54th is cut to pieces…. If I have another opportunity tonight, I will write more fully. Goodbye to all. If I die tonight, I will not die a coward.[11]

New York Public Library Digital Collections

Despite the failure to capture Fort Wagner, the 54th Massachusetts made a profound impact. Journalists traveling with the army wrote about the assault and their comrades praised them wholeheartedly. General George Strong, a participant in the attack on Fort Wagner, said “…in all these severe tests, which would have tried even veteran troops, they fully met my expectations, for many were killed, wounded, or captured on the walls of the fort.”[12] Even the soldiers defending the Fort noted that the portion of the assault led by the 54th caused the most destruction. A Confederate officer wrote, “The greater part of our loss was sustained at the beginning of the assault, and in front of the curtain…”[13]

With the loss of the Second Battle of Fort Wagner, the Siege of Charleston slowed to a crawl. U.S. forces kept the fort surrounded for sixty days. The combined pressure of the blockade and constant skirmishing nearby forced the Confederate troops to abandon Fort Wagner. U.S. forces then occupied the fort, allowing for a sustained bombardment of both Fort Sumter and the city of Charleston.

For the 54th, the Second Battle of Fort Wagner catapulted them to fame. Storming the walls proved to the doubting nation that African American soldiers could fight. A correspondent of the New York Tribune reported, “It is absurd to say these men did not fight and were not exposed to perhaps the most deadly fire of the war, when so many officers and so many of the rank and file were killed.”[14] Public recognitions of the 54th’s bravery during the battle continued long after the war ended. William Harvey Carney received the Medal of Honor for saving the 54th’s flag when the color bearer fell. Despite his injuries, Carney protected the flag for the remainder of the battle. The 54th Massachusetts’ valor at the Battle of Fort Wagner paved the way for more African Americans to enlist. By the end of the war more than 180,000 African Americans enlisted in the U.S. Army, making up 10% of all U.S. forces for the duration of the war. Correspondents relayed the 54th Massachusetts’ heroism and devotion, even after their defeat. After visiting wounded members of the 54th, a writer for the New York Post reported “No man can pass among these sufferers…and not be inspired with the deepest abhorrence of slavery and an unquenchable desire for the freedom of their race.”[15]

Footnotes

[1] Roswell Sabine Ripley, “Correspondence Relating to Fortification of Morris Island and Operations of Engineers. Charleston, S. C., 1863,” South Caroliniana Pamphlet Collection, 1878, https://digital.tcl.sc.edu/digital/collection/sclpam/id/1281.

[2] Luis Fenollosa Emilio, History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1863-1865 (Boston: The Boston book co., 1891), http://archive.org/details/historyoffiftyfo00emil, 52-53.

[3] Emilio, 61.

[4] Emilio, 72.

[5] Emilio, 73.

[6] Emilio, 78-80.

[7] ”The 54th at Morris Island,” Salem Register August 3, 1863.

[8] Emilio, 81-85.

[9] Emilio, 103.

[10] Emilio, 91.

[11] Letter from Lewis Douglass to Frederick Douglass and Anna Murray Douglass, July 20, 1863. Transcribed in Freedom’s Journey: African American Voices of the Civil War, ed. Donald Yacovone (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books, 2004), p. 108-9.

[12] Emilio, 93-94.

[13] Emilio, 95.

[14] “Evening Star. [Volume] (Washington, D.C.) 1854-1972, July 28, 1863, Image 1, Br,” n.d.

[15] “The Daily Green Mountain Freeman. [Volume] (Montpelier, Vt.) 1861-1865, July 29,” n.d.