Last updated: January 6, 2026

Article

William H. Carney

Between two and three o’clock on the afternoon of December 11, 1908, the flags at the Massachusetts State House flew at half-staff.[1] The flag flew in honor and remembrance of the life of Sergeant William Harvey Carney of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment.[2] This day marked one of the first times in Massachusetts history that the honor had been given to an African American man.[3]

Born to William Carney Sr. and Ann Dean in Norfolk, Virginia on February 29, 1840, William H. Carney spent the majority of his boyhood enslaved. At the age of fourteen, he secretly began attending a private school led by a minister.[4] Carney learned how to read and write, defying unjust 1800s anti-literacy laws that made it illegal for anyone to teach African Americans. Through school, William Carney began studying the bible more deeply.

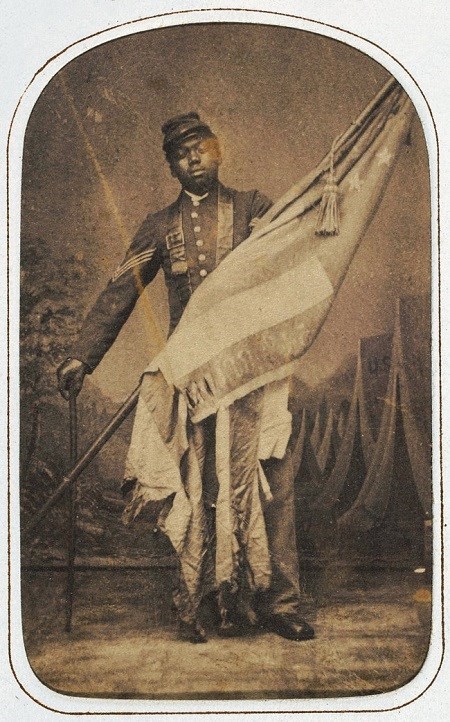

John Ritchie, Carte-de-vista album of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, 1864, album, National Museum of African American History and Culture.

William H. Carney's exact route to freedom is uncertain. Some accounts claim that he escaped on his own through the Underground Railroad and joined his father in Massachusetts, while others believe that Carney's father purchased his son's freedom after gaining his own through the Underground Railroad. The Carney family made their way to Massachusetts and settled in New Bedford where, after the death of her enslaver, Carney's mother joined them.[5]

Carney's secret education and religious conviction led him to consider a career in the church. However, in 1863, after the United States Army allowed African Americans to serve in combat roles, Carney's path changed. In a letter dated October of 1863, Carney wrote, "I had a strong inclination to prepare, myself for the ministry; but when the country called for all persons, I could best serve my God by serving my country and my oppressed brothers. The sequel is short – I enlisted for the war."[6]

William H. Carney, just twenty-three years old, joined the Morgan Guards in February of 1863. This Black militia, originally named for a White benefactor from New Bedford, changed its name to the "Toussaint Guards" one month after Carney joined. The new name "Toussaint" came from the leader of the Haitian Revolution, Toussaint Louverture.[7] The Haitian Revolution, a successful revolt of the enslaved population in Haiti, led to the abolition of slavery on the island and the establishment of the first Black Republic in the Americas. When Massachusetts called for Black soldiers, the Toussaint Guards soon joined with the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Carney served in Company C, and in March of 1863, he received a promotion to the rank of Sergeant.[8]

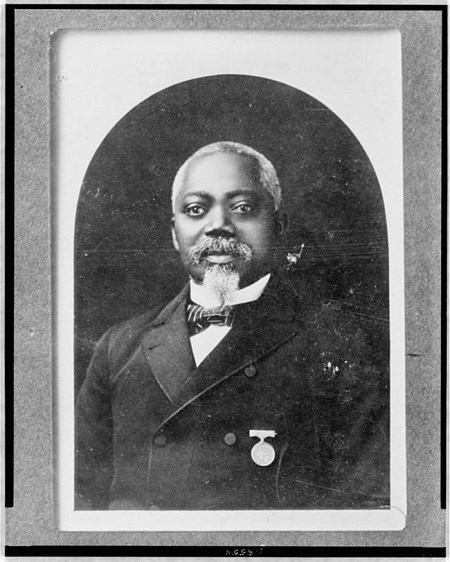

W.E.B. Du Bois Collector. "Sgt. William Carney, head and shoulders portrait, facing front., ca. 1900. Photograph."

On July 18, 1863, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment led the charge on Fort Wagner outside of Charleston, South Carolina under the command of Col. Robert Gould Shaw. When the unit's flag bearer fell after being shot down during the battle, Sergeant Carney retrieved the American flag and continued to march it forward "pressing his wound with one hand and with the other holding up the emblem of freedom."[9] Despite multiple serious wounds, Carney pushed forward and planted the flag upon the parapet.[10] When Union forces had to retreat Carney continued to carry the flag until he made it to friendly lines and handed it to another member of the 54th Massachusetts. Upon arriving at federal lines Carney cried, "Boys, I did but my duty; the dear old flag never touched the ground!"[11]

Sergeant William H. Carney received an honorable discharge from the United States Army in June of 1864 because of the injuries he sustained at the Battle of Fort Wagner.[12] He returned to New Bedford, Massachusetts where he found work as the state’s fourth African American postman, a position which he held for thirty-two years.[13]

Almost four decades after the battle of Fort Wagner, in May, 1900, Sergeant Carney received the Medal of Honor for his gallant actions. Carney is one of twenty-two African Americans to receive the medal for service during the Civil War and his actions are the earliest act of African American bravery to be recognized with the medal. African Americans who fought in the Union Army took an enormous risk. According to Captain Luis F. Emilio,“The hesitant policy of our government permitted the Rebels to confront every black solider with the threat of death or slavery. If he escaped the bullet and the knife, he came back to camp to learn that the country for which he had braved that double peril intended to cheat him out of the pay on which his wife and children depended for support.”[14] As a self-liberated man, Sergeant William H. Carney knew that fighting for the freedom of others could come at the cost of his own freedom. The Medal of Honor awarded to him reflects his courageous and meritorious actions that went above and beyond the call of duty.

Sgt. William H. Carney is in the second row, third from left.

"GAR Post 1 Members." Photograph. 1860. Digital Commonwealth

After leaving the postal service, Carney became a messenger at the Massachusetts State House. For forty-three years after the end of the Civil War, Carney continued to play an active role in Black veterans’ organizations. As a member of the Grand Army of the Republic Post 1, he attended reunions and battle anniversary memorials. In 1889, he even participated in a ceremony where he served as the featured singer of the Star-Spangled Banner.[15] In November of 1908, Sergeant Carney sustained fatal injuries from an elevator accident at the State House. Many accounts claim that Carney tried to courteously back out of the elevator to make room for others when the doors closed, and his leg became caught.[16] Sergeant William H. Carney lived a life of humble service and died at Boston City Hospital on December 9, 1908.[17]

Learn More

Footnotes

[1] “Dead Soldier Honored,” The Boston Globe, December 12, 1908.

[2] “Dead Soldier Honored,” The Boston Globe, December 12, 1908.

[3] Carl J. Cruz, “Sergeant William H. Carney, Civil War Hero” in It Wasn’t in Her Lifetime, but It Was Handed Down: Four Black Oral Histories of Massachusetts, ed. Dr. Eleanor Wachs (Office of Massachusetts Secretary of State, 1989) 10.

[4] “Interesting Correspondence,” The Liberator, November 6, 1863.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Matthew J. Clavin, Toussaint Louverture and the American Civil War: The Promise of Peril and a Second Haitian Revolution, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 125-126.

[8] The National Archives at Washington, D.C, Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the U.S. Colored Troops, 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Microfilm Serial: M1898; Microfilm Roll: 3. Accessed through ancestory.com.

[9] “The Mass 54th at Fort Wagner,” The Liberator, August 28, 1863.

[10] Luis F. Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment: History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry 1863-1865, (New York: Bantam Books, 1992) 88.

[11] “The Mass 54th at Fort Wagner,” The Liberator, August 28, 1863.

[12] The National Archives at Washington, D.C, Compiled Military Service Records of Volunteer Union Soldiers Who Served with the U.S. Colored Troops, 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, Microfilm Serial: M1898; Microfilm Roll: 3. Accessed through ancestory.com

[13] “Carney, William Harvey,” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College, http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/32470.

[14] Emilio, A Brave Black Regiment, 33.

[15] “Freedom Unforgotten,” The Boston Globe, July 25, 1889.

[16] Sergt W.H. Carney’s Leg Crushed in Elevator,” The Boston Globe, November 23, 1908.

[17] "Massachusetts Deaths, 1841-1915," database with images, FamilySearch, William H Carney, 09 Dec 1908; citing Boston, Massachusetts, 732, State Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 2,217,886.