Part of a series of articles titled Intermountain Park Science 2021.

Article

A New Way of Documenting and Imaging Cultural Resources

- Katherine Shaum, Archeological Technician, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, National Park Service (currently Archaeologist, Tonto National Forest, United States Forest Service)

- Neil Dixon, Owner, The Front Standard Photography

Summary

In 2018, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument received a grant from the Western National Parks Association to better document its cultural resources. This grant included funding for a small project that involved conservation and cleaning of the interior walls of the Great House, a 14th century Hohokam multi-story earthen structure that is the centerpiece of the park, followed by reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) photography. The purpose of this project was to better document the physical condition of plaster decorations inside the Great House and also, potentially, identify previously unknown elements in the areas surrounding them.

NPS photo.

Introduction

The Hohokam archaeological culture existed in southern Arizona from roughly A.D. 450 to A.D. 1450. The Great House at Casa Grande Ruins NM has been called “the pinnacle of Hohokam architectural achievement” (Doelle 2009) (Figure 1). Archeological research and historic accounts suggest there may once have been 12 such “Great Houses” in the Phoenix Basin, but today the Great House at Casa Grande Ruins NM is the only one that remains standing and available for public visitation.

The Great House is a monumental 11 room, three to four story structure made of puddled mud with a high calcium carbonate component. It was likely built around A.D. 1325 and was no longer used on a permanent basis by A.D. 1450. Despite its status as the centerpiece of its park, there is much that remains mysterious about the Great House.

Stacks A, B, D, and E each contained two inhabitable floors, while Stack C contained three inhabitable floors (Figure 2). Small openings represent windows/observation points and large openings represent doorways.

The interior of the Great House was closed to visitors in the 1970s because of concerns about the building’s structural integrity and the effect of frequent unmonitored visitation inside such a resource. Visitors today can still look into the Great House from two doorways, but there is no visibility into Stack C, the center room of the Great House where plaster preservation is greatest. Indeed, the Great House as a whole is significant for this high degree of preservation. Stabilization efforts have taken place over the years, most notably in the 1890s, but, nevertheless, the Great House is 90 percent original (NPS, A. Hayes, Chief of Resource Stewardship and Facilities Management, personal communication, 2018).

The nature of all exposed surfaces in the environment is to erode. The wall surfaces inside the Great House do have the added protection of a roof shelter, constructed in its current form in 1932. This protection, however, also created a disadvantage by creating a shaded habitat for various bird populations. The plaster surfaces of the Great House are therefore exposed to added damage from acidic bird droppings.

In addition to the tall, tapering, caliche-rich walls, there are intact earthen plasters and washes with a pink hue inside the building. These plasters are technologically unique in that they possess a coat rich in calcium-phosphate, and also a gypsum finish coat that conveys a “polished” effect. There are also three known “plasterglyphs” (also called “mortar glyphs” or simply “glyphs”) on wall surfaces inside the Great House. These plasterglyphs are wall art that were seemingly drawn into the wet wall surface before it dried, or pecked or scratched into an already dry wall surface. In recent years, it has been debated whether these plasterglyphs date to the time of prehistoric occupation (A.D. 1325 – 1450), whether they are the work of prehistoric migrants who came after A.D. 1450, or whether they are historic (created after A.D. 1694, when Father Kino became the first documented European to visit the Great House). Mural art in the Hohokam world is extremely rare -- only a couple instances of it have ever been documented and all those were also at Casa Grande Ruins NM.

Prior to this project, these plasterglyphs had never been extensively documented. Located as they are on the second level of the Great House, they are difficult to study in detail because they are approximately 10 feet above the the floor surface. In addition, the tall walls of the Great House and the presence of the roof shelter make light conditions inside the building subpar for both photography and in-person inspection. As such, the purpose of this project was to better document the physical condition of these plaster decorations and also, potentially, identify previously unknown elements in the areas surrounding them.

Cleaning Wall Surfaces in the Great House

Some walls of the Great House are covered in bird excrement from resident Rock Pigeons (Columba livia), European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris), and Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus). When exposed to water, this excrement can dissolve plasters, cause acid etching, dissolve existing salts, and generate new salts that can cause staining. It also obscures underlying decorations and clues about the building’s construction.

The first step in obtaining detailed high resolution images of the three plasterglyphs in the Great House was to gently clean each, as well as the areas around them. Experienced conservators Angelyn Bass (Research Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico) and Doug Porter (Research Assistant Professor, School of Engineering, University of Vermont), who have worked in the Great House before, were joined by graduate student Katie Williams (Ph.D. Candidate, Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico) in undertaking this process. Using scaffolding, the conservation team dry-cleaned surface accretions of excrement using tools such as bamboo skewers and porcupine quills. These tools are softer than underlying plasters and therefore won’t damage them. For particularly heavy accretions, the team also employed damp cotton swabs for softening prior to treatment.

Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) Photography in the Great House

RTI photography is an extension of typical digital photography in a number of ways. It was first developed by Hewlett Packard Labs in 2001 as a method of mapping multiple light positions onto a computer-generated image at the pixel level (Malzbender et al. 2001). As this technology advanced, there were additional capabilities. Today, after photographs are taken and processed, a user can view an image in an associated software program and adjust the contrast and lighting angle. These adjustments can intensify subtle surface information and allow users to see details that cannot be seen in field environments with the naked eye.

In RTI photography, the photographer takes multiple digital photographs of a subject from a stationary camera position and applies light from different, but known directions. In our case, we used a specially designed hemisphere with fixed light sources. A total of approximately 48 shots of each panel of interest were captured and, with the use of reflective targets, each image was mathematically combined to create light position data and color data for each pixel in the image.

NPS photo/Neil Dixon.

These images were then “knit” together into one digital file that features a static image and a variable light source. In the RTI Viewer software program, the light source is universally adjustable by the user and includes overhead light and raking light from any side and on any area of interest. This image file can also be enhanced to bring unnoticed surface details into view – details that are often not visible on location due to poor lighting and subtle surface variation.

NPS photo/Neil Dixon.

The mathematical equation which gives each pixel its variable lighting also allows for enhancement through adjustment of color and specularity, or the amount of reflection a surface has. This is especially useful in archaeology when one needs to look at objects with low-relief etching or carving, as is the case with plasterglyphs, petroglyphs (images that are carved into rocks), dendroglyphs (images that are carved into tree trunks), wall murals, historic graffiti, headstones, and certain artifacts. Users may be able to see additional inscriptions, for example, or, in an overlapping situation, form improved conclusions about which inscriptions came first (Mudge et al. 2006).

NPS photo/Neil Dixon.

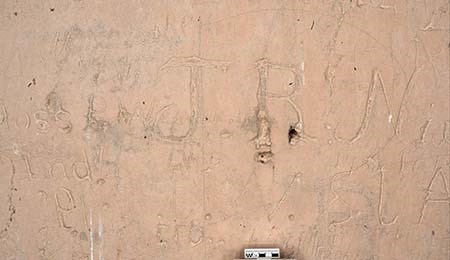

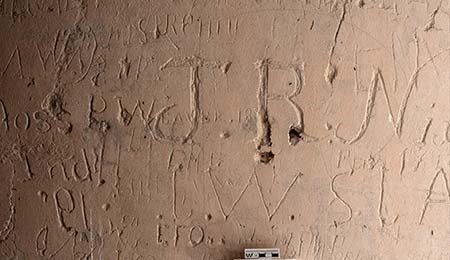

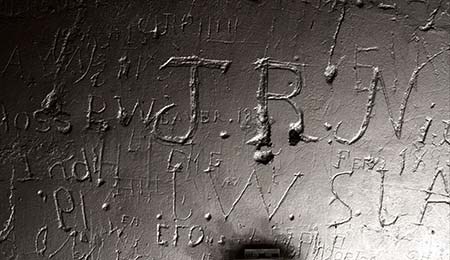

Using a 36-megapixel camera and an electronic flash unit operated by an assistant, we photographed all newly-cleaned wall surfaces, including those surfaces with plasterglyphs. We also photographed several wall panels covered in historic graffiti from overly enthusiastic visitors in the second half of the 19th century (Figures 3-5). This graffiti largely dates from the 1870s through the 1890s, after the railroad and a stagecoach route came to the local area, but before Casa Grande Ruins NM became a protected place with an on-site steward. In Figures 3-5, the inscription "P. Weaver" may stand for Pauline Weaver, a "mountain man" and fur trapper who operated along the nearby Gila River. It is difficult to see this inscription under normal conditions.

NPS photo/Neil Dixon.

Lastly, we photographed several artifacts with low-relief designs, such as decorated shell ring fragments and prehistoric ceramic comals (flat griddles typically used for cooking in Mexico and Central and South America) (Figures 6 and 7). Once captured, still images were post-processed and RTI images were completed. All files were then transferred to Casa Grande Ruins NM staff for their use.

NPS photo/Neil Dixon.

This documentation digitally preserved these glyphs and artifacts by helping mitigate, as it were, their ongoing erosional damage from animal and weather sources. Staff and volunteers can also use high quality, high resolution images to form new museum exhibits and create new 2D interpretive materials. An added benefit of RTI photography over typical digital photography is that the end product is a “manipulatable” image that exceeds both typical photography and on-site visits in quality and data potential. After post-processing, still images or dynamic files can be shared with researchers, negating their need to visit a fragile resource. With the proper equipment and technological know-how, parks and museums also have the potential to harness the dynamic component of RTI photography to create interactive interpretive displays or kiosks for visitors.

Conclusions

Although the RTI photography process did not bring to light any previously unknown plasterglyphs in the project area, the photographs generated as part of this project have rekindled interest in the plasterglyphs and other interior surfaces of the Great House. The photographs have been featured in historic research about Frank Lloyd Wright and the rock art of southern Arizona that inspired him. The photographs have also aided research about prehistoric migrations and trade connections as well as the overall tribal consultation process as Casa Grande Ruins NM completed its Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, an important baseline document. Lastly, the photographs could be incorporated into new interpretive materials such as a photography exhibit, visual aids for walking tours, and more.

For better documenting and understanding certain cultural resources, RTI photography can be a useful tool. It does, however, require advanced photographic equipment and knowledge. It may be best to hire an experienced photographer to obtain high quality RTI photographs. For those interested in learning more hands-on, the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT) will likely offer a course on RTI photography and other innovative photography techniques in the near future. [This training was scheduled for June 2020, but was cancelled due to the pandemic. NCPTT courses are open to NPS staff and other interested professionals]. To learn more about RTI photography virtually, please refer to Cultural Heritage Imaging's website at http://culturalheritageimaging.org/Technologies/RTI/ (accessed August 6, 2020).

References

Doelle, W. H. 2009.

Hohokam heritage: the Casa Grande community. Archaeology Southwest 23(4):1.

Malzbender, T., D. Gelb, and H. Wolters. 2001.

Polynomial texture maps. Pages 519-528 in Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, New York, New York.

Mudge, M, T. Malzbender, C. Schroer, and M. Lum. 2006.

New reflection transformation imaging methods for rock art and multiple-viewpoint display. Pages 195-200 in M. Ioannides, D. Arnold, and F. Niccolucci, editors. Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Cultural Heritage. Nicosia, Cyprus.

Last updated: September 13, 2021