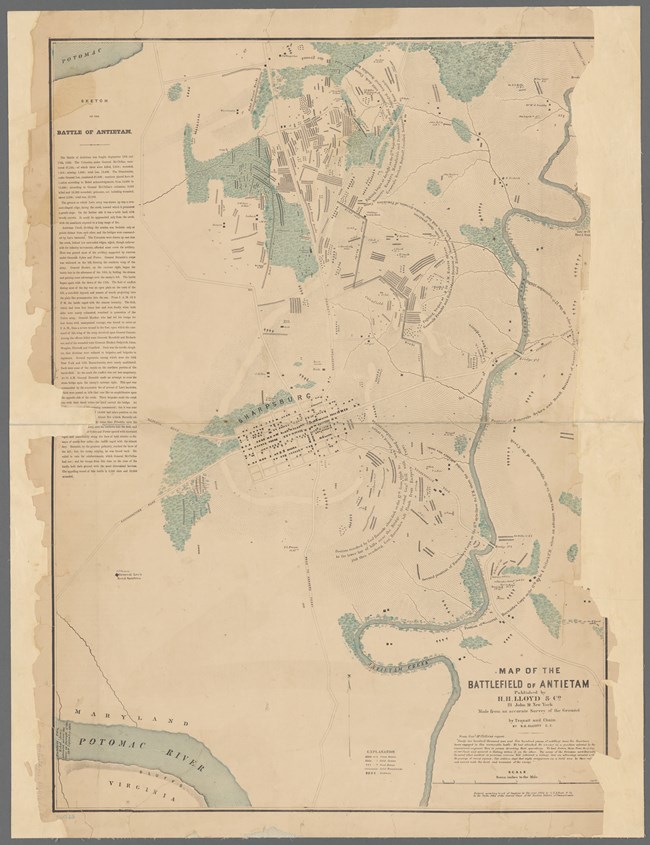

From The New York Public Library New DiscoveryIn the spring of 2020, researchers at the Adams County Historical Society, discovered a map at the New York Public Library, that displays the gruesome result of the Battle of Antietam. Two years after the battle, in 1864, S.G. Elliott drafted a map of the Antietam Battlefield that marked over 5800 graves of Union and Confederate soldiers, as well as gathering places that marked where horses were brought to be burned. This remarkable resource confirms much of what we know about the locations of burial trenches from Alexander Gardner's battlefield photos and period sketches. It also raises many new questions for Antietam scholars.

NPS Antietam Battlefield BurialsShortly after the battle, two local men from the Sharpsburg area, Aaron Good and Joseph Gill mapped the grave locations of those buried after the Battle of Antietam. By 1865 they had "a large number of names and carefully prepared register of the location of various graves." It was their list that assisted with the grisly task of removing the remains from the field to the newly established Antietam National Cemetery in late 1866. By the time of the cemetery dedication on the fifth anniversary of the battle, over 4200 Union soldiers had been re-interred, over 3200 from the battlefield.The number, 4200, not only includes the dead of Antietam but also Union Civil War soldiers that had been buried in Washington, Frederick, & Allegany Counties in Maryland. The History of Antietam National Cemetery also states that many of the soldiers from Maryland had been removed from the battlefield by family members and taken back to local cemeteries. It also should be noted that Pennsylvania and other states had removed a great many of their dead prior to the establishment of the National Cemetery. There are no marked Confederate graves in the Antietam National Cemetery. Following the battle, Confederates remained in the fields until approximately ten years later. By the end of 1872, over 1700 Confederate soldiers had been removed from the battlefield to Rose Hill Cemetery in Hagerstown, Maryland. The dedication of the Confederate section of this cemetery took place in 1877, a total of almost 2300 killed at Antietam and South Mountain were re-interred in Rose Hill.

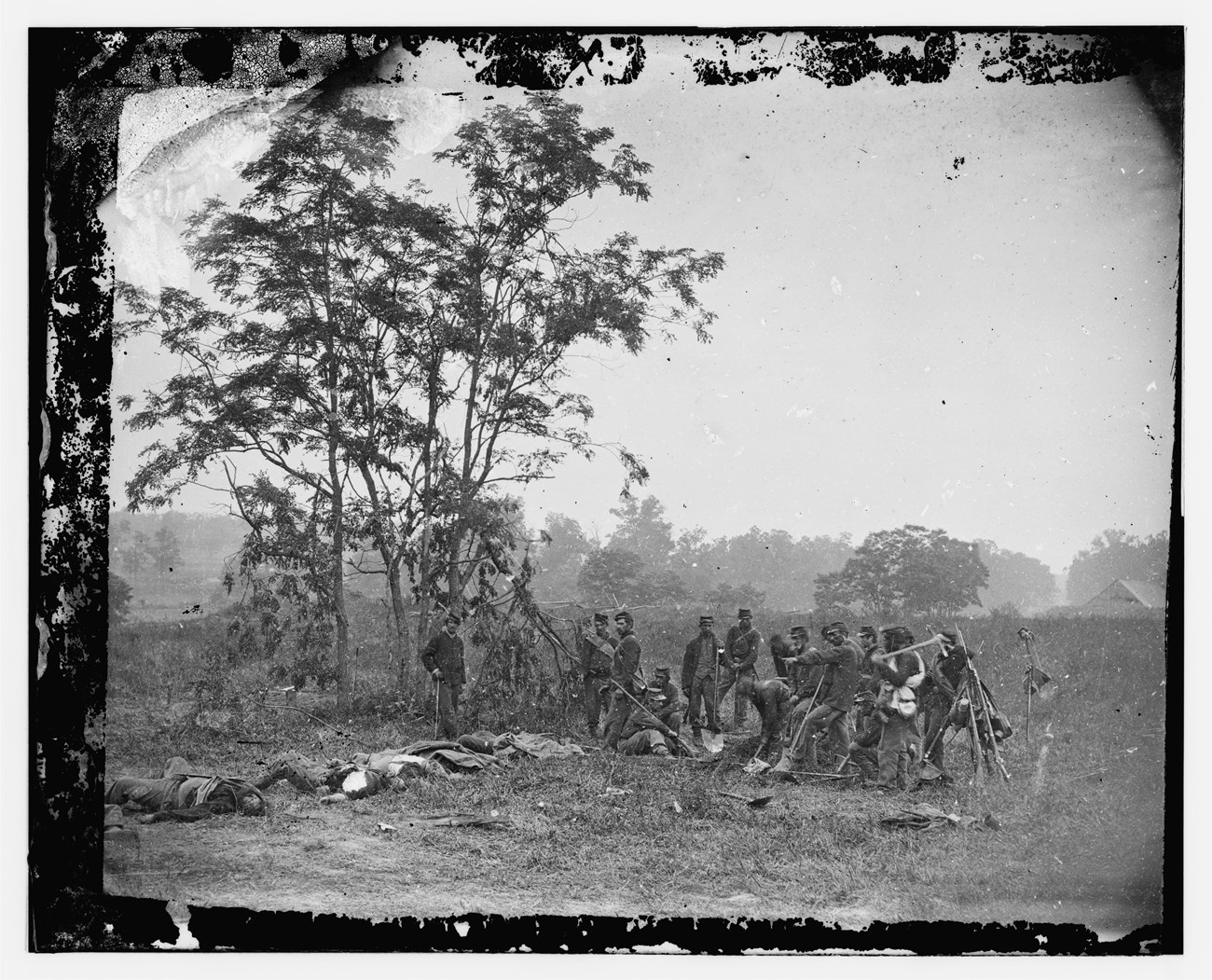

Library of Congress Union Burial DetailFollowing Lee's retreat from Sharpsburg, Union soldiers were left to bury their own first, and then buried the Confederates. This image above, taken by Alexander Gardner, depicts one of these burial parties in the middle of this horrific task. Under close inspection, photographic historian William Frassanitio determined these men were on the west side of the Hagerstown Pike, the top of the Miller Barn roof visible along the right side of the image was a key detail.

From New York Public Library

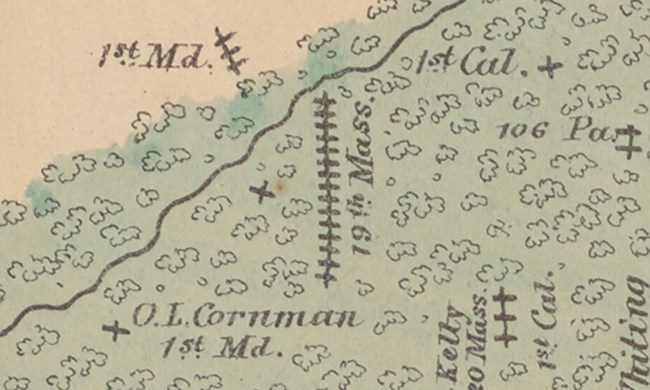

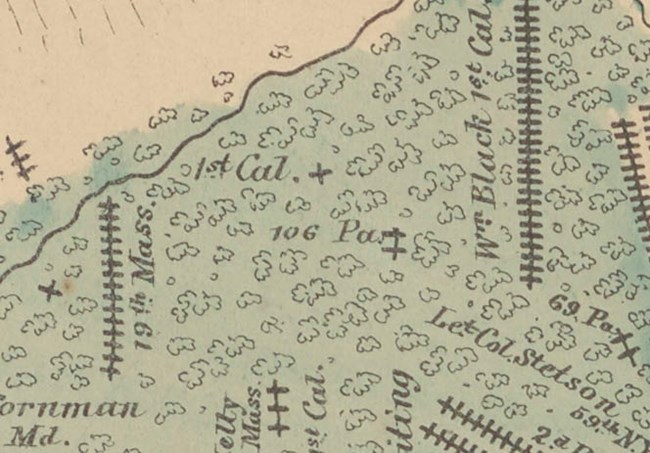

From New York Public Library O.L. Cornman, 1st Minnesota InfantryAs one could imagine, an undertaking such as the Elliott Antietam Map, mistakes were made. That was the case for the graves listed in the West Woods for three men from the First 'Maryland' and the lone grave of O.L. Cornman. There was no 1st Maryland Infantry Regiment in the Union Army at Antietam. That said, the First Minnesota was engaged at Antietam and they fought within yards from where the graves are located on the map.On Sept. 30, 1862 in the Stillwater Messenger, the location of Oscar's grave was described. "Corporal Cornman's body was interred by company B, apart from all the others, in a beautiful grove near the battlefield. May it rest undisturbed by the clangor of battle until the great Day when kindred and friends and comrades shall meet to separate no more forever." Today, Cpl. Oscar L. Cornman rests in the Antietam National Cemetery.

From New York Public Library 106th Pennsylvania InfantryPvt. Elwood Rodebaugh was a shoemaker from Canton, Pennsylvania. His regiment was part of the action in the West Woods where 2200 out of 5300 Union soldiers were killed or wounded in about twenty minutes of action on the morning of the battle. His friends remembered the last time they saw him that morning was as the regiment rallied along a fence line during the fierce action on this part of the field. They went on to say that because he had recently shaved off his beard he was unrecognizable by the burial parties in the days following the fight. Today, he is buried in the Unknown section of the Antietam National Cemetery, but does the two single graves marked 106 PA possibly show where Elwood was initially buried? Even though some questions can't be answered fully, this map is another piece of the puzzle researchers can use to learn more about their ancestors.

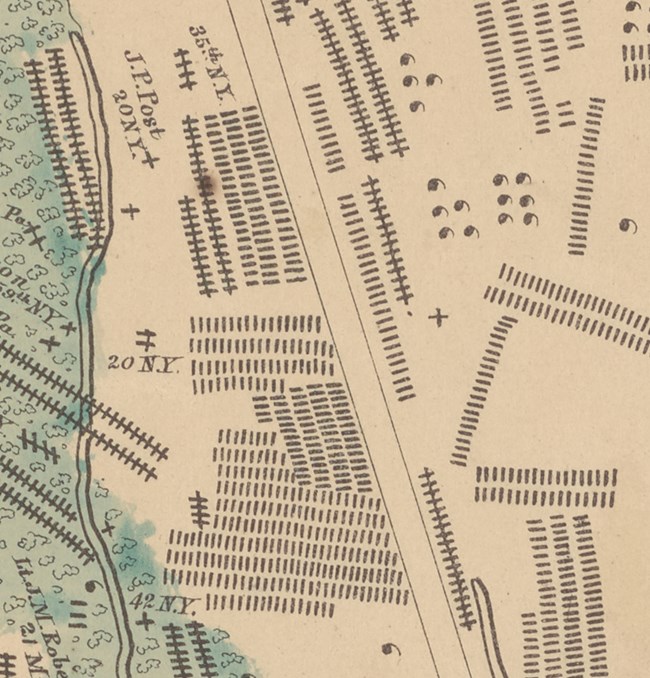

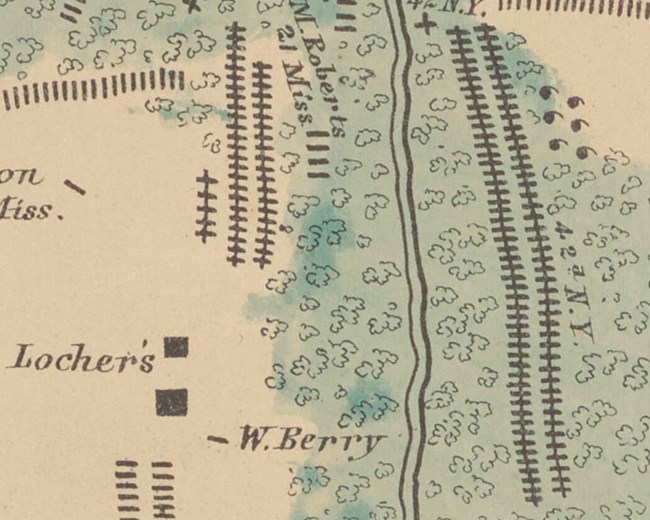

From The New York Public Library 15th MassachusettsIt appears the only mention of the 15th Massachusetts on the Elliott Map, would be a few lone graves near the East Woods. This regiment saw their heaviest fighting in the West Woods, where they were caught in a terrible crossfire and lost 117 killed. Another regiment swept up into the Union disaster in that part of the field was the 42nd New York, who lost 41 killed.The Elliott Map labels a group of two long rows, consisting of 95 Union soldiers, in essentially the exact potion held by the 15th Massachusetts in the West Woods. We know with certainty they aren't all from the 42nd NY since that regiment only lost 41. Is it then possible that this grouping is the burial location of the men from Massachusetts and not New York?

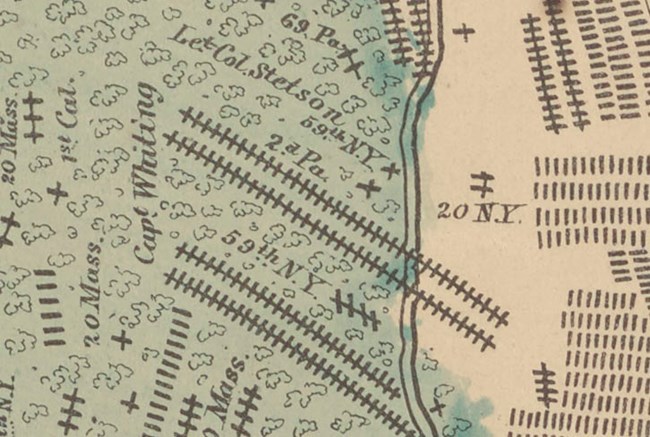

NPS Antietam/ K.Snyder Lt. Col. John L. StetsonPart of a letter by his father telling the details of going to the field to find his son:Baltimore, September, 27, 1862. I found the burial rude and imperfect, like all soldiers' graves upon the field. On Tuesday morning I returned from Sharpsburg with a burial party, and had a wall twenty inches high built around the grave, close to the vault. This was filled with fresh earth and raised above the wall, and completed in the usual form. Then along the sides to the crest I laid slabs of dark brown limestone, at at the head and foot stand heavy stones trenched into the ground. Over the whole I lad green boughs cut from the top of the white oaks felled by the cannon shot, nearby. The duty was ended; the burial was complete--complete as might be under an exigency, which cannot be understood without too long an explanation--and I stood among strangers,--the rank and file of the army,--to make my grateful heartfelt acknowledgments for their kind assistance.

From The New York Public Library But I am departing from my purpose--the curse of mankind--war, is upon us; and yet it is only by war--vigorous, earnest, resolute war to the knife,--war in the minds and hearts of our people at home, as we see and feel the horrors of the front, and in the track of battle, that can save our nationality and preserve to us, or recover for us, the decent respect of mankind. The conduct of Colonel Tidball, and Major Northedge, of the 59th, is described as gallant and resolute in the action of the 17th. The regiment went into action with less than 400 men. It lost in killed 47; wounded 143; 13 of 21 officers were killed or wounded. Respectfully yours, L. Stetson.

Alexander Gardner Pvt. John Marshall, 28th Pennsylvania InfantryOn the Elliott Map of Antietam burials, there are fifty individual graves marked. Typically if a soldier was able to get to the field before the burial parties and find a friend they would have marked the location with a headboard. In the days following the battle, Alexander Gardner traveled across the Antietam battlefield and photographed the aftermath of the bloodiest day in the history of the United States. These photos survive today at the Library of Congress.After magnifying some of these photos, photographic historian, William Frassanito published a book, “Antietam: A Photographic Legacy of American’s Bloodiest Day” showing the reader the locations around the field where Gardner captured his famous images. Upon closer examination, Frassanito discovered in some of the photos that included headboards, a name was legible.

The New York Public Library The image above is of the grave of Pvt. John Marshall. Frassanito determined the location of the photo/gravesite by using the unusual rock features that are prominent behind the grave. After enlarging the photo the name on the headboard is that of Marshall. Because of the discovery of the Elliott Map of Antietam, historians and researchers can see on this map the location of grave confirming without question the location of one of the most haunting images of the aftermath of Antietam. |

Last updated: December 31, 2024