The Year Maine BurnedAfter a long Maine winter, spring is always eagerly anticipated. This was especially true in 1947; the gloominess of World War II still lingered and everyone looked towards the weather to lift their spirits. It rained continually through April, May, and most of June. Finally, at the end of June, the sun came out, temperatures soared, and summer finally emerged. But weather patterns continued to be odd that year. Through the summer and into the fall, Maine received only 50% of its normal rainfall. Vegetation became bone dry and water supplies dwindled. Most residents did not worry and assumed rain would come eventually. The island enjoyed one of the most beautiful Indian summers in memory. But the autumn rains never came, and by mid-October, Mount Desert Island was experiencing the driest conditions ever recorded. The stage was set for a disastrous blaze.

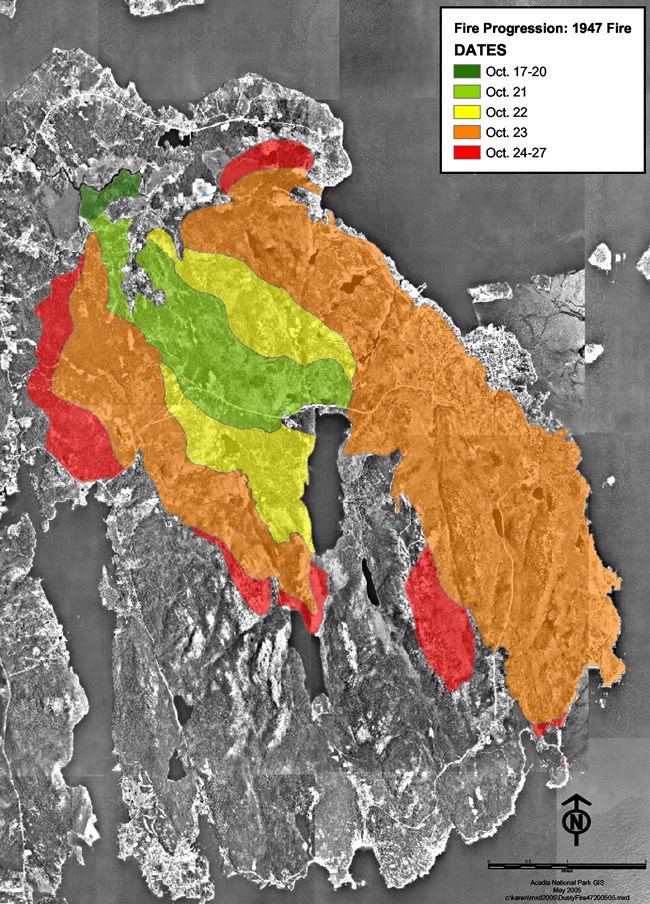

NPS The Great FireOn Friday, October 17, 1947, at 4 p.m., the fire department received a call from Mrs. Gilbert, who lived near Dolliver’s dump on Crooked Road west of Hulls Cove. She reported smoke rising from a cranberry bog between her home and the dump. No one knows what started the fire. It could have been cranberry pickers smoking cigarettes in the bog. Or perhaps it was sunlight shining through a piece of broken glass in the dump that acted like an incendiary magnifying glass. Whatever the cause, once ignited, the fire smoldered underground. From this quiet beginning arose an inferno that burned nearly half of the eastern side of Mount Desert Island and made international news. In its first three days, the fire burned a relatively small area, blackening only 169 acres. But on October 21, strong winds fanned the flames. The blaze spread rapidly and raged out of control, engulfing over 2,000 acres. Personnel from the Army Air Corps, Navy, Coast Guard, University of Maine forestry program, and Bangor Theological Seminary joined local firefighting crews. National Park Service employees flew in from parks throughout the East and additional experts in the West were put on standby. The pace of the blaze intensified, and nearly 2,300 acres burned on October 22. The fire crossed Route 233 and continued along the western shore of Eagle Lake. On the morning of October 23, the wind shifted, pushing one finger of the fire toward Hulls Cove. Firefighters shifted their efforts in an attempt to squelch the threat to that community. But in the afternoon, the wind suddenly turned again and increased to gale proportions as a dry cold front moved through, sending the inferno directly toward Bar Harbor. In less than three hours the wildfire traveled six miles, leaving behind a three-mile-wide path of destruction. The fire swept down Millionaires’ Row, an impressive collection of majestic summer cottages on the shore of Frenchman Bay. Sixty-seven of these seasonal estates were destroyed. The fire skirted the business district, but razed 170 permanent homes and five large historic hotels in the area surrounding downtown Bar Harbor. Bar Harbor residents not actively engaged in firefighting tried to find safety, fleeing first to the athletic field and later to the town pier. At one point all roads from the town were blocked by flames, so fishermen from nearby Winter Harbor, Gouldsboro, and Lamoine prepared to help with a mass exodus by boat. At least 400 people left by sea. Finally, by 9 p.m., bulldozers opened a pathway through the rubble on Route 3 and a caravan of 700 cars carrying 2,000 people began the slow trip to safety in Ellsworth. According to eyewitness reports, it was a terrifying drive—cars were pelted by sparks, and flames flickered overhead. But the motorcade was orderly and successful, an uplifting end to a day that saw close to 11,000 additional acres blackened. Still the fire continued to burn. From Bar Harbor, the blaze raced down the coast almost to Otter Point, engulfing and destroying the Jackson Laboratory on its way. The fire blew itself out over the ocean in a massive fireball. But that wasn’t the end of the destruction. Almost 2,000 more acres burned before the fire was declared under control on October 27. Organic soil and vegetation on the forest floor, along with matted tree roots infiltrating deeply around granite boulders, aided stubborn underground fires. Even weeks later, after rain and snow had fallen, fire still smoldered below ground. The fire was not pronounced completely out until 4 p.m. on November 14, nearly one month after it began. News BroadcastsListen to a NBC news broadcast covering the Bar Harbor Fire of 1947:

Courtesy National Park Service/Acadia National Park The Lasting EffectsBy the end, 17,188 acres burned and more than 10,000 acres were in Acadia National Park. Property damage exceeded $23 million dollars. Considering the magnitude of the fire, loss of human life had been minimal. An elderly man returned to his home to save his cat and was never seen alive again. A car accident claimed the lives of an air force officer and a local teenage girl. A man and woman, already ill, succumbed to heart attacks. An unknown number of animals died in the blaze, but park rangers believe that most outran the fire and found safety in ponds and lakes. Once the fire was over, it was time to start anew. Two crews, one hired by the park and one hired by the Rockefeller family, logged selected park areas for timber salvage and clean-up. Some timber was milled, slash was burned, and other logs, still visible today, were left to prevent soil erosion. Nature, however, played the predominant role in the island’s restoration. The forests that exist today regrew naturally. Wind carried seeds back into burned areas, and some deciduous trees regenerated by stump sprouts or suckers. Today’s forest, however, is often different than what grew before the fire. Spruce and fir that reigned before the fire have given way to sun-loving trees, such as birch and aspen. But these deciduous trees are short-lived. As they grow and begin to shade out the forest floor, they provide a nursery for the shade-loving spruce and fir that may eventually reclaim the territory. Fire has an important role in nature. It clears away mature growth, opening areas to the sun-loving species that are food for wildlife. The fire of 1947 increased diversity in the composition and age structure of the park's forests. It even enhanced the scenery. Today, instead of one uniform evergreen forest, we are treated to a brilliant mix of red, yellow, and orange supplied by the new diverse deciduous forests. Bar Harbor, too, was changed by the fire. Most of the permanent residents rebuilt their homes, but many of the grand summer cottages were not replaced. In fact, many of the seasonal families never returned. The estates on Millionaires' Row have been replaced by motels that house the ever-increasing tourist population. But the fire alone cannot be blamed for ending the island’s once-grand "cottage era." The opulent lifestyle had already been suffering from the effects of the newly invented income tax and the Depression. The destructive flames merely provided a final blow. The fire on Mount Desert Island was publicized in headlines in newspapers around the world because the island was a renowned summer retreat for the wealthy. But actually, the fall of 1947 was a dry one throughout the state, and many serious fires occurred. State-wide, more than 200,000 acres, 851 permanent homes, and 397 seasonal cottages were destroyed in "the year Maine burned." |

Last updated: September 1, 2020