Hendricks Family collection, NPS

Its two diesel engines began coughing; the winchman moved the dredge out . . . and the bucket line started to revolve and bite into the gravel. It was a great moment to hear. ---Ernest Patty on the first day of operation of Coal Creek dredge

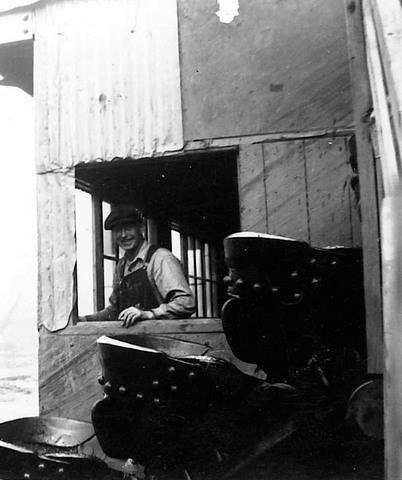

The year was 1936. Gold Placers, Inc. had recently imported an enormous dredge to extract gold on an industrial scale from a Yukon River tributary called Coal Creek. The dredge had traveled north from San Francisco by steamboat, rail, and barge before it was reassembled at Coal Creek. It was designed to eat 3,000 cubic yards of gravel from the drainage each day, leaving behind mounds of discarded rock. Once the dredge was in place, company manager Ernest Patty needed a skilled winchman to work the machine's elaborate system of winches, bucket lines, and conveyor belts. Patty hired a Seattle man named Alvin Hendricks, who was already in Alaska working on a different gold dredge about seventy-five miles to the south of Coal Creek. Alvin, his wife Mildred, and their son Alvin, Jr. moved into a log cabin near the new dredge -- in what is now the heart of Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. The dredge coughed to life and continued processing gravel for the next four decades.

Hendricks Family Collection, NPS For Alvin's wife and son, life revolved around the camp, a collection of frame buildings including a mess hall, bunkhouses for the workers, machine shops, and an assaying office where the placer gold was melted and poured into bricks. In addition to her family roles, Mildred worked hard as camp cook. Al, Jr. was six when he arrived at Coal Creek, and the place offered plenty of youthful adventure. In summer he swam in ponds, played with the Patty's son Stanton, and visited the homestead of a local miner whose gardens were a marvel of northern horticulture. In winter he skied, snowshoed, and checked his trapline with a dog team of three or four led by the family's pet dog Taku.

NPS photo by Chris Allan The Hendricks family returned to Seattle in 1941, and over seven decades later, Al Hendricks, Jr. began to wonder if he might return to Coal Creek to visit his childhood home. When, in 2011, Al's son Manny contacted the Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, and Interpretive Ranger Pat Sanders invited the entire family to visit. After flying by small plane to Eagle, Alaska, Al, Jr., Manny, and Al Jr.'s wife Narci boated down the Yukon to the historic Slaven's Roadhouse near the mouth of Coal Creek. From there, they followed a gravel trail up to the gold dredge and on to the Coal Creek camp. Al Hendricks, Jr. reminisced about his boyhood adventures and cherished the opportunity to share this chapter of his past with his family. He expressed gratitude that the National Park Service had preserved this part of the region's mining history.

Hendricks Family Collection, NPS Memories and photographs

Al Hendricks, Jr. brought with him copies of 25 letters written by his mother to family in Seattle, and over 100 photographs taken by his father and fellow dredge employees. The letters provide an intimate portrait of life at Coal Creek for a frontier family, and the photos share a wealth of historical information about dredge operations and everyday life in a gold mining camp. The photographs illustrate the technology needed to wrest gold from gravel, including workers driving steampoints into the ground to thaw the permafrost, and the construction of a reservoir to capture creek water and gravity-feed it into miles of steel pipe for hydraulicking (using water to blast away soil and gravel layers). The photos document company employees working during the dredge's early years of operation, and scenes of workers and their families at leisure -- celebrating the 4th of July, getting haircuts, and relaxing in their homes. They capture people swinging on a cable over the flooded Coal Creek in spring, and a young Al, Jr. helping to cut firewood and posing behind his dogsled. According to Al, Jr., "Life was a joy at Coal Creek." The photographs capture a small measure of that joy

Part of the long history in Yukon-Charley Rivers

One of the principal reasons that Congress created Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve was to protect and interpret the history of the Klondike Gold Rush, which spilled into Alaska along the Yukon River corridor and led to decades of gold mining across the Last Frontier. Coal Creek, where Al Hendricks worked -- and where Al Hendricks, Jr. and family recently returned to share memories -- is an important piece of that history. Even today, cabins, roadhouses, gold dredges, mining camps, and mining machines large and small can be found in the preserve. They serve as reminders of that dramatic age when people from all walks of life and from around the world raced northward seeking wealth and adventure. |

Last updated: July 28, 2020