Library of Congress Public spirited citizens in Eagle procured the abandonment of two squatters' lots favorably situated on the public land . . . There being no architect in the country the judge and other officials after much talk and more wasted paper, drew and agreed upon plans and specifications. —James Wickersham, Old Yukon (1938) Frontier outposts and mining camps have a reputation for lawlessness and turmoil, and both the Canadian Klondike and Alaskan boomtowns like Eagle City and Circle City had their share. However, even during the pioneer days some measure of law existed to curb crime and anti-social behavior. The informal Miners' Code allowed a delegation of miners to mete out punishments to wrong-doers. Typically these included fines for minor infractions, banishment for theft, and hanging for murder. Before long, however, a new form of law and order arrived in the person of Judge James A. Wickersham.

Alaska State Library, Wickersham Site Photographs Frontier justice As increasing numbers of prospectors arrived in the Yukon River basin in the 1880s and 1890s, they were forced to settle disputes like theft and claim jumping (usurping another man's gold claim) among themselves. The Canadians had not yet established a presence in this corner of their vast northern territories and the only civil government for Alaska was hundreds of miles away in Sitka. In 1893, in the mining camp of Fortymile, miners formed the Yukon Order of Pioneers, a fraternal organization that tried to enforce moral behavior (the order's motto was "Do unto others as you would be done by"). In addition, miners with a complaint could call a meeting that served as an improvised court. In 1894 the Canadian policeman Charles Constantine described the result of one such meeting:

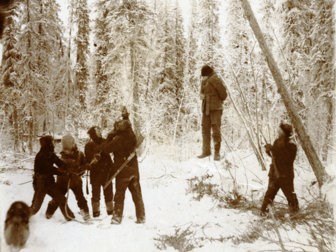

Wickersham's court After the excitement of the gold rush, the United States divided Alaska into three judicial districts and President McKinley selected James Wickersham as judge for the Third District to be headquartered in Eagle on the banks of the Yukon River near the border with Canada. In July 1900 Wickersham arrived with his wife Debbie and son Howard and immediately began levying taxes on businesses in Eagle and the Yukon River towns of Circle and Rampart to build a courthouse and jail. The annual fee for a saloon license was $1000, and for the stores it was a fixed percentage of annual sales. At the time Eagle had just under 400 residents, but it had five saloons and three mercantile establishments which did much of their business with passing steamboats. By May 1901 the construction was done, and young Howard Wickersham raised the stars and stripes over the country's northernmost courthouse.

Anchorage Museum, Claude Hobart Collection. Life and law in Eagle Judge Wickersham rented a small cabin for his family in Eagle and began the daunting task of bringing the law to a district that covered half of Alaska from the Aleutian Island to the Arctic Ocean. It took time for the miners to give up their independent ways regarding the mechanisms of justice, but with the courthouse and Ft. Egbert, the U.S. Army post constructed next to Eagle two years earlier, the town had become less of a gold camp and more a bastion of civil government. Before long the judge was also traveling on a mid-winter circuit to hold court in Rampart and Circle. In 1903, accompanied by his wife and son, he also traveled to the Aleutian Islands and then to Nome where he was sent to remove a corrupt judge. That same year many Eagle residents left to investigate a gold strike in the Tanana Valley, and Wickersham recommended that his court be moved to the emerging boomtown of Fairbanks. By 1904, Wickersham left Eagle and four years later he was elected as Alaska's delegate to Congress—this was the beginning of a long and productive political career. Thanks to the Eagle Historical Society, today the courthouse in Eagle appears largely unchanged since Judge Wickersham's day and serves as a site for historical tours and museum collections. |

Last updated: April 14, 2015