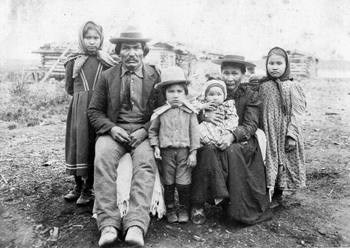

Alaska State Library, Wickersham State Historic Site Collection

Bearded and roughly dressed miners from the creeks, gamblers, actresses, prospectors, preachers, merchants, prostitutes, dog-mushers, hunters, dance-hall fairies, and dogs–a frontier gathering from every land, drawn together by the lure of a mining camp stampede.

—Judge James Wickersham Old Yukon (1938)

For many years before the Klondike-Alaska Gold Rush a handful of prospectors used the Yukon River as a highway on their restless search for gold. In 1893 eighty men left their gold mines on the Fortymile River in Canada when they heard news of a gold discovery at Birch Creek on the American side of the border. In the spring they staked claims and started mining on tributaries they called Mastodon, Hog’em, Miller, Greenhorn, and Independence. The riverside metropolis that sprang up to supply the miners became known as Circle City (for its proximity to the Arctic Circle) and gained a reputation as “the largest log-cabin city in the world.”

University of Washington, Asahel Curtis Collection The men who rushed to the Birch Creek area were grubstaked (supplied with food and supplies) by long-time Yukon River trader and Alaska Commercial Company agent Leroy “Jack” McQuesten. As soon as McQuesten realized the area’s potential he began building a two-story log store and a warehouse. However, he would not long enjoy a monopoly on Circle City business. John Healy, another veteran Alaska trader, moved in with backing from the Chicago millionaires Jack and Michael Cudahy and Portus Weare. Together they formed the North American Transportation and Trading Company with headquarters on the Circle City riverfront.

Before long the population rose to 700, including a group of Athabascan Indians who settled on the edge of town. Steamboats stopped at the town regularly, and each summer miners trekked inland sixty to eighty miles to their claims across swampy land known for the ferocity of its mosquitoes. Arthur Walden came to Circle City in 1896 to become a “dog-puncher,” transporting supplies and mail to the miners by dog sled. He was impressed that for a western mining town, the place was remarkably quiet: “In this town in the summer nothing but pack-trains plodded through the soft muck of the streets; there was no paving; no wagons, no factories, no church bells, not even the laughter of women and children.”

Frontier Justice

Walden also commented on the town’s unusual brand of frontier law and civic society:

From the beginning the town fathers had adopted the so-called Miners’ Code which allowed a delegation of miners to mete out punishments to wrong-doers. Typically these included fines for minor infractions, banishment for theft, and hanging for murder. For this reason Walden could say, “Here life, property, and honor were safe, justice was swift and sure, and punishments were made to fit the case.”

Alaska State Library, Wickersham State Historic Sites Collection By 1897 the town could boast a music hall, two theaters, eight dance halls, and six saloons and the population had risen to over one thousand. The Episcopal Church had opened a hospital, the miners assembled a library, and a government school opened for the children. However, the fortunes of a gold mining town are never certain, and that same year news of gold in the Klondike sent most of the town’s residents scrambling upriver. Over the next two years some miners returned, but most of them rushed off to Nome in 1899. By then the streets fell truly silent and most of Circle City’s four hundred log cabins were abandoned.

Circle Survives

Once the pace of gold stampedes slowed in Alaska, Athabascan families and a few fur trappers and small-scale gold miners helped Circle to survive. Over time the Yukon River shifted and swallowed most of the town’s original log buildings and the residents simply built farther back from the banks. By 1927 the Steese Highway was completed, linking Circle and neighboring Central with Fairbanks, and today many people drive to Circle to put in or take boats out of the Yukon River. Visitors to nearby Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve often use Circle as the end-point of float trips that start upriver at Eagle or beyond.

University of Washington, Evan A. Sather Collection |

Last updated: April 14, 2015