Alaska State Library, James Wickersham State Historic Sites (p277-4-51).

It is strange that men can be found to undertake a task so full of such extraordinary and terrible risks. There is never any difficulty, however. The adventurous life appeals to men of grit and spirit; they say that they prefer it, with all its perils, to a humdrum occupation.

— Seattle Daily Times, June 21, 1903

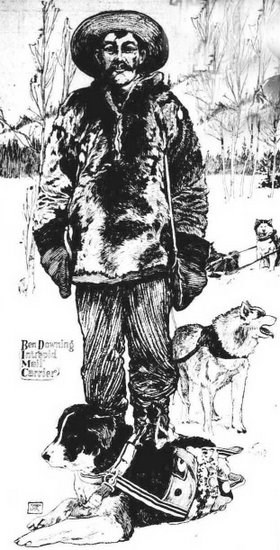

In 1903 the newspaper editor John S. McLain boarded a steamboat in Canada's Dawson City and offered some high praise for one of his fellow passengers: "There is no man in Dawson who has more friends and who is really regarded with more good will by the people of that city than Ben Downing, the veteran mail-carrier of the Yukon." Benjamin S. Downing was born in Maine in 1862 and as a young man tried "bronco-busting and cow-punching" in Arizona before he turned north to join the Klondike stampede. Like so many Far North gold-seekers, he failed to secure paying gold claims and soon turned to other work.

National Postal Museum In 1897 Downing landed a U.S. government-issued contract to deliver mail in the winter from Dawson 600 miles down the frozen Yukon to the mouth of the Tanana River. To make the run, he used specially designed cargo sleds and teams of between eight and ten sled dogs. Along the route Downing took advantage of roadhouses, but he also built his own cabins where roadhouses were not available so that each evening he could make a fire and cook a warm supper for himself and his dogs. Downing and his fellow mail-carriers, a rare breed in a thinly populated region, took their duties very seriously and seemed to enjoy the freedom that the job allowed. Being a mail-carrier was difficult even when conditions were ideal and more often than not carriers faced unpredictable ice conditions, deep snow, and frigid temperatures. As one reporter explained, carriers wore snowshoes and ran ahead of their dogs to break the trail:

Building a business

By 1902 Downing had developed a lucrative business delivering mail, freight, and passengers for the months when Yukon River steamboats were blocked by ice. Most of his passengers took the Eagle & Dawson Stage Line, a horse-drawn sleigh that traveled on a path he and his men cleared along the river each year to cross the international boundary between the two frontier communities. To make the weekly, long-distance mail runs, Downing employed 15 other carriers and used 152 dogs, 48 sleds and toboggans, and 252 sets of dog harnesses. He also imported 52 tons of supplies each year to feed both the men and dogs. Although he could have spent his profits on a life of luxury in Dawson, Downing continued his rounds, sledding as much as 40 miles in a day in all weather and in temperatures that routinely dropped far below zero.

Seattle Daily Times Not only was the Yukon River route considered by many "the world's loneliest mail route," it was also probably the most dangerous. On one occasion, when Downing was heading east from Charley River—in what is today Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve—he suddenly felt his sled being pulled into a hole in the ice. He called to his dog team to climb out of the water, but by the time they scrambled free Downing was drenched from head to foot. He was still several miles from the next roadhouse, and within seconds his clothing froze solid. By the time he reached warmth and shelter, Downing's face was frostbitten and his feet were badly frozen. Unwilling to delay his mail delivery, Downing bound his blistered and swollen feet and refused the urgent appeal of the keeper of the roadhouse to remain. Instead he pressed on to Dawson where, it was said, as he hobbled into the post office his footsteps were marked with blood. Later when he was taken to the hospital, the doctors considered amputating his feet, but Downing tucked a pistol under his pillow and warned them, "If I wake up and find you fellows have cut them off I am going to shoot the man that did it." In the end, he lost four toes but kept his feet. As his friend the newspaper editor put it,

|

Last updated: April 14, 2015