University of Oregon Digital Collections. On my part, I was wild with eagerness to get to a telegraph office and send the news to the world of our success in conquering the Northwest Passage. —Roald Amundsen, My Life as an Explorer (1927)

In the community of Eagle on the banks of the Yukon River visitors often stumble upon a small park and a gleaming metallic monument dedicated to the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. It is not immediately obvious why the first man to sail through the Northwest Passage would be so honored 500 miles from the Arctic Coast, but the reason soon becomes clear: he traveled to Eagle because he needed a telegraph station. As far back as the Middle Ages, European explorers yearned to discover a sea route across North America that would deliver them easily to rich Asian markets. However, the quest for this "northwest passage" remained a dream beyond reach until Amundsen and his crew sailed over the top of the continent in 1905. The reason he needed the telegraph station was to announce this achievement to world.

The explorer's life Born in Borge, Norway in 1872, Amundsen dreamed of becoming a polar explorer even as a small boy. He devoured all the literature he could about the poles and devoted much time to training and strengthening his physique to ready himself for hazardous adventures. At the urging of his parents he studied medicine, but when he was 21 years old both of his parents died and the young man abandoned this career to pursue his dream. He first traveled north as a sailor on an Arctic sealing vessel and then south as first mate on an expedition to investigate the coast of Antarctica. After listening to many scientists debating whether the magnetic poles were fixed or if they moved over time, he had an idea. If he could discover this secret of the North Pole, it would provide a scientific justification (and funding opportunities) for his real goal: sailing through the Northwest Passage in Canada's Arctic Archipelago.

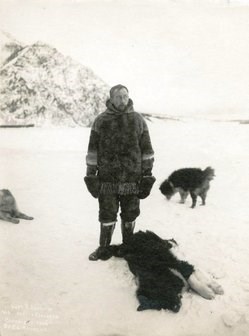

Library of Congress. Life at high latitudes In 1900 Amundsen bought a 72-foot wooden herring boat that he christened the Gjoa. He also selected a six-man crew, men who would become like family in one of the world's most isolated places. On June 15, 1903, the Gjoa was ready to set sail, piled high with provisions for five years of travel and many boxes of scientific equipment. After reaching a protected harbor they called Gjoa Haven in the heart of the archipelago, Amundsen and his men settled down to begin their studies of the magnetic North Pole. Before long a band of Nitsilik Eskimo people arrived and began living alongside the Norwegians. The Eskimos taught their new neighbors how to dress in skins, build houses, and hunt on the ice. Two years later, on June 1, 1905, the Amundsen party continued its journey, this time through the last uncharted waterways that made up the Northwest Passage. The Gjoa groped its way through fog into a shallow, island-studded bottleneck called Simpson Strait with help from Eskimo men in kayaks. The currents were unpredictable and floating ice made the journey exceedingly dangerous. In My Life as an Explorer (1927), Amundsen would later write: Day after day, for three weeks—sounding our depth with the lead, trying here, there, and everywhere to nose into a channel that would carry us clear through to the known waters to the west. Once, in Simpson Strait, we had just an inch of water to spare beneath our keel! An overland journey After threading their way through the maze of islands, the explorers emerged victorious, but they were still far from home. By mid-August their path was once again blocked by sea ice and they settled in for another long Arctic winter near Herschel Island off the north coast of Canada's Yukon territory. American whaling ships were also frozen in nearby, and when the ice was thick enough, the crews began visiting each other. Desperate to notify newspapers of his historic feat, Amundsen formed an alliance of convenience with Captain William Mogg, whose ship had been crushed by the ice. The captain needed to return to San Francisco for a new ship, and the two men hired an Eskimo couple, Jimmy and Kappa, as guides to take them south. With two dog sleds the group set off for the Yukon River 300 miles away.

Library of Congress Link to the world After a month of hard travel, they arrived at Fort Yukon, a village at the northernmost bend in the river. After saying goodbye to their guides, Amundsen and Mogg started out again for the town of Eagle another 200 miles upriver near the U.S.-Canada border. When Amundsen finally stumbled into Eagle he had no money to pay for a telegram and he looked like just another discouraged prospector. But soon the locals realized they had a celebrity in their midst and offered to send his now-famous telegram. However, extreme cold led to delays and frustration: I wrote out about a thousand words which were at once put on the wire. By an odd freak of circumstance, they had no sooner been sent than the cold somewhere on the line broke the wires, and it was not until a week later that they were repaired and I received confirmation that my telegram had reached the outer world. Amundsen would remain in Eagle for two months, resting and reading messages of congratulations wired in from around the world. He was a guest of Alaska Commercial Company agent Frank Smith and participated in the town's winter social functions. In early February 1906 he left Eagle and followed his previous route back to the Gjoa, and five months later the ship and its crew reached Nome to become the first expedition ever to travel from the Atlantic to the Pacific via the Arctic. In the coming years Amundsen joined the race to reach both the North Pole and the South Pole and went on to become one of the most famous explorers of all time. Today Amundsen's 1000-mile detour to reach a telegraph station on the Yukon River has become part of the history of Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve. |

Last updated: April 14, 2015