Frank Slaven Collection

In placer mining in the Far North one of the greatest difficulties encountered is the permanently frozen condition of the ground.

In 1898 when thousands of eager gold-seekers rushed to Alaska and the Klondike, they encountered an obstacle that many did not anticipate: permafrost. Unlike at southern latitudes, the ground in the Far North was frozen all year round, locking the gold in an icy embrace. The earliest arrivals in northern gold fields had no choice but to build wood fires to melt the rock-hard combination of soil, gravel, and ice, but the work was painstakingly slow. The process of drift mining involves digging vertical shafts down to bedrock and then horizontal tunnels along the gold-rich layer called a paystreak. And, the nightly fires the drift miners set would only thaw about twelve inches of gravel and the tunnels quickly filled with smoke and carbon monoxide.

The Klondike-Alaska Gold Rush inspired much innovation, particularly in the field of thawing. An inventor named Greenleaf W. Pichard tried and failed to use an electric-powered furnace to melt frozen ground; others pumped hot water into and out of their mine shafts; and it was an accident in 1898 that led to the widespread use of steam in the thawing process. A Dawson miner named Clarence Berry was using a steam-powered hoist to drag logs up a hill to his mining claim when he noticed that steam spouting from an exhaust hose had melted a hole in a pile of frozen gravel. Further experimentation led to the invention of the steam point, a steel pipe used to deliver steam deep into the frozen earth. By the following year most of the miners in the Klondike goldfields had begun using rubberized hose to connect steam boilers to lengths of steel pipe, which they then hammered into the earth. Early on there was no hydraulic pipe available, leading some to use rifle barrels welded end to end. By fastening a bit to the end and employing multiple points at once, miners would thaw and excavate more gravel than ever before.

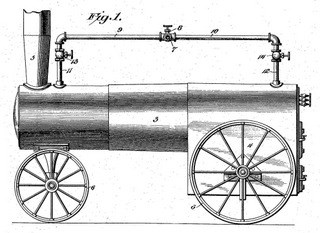

NPS, Hendricks Family Collection In 1935 a company called Gold Placers, Inc. brought industrial-scale placer mining to Coal Creek by buying up the old-timers’ claims and importing an enormous gold dredge capable of processing 3,000 cubic yards of gravel in a day. But, before the dredge could do its work, they had to tend to “ground preparation,” which began with cutting trees, removing stumps, and stripping away the organic layer covering the gravel underneath. Then began the thawing. As general manager Ernest Patty explained, "The gravel was permanently frozen and this permafrost was as resistant to excavation as a mass of reinforced concrete would be." It had to be loosened from its icy grip. As soon as stripping was completed the crew moved on to a new area and the thawing crew moved in to set up their lines of hydraulic pipe and prepare for ‘point’ driving. Each point was a ten-foot length of extra-heavy steel pipe . . . with a chisel bit welded on one end. To begin the thawing they used a “locomotive type” 40-horsepower boiler named for its similarity to those used as train engines. It was over 15 feet long, weighed over 8,000 pounds, and could deliver steam to hundreds of points. However, it also consumed 250 cords of wood that first season, which convinced Patty to try other techniques. From then on they pumped air-temperature water through the same network of points. It was less costly and turned out to be just as effective.

Boilers on the Landscape

Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve was created in part to protect and interpret the history of the Klondike- Alaska Gold Rush, and today visitors can still see the Coal Creek gold dredge and the steam boiler that played a role in the dredge’s first year of operation. In fact, evidence of Coal Creek’s heyday as a mining camp can be found up and down the creek valley. These artifacts serve as an open-air museum, reminding us of the fierce determination and ingenuity of gold miners along this section of the Yukon River corridor.

NPS/Chris Allan |

Last updated: April 14, 2015