The Lyell Fork Tuolumne River with Mount Lyell and the Lyell Glacier in the background. Melt from the Lyell Glacier keeps the river flowing year round.

August 29 marked the 142nd Anniversary of the first recorded ascent of Mount Lyell, Yosemite’s highest peak (13,114 feet). J. B. Tileston made that ascent in 1871. He left his base camp at four in the afternoon the day before he summited. Darkness found him bivouacked high in the mountains where he

…made some tea in a tin cup, and enjoyed the strange and savage scene around me. Immense precipices, great masses of snow, from which rose the black peaks of the summit, the roar of water descending by many channels and cascades over and among the rocks, and occasionally the rattling down of loosened stones, and the novelty of my situation alone in that wild place, made a scene which impressed itself on my mind. Soon the moon, nearly full, rose over a great line of precipices half a mile across a gorge up which I had come, and gave new attractions to the view.

I was up early next morning, toasted some bacon, boiled my tea, and was off at six. I climbed the mountain, and reached the top of the highest pinnacle (‘inaccessible,’ according to the state geological survey), before eight. I came down the mountain, and reached camp before one, pretty tired.

John Boise Tileston

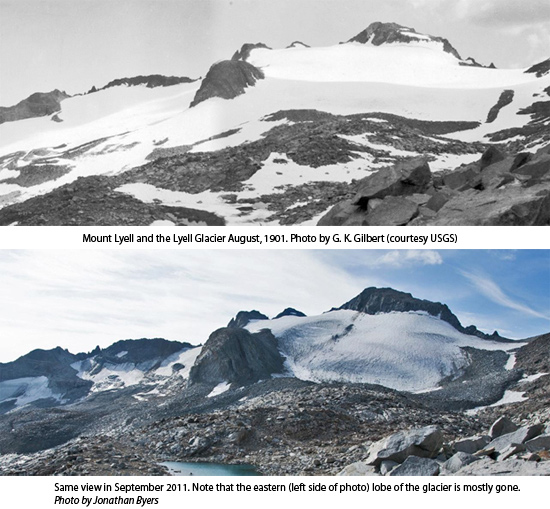

When I first began working in Yosemite back in the late 1960s, one of my goals was to climb to the summit of Mount Lyell and see the Lyell Glacier, Yosemite’s largest and the second largest glacier by area in the Sierra Nevada. What could be more iconic of Yosemite’s ice carved scenery than the park’s largest glacier nestled in the rugged breast of Yosemite’s highest peak? In those days the journey involved walking up the glacier and stepping across a narrow part of the bergschrund, a cavernous break at the top of the ice. From there it was just a few more steps to a rocky plateau that led to the summit. Today, those few steps off the top of the glacier have become well over a hundred feet of rock climbing; more than half of the Lyell Glacier has melted away due to climate warming. Yosemite’s only other glacier, the McClure, has also melted back considerably.

In the mid-nineteenth century, people did not understand that glaciers once covered mountains and filled canyons of the Sierra, including Yosemite Valley. John Muir developed an idea that flowing ice had sculpted Yosemite Valley and the high Sierra. To help him prove this, he decided to measure glacier movement. In 1872 he and his friend Galen Clark carefully documented movement of the McClure Glacier. They used two stationary locations in the rocks on either side of the ice to create a baseline. Muir and Clark drove stakes into the ice along that line. Returning 47 days later, they sighted along the baseline and found that the ice had carried the stakes downstream at the rate of about an inch a day. More than a hundred years later that groundbreaking experiment would be repeated.

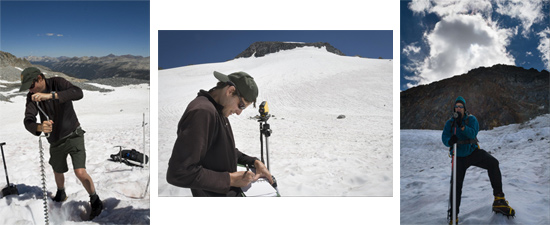

![]() Photographs taken over the years reveal a drastic reduction in the size of Yosemite’s remaining glaciers, especially in the last few decades. This documented change prompted park geologist Greg Stock to team up with Robert Anderson of the University of Colorado and repeat Muir’s measurements on the McClure Glacier exactly 140 years later to the day. They did the same for the Lyell Glacier.

Photographs taken over the years reveal a drastic reduction in the size of Yosemite’s remaining glaciers, especially in the last few decades. This documented change prompted park geologist Greg Stock to team up with Robert Anderson of the University of Colorado and repeat Muir’s measurements on the McClure Glacier exactly 140 years later to the day. They did the same for the Lyell Glacier.

Stock and Anderson learned that the McClure Glacier was flowing at the rate of about one inch per day–the same as Muir’s measurements had detected. This seems odd because the size of the glacier is so much smaller than it was in Muir’s time. One possible explanation is that the glacier is melting so fast that the additional runoff lubricates the bottom of the ice allowing it to slide more easily across the rock.

They made the same measurements on the Lyell Glacier and after four years the stakes had remained stationary. The inevitable conclusion was that Yosemite’s largest glacier has stagnated. The ice continues to melt and by Yosemite National Park’s second centennial it may be completely gone. For hundreds of years, snow and ice melt from the foot of these two glaciers has fed the Tuolumne River and kept it flowing even in late summer and fall when other streams have dried.

Over the years I’ve made several attempts to climb Mount Lyell and its glacier but each time lightning storms in summer or avalanche danger in winter prevented me from completing the ascent. Although this may be disappointing to me, I am truly saddened by the fact that the last of our glaciers, these icy icons of wildness, may disappear within the lifetimes of my children and with them a source of late summer water for streamside life along the Tuolumne River.

For another perspective of Lyell Glacier, read a fellow ranger's blog post "Ode to the Lyell Glacier."