[Read parts one and two of this story.]

Leaving the yearlings at the den site was hard; after all the effort everyone had put in to get them to that point. Biologists watched their GPS data closely, and after about a month of hibernation in their human-made den, the bears began to explore their surroundings. Trail camera photos showed them playing with each other as they explored their new home, with the larger male expressing dominance and playfully chasing the others around their den site. After another month, the three intrepid young bears began to disperse, venturing to find their own home ranges and stake a claim in Yosemite’s expansive wilderness.

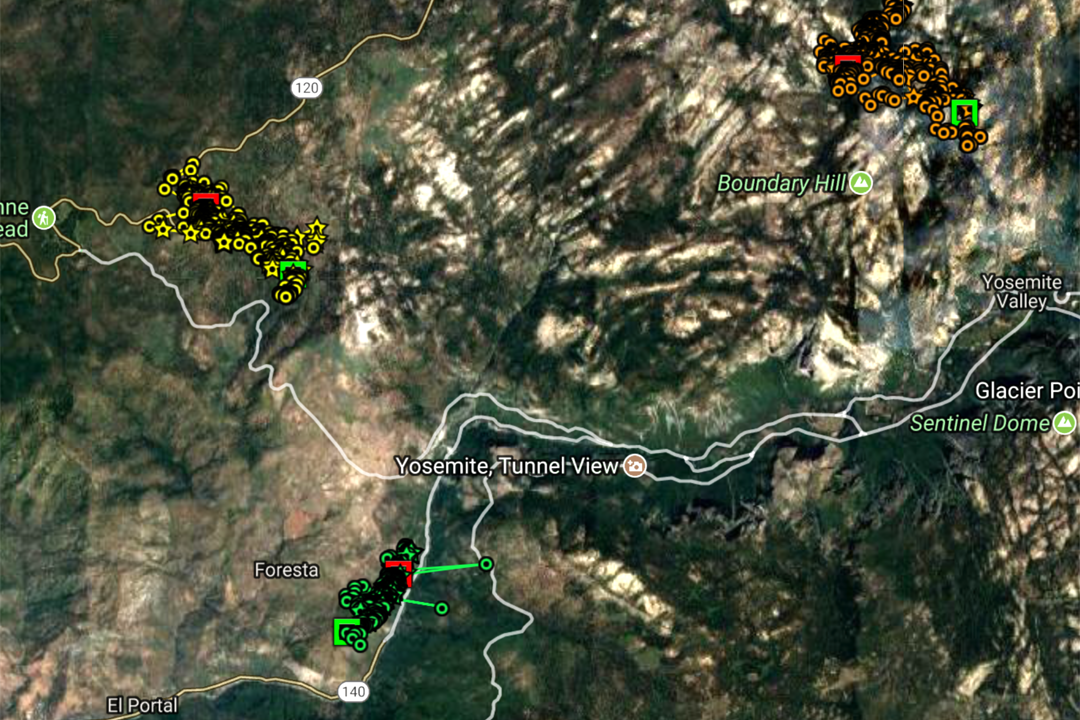

The smaller of two males settled in an area between Foresta and the El Portal Road, high on a ridge. He kept to himself, and moved around a lot, likely searching for various food sources, but he never interacted with people on trails or in developed areas. This bear’s collar stopped communicating GPS points to satellites in late spring. Without location data from the collar, biologists could now only track this bear using radio telemetry (which is limited by geography and distance: to pick up the collar’s signal via radio waves, biologists must be within ‘line of sight’ of the collar, and close enough to hear it using a radio receiver). It took the rest of the fall and summer before the collar was found, which required dedicated biologists bushwhacking several hours through manzanita on rough terrain. Unfortunately, when they found the collar, they also discovered remnants of fur and the bear’s ear tag which led them to believe the bear had died earlier in the year from natural causes. While the collar failed to transmit GPS locations after late April, data recovered from the collar indicates that this bear died in late June 2017. This bear was too far from development to assume that the death was related to humans, and it is common for wild animals to die naturally within their first few years of life (generally, about a quarter of black bear cubs are expected to die during their first year, and a third die within the next two years).

The small female sibling settled in an area near Yosemite Creek, deep in the wilderness. Her collar transmitted until the day it automatically dropped off in July. Our last glimpse of her was along a trail, far from roads and people; she looked healthy and acted skittish around humans. She may end up living 30 years or more in Yosemite’s wilderness, raising cubs of her own, foraging on wild berries and insect larvae, existing as an integral part of the glorious wildness she was born into.

The third cub, the larger male, had a more elaborate (and cautionary) story. For quite a while, this bear found good natural forage around a closed seasonal campground in the park. However, once the campground opened to visitors in June, the bear began foraging opportunistically in the same area on human food and garbage that was either left out or improperly stored. Very quickly, staff from across the park pulled together and began an around the clock effort to protect this tenacious little bear, including continuous education of campers, increased trash pick-ups, and long nights of chasing the bear out of the campground in hopes of convincing him that people were scary, and not worth the opportunistic food rewards. However, when all of these efforts were clearly not working to change the bear’s behavior, biologists decided to try relocating the bear. While bear relocations are generally unsuccessful, they sometimes work on young animals that are still establishing home ranges. So, this bear was relocated a short distance away in suitable habitat, where he immediately went back to foraging naturally and avoiding people.

A bear’s life, however; revolves around a continuous search for food; and since food availability changes seasonally at different elevations, bears must move to follow that available food. Heading into fall, wildlife management staff began receiving reports of this bear seen passing through a residential area over 15 miles (as the crow flies) and roughly 4,000 feet lower in elevation from where he spent his summer. By November, this bear had dropped down into the park’s administrative site, El Portal. There, the bear was gorging on natural food, including wild grapes and acorns. The only problem was that all this great natural food was, again, close to people; in a residential area and next to a busy highway. Bears that become comfortable close to people around homes worry wildlife managers, because it only takes one human mistake, like leaving a window open or garbage out, for a bear to get a large amount of food and associate this reward with people and houses. If that happens, it can immediately and dramatically alter the bear’s behavior as it shifts to actively seeking out human food or breaking into buildings instead of continuing to forage naturally. Knowing this, wildlife management staff again dedicated their time to scaring the bear out of developed areas and increased efforts to alert the community to be vigilant about food storage.

Days passed with community members and park staff pulling together in hopes of keeping this bear safe until the season turned and winter arrived, when food would become scare and this bear would hopefully find a den for the winter away from the neighborhood. Unfortunately this time, all of the hard work and joint efforts to give this bear a long, wild life eventually failed. On October 30, wildlife management staff found this bear, orphaned after its mother was hit and killed by a car, also dead in the road. It was a somber day. We all know that speeding kills bears—or more accurately, driving kills bears–—but it was hard to stomach that this would be the fate of a bear who we thought we saved from the same tragedy two years earlier.

This project, along with the data we have collected over years of careful monitoring of bear vs. vehicle collisions in Yosemite, has hit home with resource managers and many others in Yosemite. All it takes is having to drag one dead bear off of the road in order to realize how impactful our driving can be to other species. Wildlife-vehicle collisions are one of the largest human-wildlife conflicts we face today, and we all need to do more to change these statistics. This is an issue the National Park Service has worked hard on with limited successes in past years. With as many as 39 reported bears hit by vehicles in the park in a single year, we are dedicated to use this new momentum to refocus our energy on creating new partnerships, new tactics, and new solutions for this difficult problem.