The lodgepole pine is one such tree. Lodgepole are found in many western states, from Colorado to California. They are hearty, equipped to survive in a variety of conditions, and perhaps one of the more well-known high mountain trees. It is the only pine in Yosemite whose needles grow in clusters of two. Lodgepole can also be identified by their scaly, grey colored bark. The lodgepole pine forest community is by far the largest vegetation type in Yosemite, covering over 150,000 acres.

Despite its hearty stature, large stands of lodgepole pine can be found bleached of their color and stripped of their bark, in what are known as "ghost forests." Although temporary, some of these trees stand in contrast, surrounded by healthy neighbors, for over 60 years. During the 1950s some 46,000 acres of lodgepole in Yosemite had effectively been defoliated and transformed into a ghost forest. So, how did some of the sturdiest high elevation trees die off in such large numbers?

Believe it or not…a moth is at the root of it all!

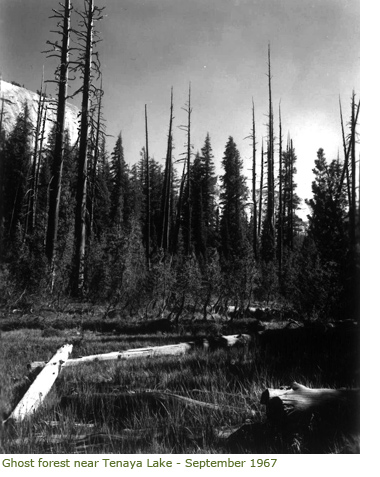

When found in great quantities a tiny moth with a wingspan of about a quarter inch can effectively defoliate acres of lodgepole pine. Native to the Sierra, the needleminer moth was responsible for damaging an estimated 100,000 park acres. Since 1900 there have been several needleminer moth epidemics in Yosemite National Park history: between 1903-1921, 1933-1941, and 1947-1963. The ghost forest of Tenaya Lake once told the story of one of these infestations. Ghost Forest near Tenaya Lake - Sept. 1967

When found in great quantities a tiny moth with a wingspan of about a quarter inch can effectively defoliate acres of lodgepole pine. Native to the Sierra, the needleminer moth was responsible for damaging an estimated 100,000 park acres. Since 1900 there have been several needleminer moth epidemics in Yosemite National Park history: between 1903-1921, 1933-1941, and 1947-1963. The ghost forest of Tenaya Lake once told the story of one of these infestations. Ghost Forest near Tenaya Lake - Sept. 1967 This tiny creature created quite a buzz in Yosemite. The earliest infestation and creation of the ghost forests, consisting of "widow-making," gnarled branches, worried park managers who wanted to provide recreational opportunities around Tuolumne Meadows. The infestation was thought to be negative and multiple agencies sought to exterminate the forest pest. In the beginning they attempted extermination using various techniques but mainly by cutting trees, peeling off limbs and bark, and then burning them. In the 1930s oil was sprayed on lodgepole. In 1949 chemical insecticides were used to manage the population. The first chemical introduced was DDT, but after spraying 20 acres, it was proven ineffective. Eventually other chemicals were found to be more effective, and spraying continued into the 1980s. Just prior to the 1980s there was a movement to control populations in a more ecologically friendly way. Scientists and park managers instead sought to answer the question: How do these tiny creatures manage to create acres of ghostly trees? They began to investigate the life cycle of the needleminer moth. Entomologists and researchers set up a field camp in Tuolumne Meadows to learn about what causes the rise and fall of the epidemic populations. Between 1955 and 1963 the Insect Research Station also known as "Bug Camp" allowed researchers to study and record the amount of eggs, larvae, pupae, and adult needleminer populations. This would help scientists to better understand the life cycle of the needleminer moth;the information gathered proved to be pivotal in helping to understand the Park's population and infestation cycles.

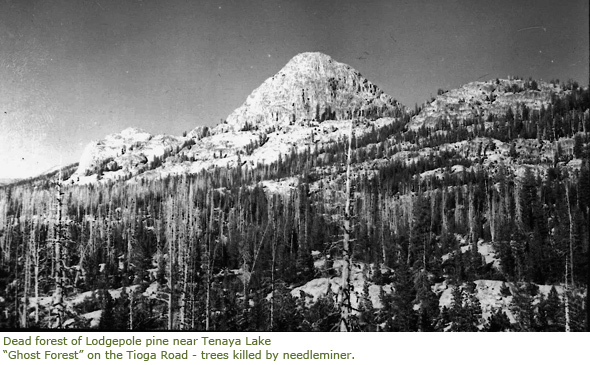

The needleminer moth's life cycle spans two years. Typically the moths emerge, mate, and lay their eggs every odd year between mid-July and mid-August. Incubation lasts a little over a month. When they emerge, the larvae (a worm-like creature), begin "mining" their way into and out of single needles (hence the name). One needleminer larva can effectively "mine out" a minimum of five needles. They will remain in the last needle in order to complete their metamorphosis into an adult moth. Lodgepole, being a survivalist, can withstand a number of defoliations before they begin to die. After a series of defoliations the trees become weakened and more susceptible to the mountain pine beetle. The result produces acres of bleached white, ghostly limbs. Dead forest of Lodgepole near Tenaya Lake - "Ghost Forest" on the Tioga Road - trees killed by needleminer.

Today's practices allow for natural systems to play their role in forest/pest ecology. For me, the series of needleminer events in Yosemite stand as reminders of how even the smallest of things can so greatly affect even the strongest. Despite their unique appearances, the ghost forests were thought of as dangerous, unappealing places to spend time. The park answered the question, "who wants to camp in a ghost forest," by first trying to eradicate infected trees and when that didn't work they moved on to chemical insecticides. All in effort to maintain and provide recreational opportunities for park visitors. But if the infestations are a natural process, ghost forests would be a naturally subsequent result. So, I wonder, what do you think wilderness should look like? What is does it mean to be a "picture perfect" park? And at what lengths should we interfere to create this ideal?