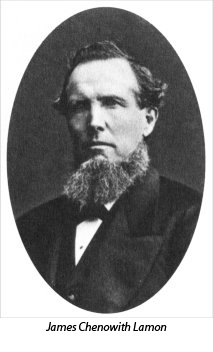

James Chenowith Lamon (pronounced “lemon”), a native of Virginia, came to California during the Gold Rush in 1851. Lured by stories of a great valley he was one of the first few hundred tourists to visit Yosemite in the late 1850s. After deciding to make the Valley his home, Lamon bought the possessory rights of several men in 1859. Yosemite and much of the Sierra Nevada had not been officially surveyed to be offered at auction by the General Land Office. At the time, federal law allowed you to preemptively claim a homestead on public land, which would be honored when the land was surveyed given that you could show a certain number of months of residence and a certain number of improvements. The men that came before Lamon were not living in the Valley and had not improved their claims. Lamon filed his official preemption claim there in 1861.

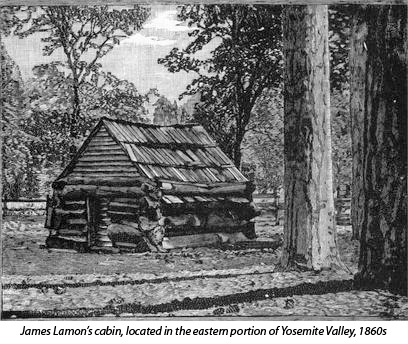

Lamon got busy on his new land and built a small log cabin, the first one in the Yosemite Valley, located in the east end near the present day stables. Several other pioneers still maintained claims in the Valley, but this marked the first real homestead by settlement.

In the winters of 1862-63 and 1863-64, Lamon stayed in Yosemite Valley while all other settlers and pioneers moved down to the foothills. Can you imagine what that was like? No contact or communication with the outside world, having to withstand the weather that winter would bring, hoping that you’ve prepared well enough. What if something happened and you needed help? It must have been unsettling that your closest neighbor was over 30 miles away. It seems Lamon’s friends were nervous too. James Mason Hutchings, an early settler and friend of Lamon, writes about it in his 1888 book, In the Heart of the Sierras:

“…an Indian had been seen in the settlements with a fine gold watch, that, it was surmised, belonged to Mr. Lamon. Fearing that its supposed owner had been murdered, as well as robbed, three friends left Mariposa for the purpose of ascertaining the facts of the case. Upon arrival, to their great joy, they found the man, presumably murdered, busily engaged in preparing his evening meal. Both Mr. Lamon and his watch were proven to be safe. It can readily be conjectured that their congratulations and rejoicings must have been mutual, although viewed from widely different standpoints.”

Lamon demonstrated what the American Indians in the area had known for centuries, living through the winter in Yosemite Valley was possible. This is a fact that Hutchings and other settlers took note of and began making their plans to live year round in the Valley too.

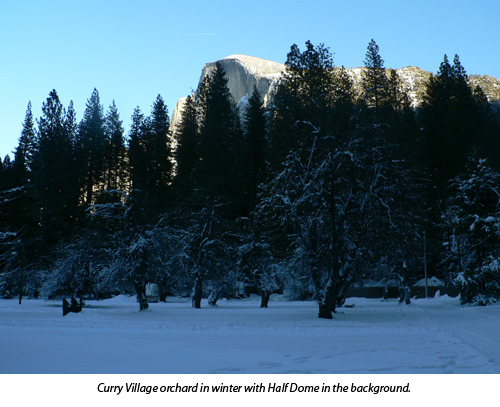

A proficient farmer, Lamon had soon established two orchards and fields for hay, berries, and vegetables. Lamon sold his fruits and vegetables and feed for horses to early tourists and hotel keepers. Many of the fruit trees planted by Lamon still exist in the Valley, producing fruit to this day. The next time you park your car at Curry Village, look up at the historic apple trees around you. All of them were originally tended by Lamon.

In 1864, Lamon suddenly found himself a squatter on permanently public land after the Yosemite Grant was signed on June 30th. This Act of Congress, signed by Abraham Lincoln, protected Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias for all time, giving that land to the State of California to manage. The Board of Commissioners of the Yosemite Grant offered ten year leases to the pioneers that had claims within the boundaries of the Grant. The rates were nominal, often as low as one dollar per year, but Hutchings convinced Lamon and couple other settlers not to sign a lease for the land that they believed was theirs. After a lengthy court battle and much publicity, mostly orchestrated by Hutchings, the State eventually bought out the remaining settlers, including Lamon’s property in 1874 at a cost of $12,000.

Lamon did not get to enjoy this fortune long. Only nine months later, after spending 13 years as a permanent resident of Yosemite Valley, Lamon died of pneumonia on May 22, 1875. $1,500 of his estate went to purchase the large monument that stands in the Yosemite Cemetery where he is buried. The

recently cleaned monument was carved from a piece of granite taken from Yosemite Valley.

James C. Lamon made a life for himself in Yosemite at a special time. By providing food for visitors and horses, he contributed a vital part of the budding tourist industry here. I’m sure nothing tasted better than a fresh apple after the hot and dusty ride to the Valley. As a homesteader in the nation’s first protected public land, Lamon also got to witness the growing pains of the national park idea. And that idea is still growing today, just like Lamon’s apple trees.

James Chenowith Lamon (pronounced “lemon”), a native of Virginia, came to California during the Gold Rush in 1851. Lured by stories of a great valley he was one of the first few hundred tourists to visit Yosemite in the late 1850s. After deciding to make the Valley his home, Lamon bought the possessory rights of several men in 1859. Yosemite and much of the Sierra Nevada had not been officially surveyed to be offered at auction by the General Land Office. At the time, federal law allowed you to preemptively claim a homestead on public land, which would be honored when the land was surveyed given that you could show a certain number of months of residence and a certain number of improvements. The men that came before Lamon were not living in the Valley and had not improved their claims. Lamon filed his official preemption claim there in 1861.

James Chenowith Lamon (pronounced “lemon”), a native of Virginia, came to California during the Gold Rush in 1851. Lured by stories of a great valley he was one of the first few hundred tourists to visit Yosemite in the late 1850s. After deciding to make the Valley his home, Lamon bought the possessory rights of several men in 1859. Yosemite and much of the Sierra Nevada had not been officially surveyed to be offered at auction by the General Land Office. At the time, federal law allowed you to preemptively claim a homestead on public land, which would be honored when the land was surveyed given that you could show a certain number of months of residence and a certain number of improvements. The men that came before Lamon were not living in the Valley and had not improved their claims. Lamon filed his official preemption claim there in 1861.