The subject's Half Dome story begins a week earlier, when he bought new hiking boots at an outdoor recreation store. The salesperson advised the subject not to wear his new boots on his upcoming Half Dome hike, since new boots that haven't been broken in on shorter hikes often cause hot spots, blisters, and soreness on a long, strenuous hike like the Half Dome hike. Even so, the subject chose to wear his new boots.

The subject and his group started hiking at 6:30 am on Wednesday. The subject reported that he did not eat breakfast and did not pack any food for his hike; he received granola bars and snacks from other hikers along the trail. The subject brought drinking water, which he consumed during the day; when he ran out of water, his daughter and her friend shared their remaining water with him. Early on during the hike to Half Dome, somewhere near the top of Vernal Fall (1.5 miles and 1,000 feet in elevation above the trailhead) the subject's daughter and her friend suggested that the subject return to the trailhead, explaining to him that he already appeared tired. The subject insisted that he wanted to continue hiking.

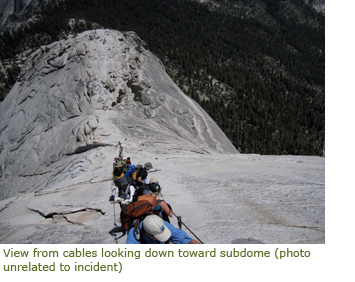

The group of three arrived at the base of the Half Dome cables in the afternoon, around 2:30 pm. The subject's daughter immediately felt anxious as she started up the cables; she panicked, stopped her ascent, and descended back down the cables with her friend. They implored the subject not to proceed up the cables, but he continued his ascent. The subject's daughter and her friend then hiked down the sub dome to the Half Dome permit checkpoint, where they waited for the subject. At approximately 4:30 pm, a guided hiking group arrived at the checkpoint after descending the cables and the sub dome, and the subject's daughter asked the group if they had seen her father. The group recalled seeing him approaching the top of the cable route around 3:30 pm, appearing exhausted. The hiking group contacted the Yosemite Emergency Communications Center (ECC), conveying concern on behalf of the subject's daughter (whose cell phone didn't have reception at that location). The daughter (via the hiking group) requested immediate assistance for her father. After speaking by phone with a ranger assigned to the case, members of the hiking group went back up the sub dome in an attempt to locate the subject. They called back 20 minutes later, reporting that they had found the subject and were accompanying him back down to his daughter and her friend.

The group of three arrived at the base of the Half Dome cables in the afternoon, around 2:30 pm. The subject's daughter immediately felt anxious as she started up the cables; she panicked, stopped her ascent, and descended back down the cables with her friend. They implored the subject not to proceed up the cables, but he continued his ascent. The subject's daughter and her friend then hiked down the sub dome to the Half Dome permit checkpoint, where they waited for the subject. At approximately 4:30 pm, a guided hiking group arrived at the checkpoint after descending the cables and the sub dome, and the subject's daughter asked the group if they had seen her father. The group recalled seeing him approaching the top of the cable route around 3:30 pm, appearing exhausted. The hiking group contacted the Yosemite Emergency Communications Center (ECC), conveying concern on behalf of the subject's daughter (whose cell phone didn't have reception at that location). The daughter (via the hiking group) requested immediate assistance for her father. After speaking by phone with a ranger assigned to the case, members of the hiking group went back up the sub dome in an attempt to locate the subject. They called back 20 minutes later, reporting that they had found the subject and were accompanying him back down to his daughter and her friend. At approximately 6 pm, the subject's daughter, using her own cell phone, called the ECC, reporting that her group of three had run out of food and water and were stopped at the Half Dome-John Muir Trail junction (about two miles below the summit of Half Dome). A YOSAR responder stationed at the Little Yosemite Valley Ranger Station (3.5 miles below the summit of Half Dome) called the subject's daughter and counseled her to proceed downhill to the ranger station; when the threesome arrived, they were given food and water, and then they resumed their hike downhill.

The subject was exhausted and his feet were in pain, so the group's progress was extremely slow. As darkness fell, with only one small flashlight and no map between the three of them, they became confused about the trail system and which way to go to reach the trailhead. The two YOSAR responders who arrived at their location at 9 pm assisted the subject in hiking out; on the treacherous Vernal Fall steps, one of the two rescuers trailed behind the subject, holding onto his backpack from behind, while the other positioned himself in front of the subject, offering a hand to prevent the subject from pitching forward and falling. The group reached the trailhead at 12:30 am.

In the meantime, a separate rescue effort for another Half Dome hiker was underway. The wife of a 58-year-old male hiker called the Yosemite ECC at approximately 9 pm to report that her husband, who had "no cartilage left in his knees," had successfully hiked up to the top of Half Dome earlier in the day, but the hike back downhill was proving difficult. The hiking party had run out of water but still had food; the subject's wife was advised to have the subject rest and eat, while a ranger set off on the trail to find the subject and assess his condition. Upon arriving at the subject's location, on the switchbacks of the John Muir Trail below Clark Point, it was clear to the ranger that the subject simply could not hike any farther, so he requested a litter team. The litter team carried the subject down to the trailhead; the rescue was complete by approximately 1:15 am.

In the meantime, a separate rescue effort for another Half Dome hiker was underway. The wife of a 58-year-old male hiker called the Yosemite ECC at approximately 9 pm to report that her husband, who had "no cartilage left in his knees," had successfully hiked up to the top of Half Dome earlier in the day, but the hike back downhill was proving difficult. The hiking party had run out of water but still had food; the subject's wife was advised to have the subject rest and eat, while a ranger set off on the trail to find the subject and assess his condition. Upon arriving at the subject's location, on the switchbacks of the John Muir Trail below Clark Point, it was clear to the ranger that the subject simply could not hike any farther, so he requested a litter team. The litter team carried the subject down to the trailhead; the rescue was complete by approximately 1:15 am. Key components for making any given hiking adventure safe and successful are (1) having an adequate fitness level for the chosen hike and (2) knowing the limits of your own physical abilities. In the case of the second rescue, had the subject tried a shorter uphill hike before attempting the Half Dome hike, it is possible he would have discovered that his knees could not handle the stress of hiking back downhill. Half Dome hikers routinely underestimate the level of difficulty of the hike; from the trailhead at Happy Isles, in Yosemite Valley, to the top of Half Dome, the trail gains 4,800 feet in elevation, and the hike is 14 to 16 miles round trip, depending on which route hikers use. Most hikers take 10 to 12 hours to hike up and back (please note, permits to hike to the top of Half Dome are required seven days a week when the cables are up). Proper preparation is also critical. For a strenuous all-day hike like the Half Dome hike, bringing plenty of drinking water (1 gallon is recommended), food, a headlamp or flashlight for each member of the hiking group, and a detailed map is a must. As the first rescue illustrates, wearing proper footwear helps prevent problems from developing on the Half Dome hike: choose comfortable, well broken-in shoes or boots with good traction and ankle support (tennis shoes are not recommended).