In a world of 3D megaplexes that bring wine and popcorn directly to your seat and the infinite entertainment of digital media, it's difficult to imagine looking at still photographs as an enticing idea for a date. But in the second half of the 19th century, devices like the Sweetheart Stereoscope were a new, exciting, and romantic way for two people to share in the magic of photography. The Sweetheart Stereoscope in the Yosemite Museum collection stands around three feet tall and has a viewer on either side, allowing for two people to gaze into at the same time—hence the 'Sweetheart' name (YOSE 118728). As dated and obscure as the stereoscope may seem compared to our high-def camera phones, this object was once a powerful and mesmerizing instrument for uniting two people.

In a world of 3D megaplexes that bring wine and popcorn directly to your seat and the infinite entertainment of digital media, it's difficult to imagine looking at still photographs as an enticing idea for a date. But in the second half of the 19th century, devices like the Sweetheart Stereoscope were a new, exciting, and romantic way for two people to share in the magic of photography. The Sweetheart Stereoscope in the Yosemite Museum collection stands around three feet tall and has a viewer on either side, allowing for two people to gaze into at the same time—hence the 'Sweetheart' name (YOSE 118728). As dated and obscure as the stereoscope may seem compared to our high-def camera phones, this object was once a powerful and mesmerizing instrument for uniting two people.

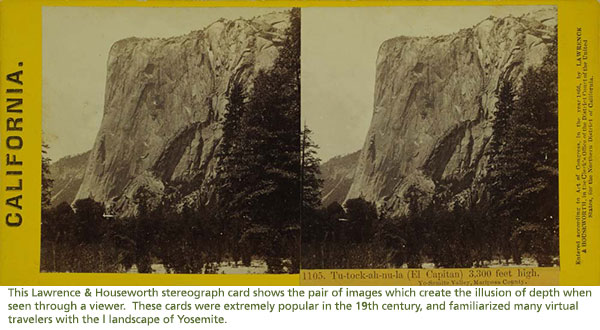

The stereoscope was invented on the principle that when two photographs—one intended for the left eye and one for the right—were viewed at once, the brain would fuse them into one three-dimensional image. The idea was first put into product by Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1838 in the form of two mirrors at 45 degree angles to the viewer's eyes. The mirrors reflected a drawing that was off to each side. With the invention of the first practical photographic process only a year later, Wheatstone's idea was soon adapted to photographs: the mirrors were replaced by two differently-angled photographs of the same view to again make one three-dimensional image. Queen Victoria was known to have been enthralled with these devices at the Great Exhibition of 1851 and an industry was born overnight. Hand-held stereoscopic devices became wildly popular. The demand for 3D images was enormous from all walks of Victorian life, from children to philosophers and scientists.

Truly, the stereoscope began as a scientific exploration of human vision. Wheatstone's first findings are published in his paper titled, "Contributions to the Physiology of Vision." The Victorian age was fascinated by the bounds, mechanisms, and implications of human sensory organs. The machinery of vision was prodded, mimicked, modeled, and most prominently, exalted. The invention of the stereoscope, and photography along with it, were testaments to the conception that the human eye was the ideal optical instrument and a true witness to nature. The devices were manifestations of the belief that human double-vision was perfect vision. The stereoscope and the camera were largely regarded as substitutes for the innate fidelity of the eyes, though there was debate over whether these instruments could, in fact, surpass human capabilities. There was enormous interest, both scientifically and philosophically, in the merits and theological implications of perfection in human physiology.

At the same time, photography was a miracle. A machine froze the living world and transposed it upon a surface in vivid detail. Nature was revealed, uninhibited. Photography made the world strikingly present with rich depth and solidity. Using photographic images, the stereoscope provided clarity and fidelity in three-dimensions; for the first time, the viewer could believably see a scene mind-bendingly similar to nature's splendor.

Understandably, scientists and philosophers were not the only ones captivated by the stereoscope. Despite its pivotal role in academic studies of physiology, neurology, and even theology, the stereoscope is most widely regarded as a ubiquitous Victorian amusement. The Victorian era was one that heralded "philosophical toys," entertainments that were fun but that also illustrated some scientific concept. The stereoscope fit into this category alongside the kaleidoscope and zoetrope;instruments discussed in high-brow circles that could also just as easily be enjoyed by children. By the 1870s, stereo viewing was an immensely popular pastime. Across the nation, seemingly every parlor housed a stereoscope and stereoscopic images to go in it, including many of the most famous views of Yosemite National Park.

People were amazed by the capabilities of these devices. The Sweetheart Stereoscope was designed to add a nudge of intimacy to the already powerful experience of sharing the awe of a stereographic photograph. In a way, when two lovers gaze into the viewer, it is like they are sharing a kiss or close embrace. Standing close and facing one another, their eyes don't see the face of their partner, but perhaps they still see a bit of magic.