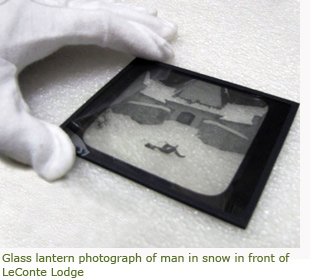

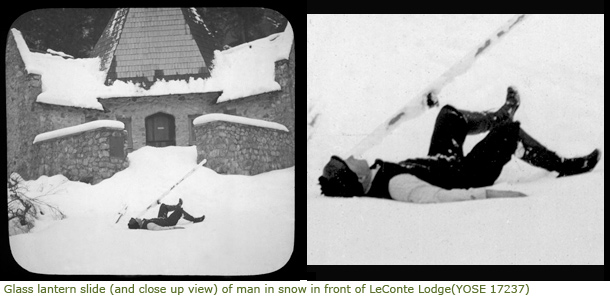

On a small piece of glass, no bigger than 3'x3', a man floats midair. He is lying down, face to the sky, suspended in nothingness, drifting in the clear elixir of frozen glass. Yet when I place the slide down on a white piece of paper, he becomes surrounded by snow. As he lays in the soft cold whiteness you can almost feel the snowflakes hit his nose with a frigid prick and slowly melt into his warm pink skin. His wool gloves are scratchy and there is that surreal glow from the light reflecting off the snow all around him as he stares into the bright grey sky that keeps dusting the earth with these tiny cold specks.

On a small piece of glass, no bigger than 3'x3', a man floats midair. He is lying down, face to the sky, suspended in nothingness, drifting in the clear elixir of frozen glass. Yet when I place the slide down on a white piece of paper, he becomes surrounded by snow. As he lays in the soft cold whiteness you can almost feel the snowflakes hit his nose with a frigid prick and slowly melt into his warm pink skin. His wool gloves are scratchy and there is that surreal glow from the light reflecting off the snow all around him as he stares into the bright grey sky that keeps dusting the earth with these tiny cold specks.

This is the magic of glass lantern photographs. Today, hundreds sit stacked in the Yosemite Museum Collections Room just waiting for someone to have a moment like this. It is a moment when you come into contact with a piece of art and a moment in time, when you feel like you are really living in it in the present, when you feel jolted awake and in tune with all of your senses at once. Of course, this slide (YOSE 17237) was not meant to be seen against white paper and especially not against plain air, leaving the figure floating in the abyss of whatever wall or shelf is nearest and visible through it. It was made to be projected onto a large surface to be shared with many people. Glass lantern photographs revolutionized photography in that way; taking a previously intimate and personal experience with a print and expanding it into something large and communal that large groups could enjoy together. And yet there is still magic in the physical slide, in the one-on-one contact with the object out of context that sparks those deeply personal and delightfully enchanting experiences.

A hocus-pocus history…

The history of the glass lantern photograph is rooted in magic, but of a much less soothing sort. Before the development of photography, an early type of image projector was invented in the 17th century called the Magic Lantern. Within the lantern was a small concave mirror and a light source that directed light through a small rectangular piece of glass—the lantern slide—and onward into a lens at the front of the device. Whatever images were painted in transparent color on the lantern slide would be enlarged and projected onto a blank wall or screen. Magic was not only in the name as these apparatuses became most famous for displaying monstrous images of the occult: the Devil, spooky apparitions, and ghostly figures. The public of the 17th century was not as accustomed to the phenomena of photography and cinematography as we are today; these visions seemed realistic and bewildering. As early as the 1650s, the Magic Lantern was being used by conjurers and magicians to show frightening images, make things appear and disappear, animate inanimate objects, and summon ghosts of the dead. During the 18th century came the rise of Romanticism and the Gothic novel and with them, an obsession with the bizarre and supernatural. Illusionists Paul Philidor and Johann Georg Schropfer used the Magic Lantern to perform séances of revolutionary figures and apparate ghosts upon request. Etienne-Gaspard Robert was another famous conjurer who, around the 1780s, staged elaborate phantasmagorias at Pavillon de l'Echiquier in Paris. Robert projected supernatural images onto a hanging gauze screen, making the projections appear to be floating midair and giving them a more frightening sense of realism. He would use multiple mechanical slides to make the images move such as having one that shows the face of a phantom and another which had the image of just the eyes to gain the effect of the eyes rolling back and forth. These shows were extremely successful and eventually the trend moved to England where they were received with equal awe and fear.

From supernatural to studious and quite natural…

Tastes changed away from the uncanny and occult, lantern slides became used more widely for educational purposes and eventually for projecting photographic images. The introduction of lantern slide photographs came in 1849, ten years after the invention of photography. Philadelphia daguerreotypists William and Frederick Langenheim looked for a medium that, unlike opaque daguerreotypes, could be projected and largely displayed. They used the discoveries of French inventor Neipce de St. Victor, who discovered a method of adhering light sensitive solution onto glass to create a negative. The Langenheims printed that negative onto another sheet of glass, rather than paper, to make a positive image. The brothers named the invention the Halyotype—halyo is the Greek word for glass—and had it patented in 1850. That following year, they received a medal at the Crystal Palace Exposition in London. They had intended for the slides primarily to be used for entertainment but their applicability to education later revolutionized visual learning. Lecturers of biology and art history gained the invaluable ability to project images of specimens and art from around the world. Lantern slides were used throughout the nineteenth century and well into the first half of the twentieth. A 1937 article from a professor at Dean University notes "...a marked increase in the use of visual aids to education." These aids took two forms, the motion picture and lantern slide photography. The professor writes that motion pictures should only be produced by professionals in the field, but the production of lantern slides is "...a simple task for anyone with a working knowledge of photography. The necessary materials are few and inexpensive." Thus, lantern slides remained quite popular in academia until around 1950 when smaller transparencies became available. The invention of the Kodachrome three-color process that could make 35mm slides remarkably cheaper than lantern slides officially marked the end of lantern slide use aside from as the family heirloom or archival cabinet-fillers.

Tastes changed away from the uncanny and occult, lantern slides became used more widely for educational purposes and eventually for projecting photographic images. The introduction of lantern slide photographs came in 1849, ten years after the invention of photography. Philadelphia daguerreotypists William and Frederick Langenheim looked for a medium that, unlike opaque daguerreotypes, could be projected and largely displayed. They used the discoveries of French inventor Neipce de St. Victor, who discovered a method of adhering light sensitive solution onto glass to create a negative. The Langenheims printed that negative onto another sheet of glass, rather than paper, to make a positive image. The brothers named the invention the Halyotype—halyo is the Greek word for glass—and had it patented in 1850. That following year, they received a medal at the Crystal Palace Exposition in London. They had intended for the slides primarily to be used for entertainment but their applicability to education later revolutionized visual learning. Lecturers of biology and art history gained the invaluable ability to project images of specimens and art from around the world. Lantern slides were used throughout the nineteenth century and well into the first half of the twentieth. A 1937 article from a professor at Dean University notes "...a marked increase in the use of visual aids to education." These aids took two forms, the motion picture and lantern slide photography. The professor writes that motion pictures should only be produced by professionals in the field, but the production of lantern slides is "...a simple task for anyone with a working knowledge of photography. The necessary materials are few and inexpensive." Thus, lantern slides remained quite popular in academia until around 1950 when smaller transparencies became available. The invention of the Kodachrome three-color process that could make 35mm slides remarkably cheaper than lantern slides officially marked the end of lantern slide use aside from as the family heirloom or archival cabinet-fillers. Buried deep in one of these archival cabinets at the Yosemite Museum is a remnant of the magic the bred the medium. At one glance, a supernatural image of blissful levitation; at another, a profoundly quiet moment in the snow. Both are the thrill of art, the thrill of finding something that leaves us changed, quiet, maybe a little scared, and utterly enchanted.