Amongst the trudging bears, thumping deer, and howling coyotes, a quiet creature floats through Yosemite. The butterfly is a silent beauty, gliding with soft bounces through the valley and alpine backcountry. Though most alpine butterflies have a lifespan of only two to four weeks, they leave a lasting impression on the entire park.

and howling coyotes, a quiet creature floats through Yosemite. The butterfly is a silent beauty, gliding with soft bounces through the valley and alpine backcountry. Though most alpine butterflies have a lifespan of only two to four weeks, they leave a lasting impression on the entire park.

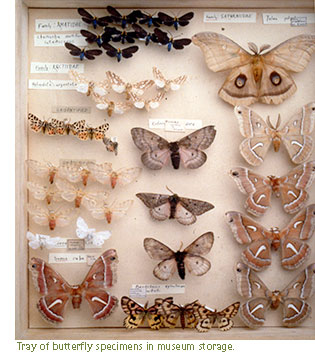

There are loads of them. The Yosemite Museum has specimens, as well as ephemera, t-shirts, patches, belts, photographs, and paintings with brightly colored butterflies emblematic of the region. The living animals are even more prolific. Insects are the most abundant animal species in Yosemite and in the world. Luckily, they're not all creepy crawlers. One of the more elegant of the bugs, butterflies are the most studied insect in the park, and for good reason. Butterflies have been amazing visitors to the Sierra Nevada since Gabriel Moraga's expedition into California in 1806. In fact, the swarms Moraga encountered are the reason for the name of Mariposa County, which is Spanish for "butterfly." Later, another famous traveler became entranced by the winged creatures. John Muir gushes at the sight them in My First Summer in the Sierra (1911):

Butterflies colored like the flowers waver above them in wonderful profusion, and many other beautiful winged people, numbered and known and loved only by the Lord, are waltzing together high over-head, seemingly in pure play and hilarious enjoyment of their little sparks of life. How wonderful they are! How do they get a living, and endure the weather? How are their little bodies, with muscles, nerves, organs, kept warm and jolly in such admirable exuberant health? Regarded only as mechanical inventions, how wonderful they are! Compared with these Godlike man's greatest machines are as nothing. (214-5)

Muir was fascinated by their mechanisms, agility, and grace. Later, a butterfly found in the Sierra Nevada that was one of the several species collected by Muir, the Thecla muirii, was named after him. The same wings, poised and beautiful, that drove Muir to poetry have had an enormous impact on art both within and beyond Yosemite.

Artful creatures…

The vivid insects have inspired art and literature across centuries and continents. Butterflies appear in the archeological record as early as 1350 BCE in Thebes, Egypt. On the tomb painting Nebamun Hunting in the Marshes, the hunting party and flocking birds are surrounded by vast swarms of butterflies. Mesoamerican temples featured brilliantly colored butterflies on temples, buildings, and jewelry. The butterfly in the mouth of a jaguar symbolized war or suffering to some Mayan and Zapotec peoples. Moving into the Renaissance, butterflies could symbolize artistic freedom and capricious creativity. In the painting Jupiter Painting Butterflies, Mercury and Virtue (1522-24) by Italian artist Dosso Dossi, the god Jupiter sits painting butterflies that, with his divine stroke, come to life off the canvas. He is hunched with his head lolled to the side, almost enchanted by the peaceful task as Mercury gestures to the allegorical figure of Virtue to be quiet. The moment of creativity—of artful creation—is more precious than virtue. Fast forward to the late nineteenth century and butterflies still flutter about the canvas as forces of freedom and tranquility. Though far from a tranquil painter, Vincent van Gogh was fascinated by the transformative possibilities of butterflies. He wrote often to his sister Wilhelmina of the exciting and hopeful capability of metamorphosis, which could come without knowing; like how the caterpillar does not know of his future as a butterfly. In 1889 and 1890, Van Gogh made the series, Butterflies of at least four paintings of the insect and one of a moth. Only a few years later, basket weavers on the other side of the world, in Yosemite Valley, were using butterflies to mark another type of transformation.

Weaving wings on the winds of change…

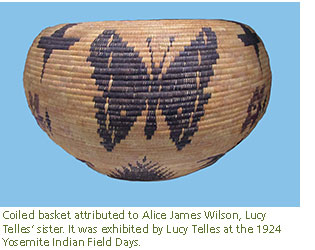

From 1908 to 1920, basket weavers of the Yosemite region, like butterflies themselves, underwent a metamorphosis. The idea had been crystalizing since the 1890s, when weavers began to adapt to a new market of collectors and tourists. Previously, baskets had been relatively simple in design and construction. Traditional patterns woven into baskets in the Yosemite area were typically geometric and formed of lines, squares, bars, triangles, and rectangles. But as more and more tourists and collectors flooded the park to buy baskets, the designs suddenly became more intricate, elaborate, and at times, commercial. Galen Clark recognized some of the new designs as ones you could "see in print," such as published needlework or embroidery designs. It was a time of remarkable innovation of the weavers, one of whom was particularly prolific in her creative designs, Lucy Telles. Telles produced stunning baskets in novel shapes and cutting-edge designs. She included flowers, flames, complex geometric motifs, designs previously only seen in beadwork, and of course, butterflies. Her butterfly baskets are perhaps some of the most beloved in the Yosemite Museum collection with their whimsical and beautiful wings dotting the sides of the magnificent objects. Today, we can see these butterflies as Van Gogh did, as a sign of change. They mark a transformation into a new florescent burst of creativity, one that still brings a joy and Muir-like awe to our spirits.

From 1908 to 1920, basket weavers of the Yosemite region, like butterflies themselves, underwent a metamorphosis. The idea had been crystalizing since the 1890s, when weavers began to adapt to a new market of collectors and tourists. Previously, baskets had been relatively simple in design and construction. Traditional patterns woven into baskets in the Yosemite area were typically geometric and formed of lines, squares, bars, triangles, and rectangles. But as more and more tourists and collectors flooded the park to buy baskets, the designs suddenly became more intricate, elaborate, and at times, commercial. Galen Clark recognized some of the new designs as ones you could "see in print," such as published needlework or embroidery designs. It was a time of remarkable innovation of the weavers, one of whom was particularly prolific in her creative designs, Lucy Telles. Telles produced stunning baskets in novel shapes and cutting-edge designs. She included flowers, flames, complex geometric motifs, designs previously only seen in beadwork, and of course, butterflies. Her butterfly baskets are perhaps some of the most beloved in the Yosemite Museum collection with their whimsical and beautiful wings dotting the sides of the magnificent objects. Today, we can see these butterflies as Van Gogh did, as a sign of change. They mark a transformation into a new florescent burst of creativity, one that still brings a joy and Muir-like awe to our spirits.

Learn more on how to help take part in preserving Yosemite's butterflies.