The state of California was built on the idea that there was something special waiting to be dug up from its soil. Almost the entire state was thought to be hiding treasure beneath its rocky surfaces. And though this dream has long since faded, to a curious intern, the Yosemite Research Library is a gold mine. It sits small and cozy on the second floor of the Yosemite Museum, its rolling shelves swallowing or opening up pathways that—unlike the gray granite walls lining the trails of the Valley just outside—are striated by brightly-colored volumes. Embedded in these walls are pages and pages on everything Yosemite: insects, wildflowers, poetry, anthropology, you name it. There, glinting with the coy allure of a precious metal, is a rather curious and seemingly out of place element of Yosemite history—a chunk of Renaissance England.

In all honesty, I was pretty confused when I stumbled across photographs of court jesters and medieval feasts in the same cabinet as photos of black bears and Yosemite Indians. But when I looked closer, I found familiar faces (Don Tresidder in polyester? Ansel Adams hoisting a ham?) and an even more familiar setting. I had discovered the Bracebridge Dinner.

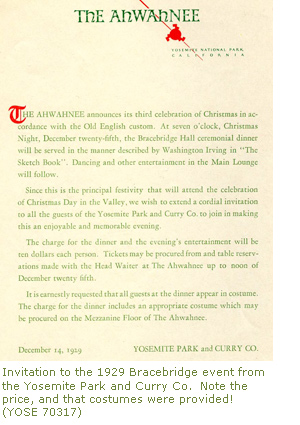

For almost every single year since 1927 (floods washed out one or two and World War II canceled four), The Ahwahnee in Yosemite Valley has hosted an elaborate and fanciful feast around Christmastime known as the Bracebridge Dinner. After months of administrative, culinary and musical preparation, The Ahwahnee presents its guests with a night of fanfare. It opens with heralding trumpets and carries on through multiple courses of food accompanied by singing, acting, and entertaining performances. Each dinner is three hours of holiday magic. And though at high cost, seats at the Dinner are in high demand. For many years, potential guests had to enter a lottery to purchase tickets. But to some, the mythic ideals of old English hospitality, warm-hearted customs, and the blessings of community tradition have no price.

A Literary Tradition

The tradition began with Don Tresidder's infectious passion for festivity. Tresidder, president of Yosemite Park and Curry Company, wanted the newly-created and only luxury hotel in Yosemite, The Ahwahnee, to celebrate its first Christmas with magnificence and spirit. On each menu read: "This year with its first Christmas fire burning upon the hearth at The Ahwahnee, we hope that the spirit of the olden Christmas may find here an abiding place that the warmth of our Yuletide cheer may be kept aglow in your hearts, to bring you back to welcome another Christmas in Yosemite." After the first year's event, Tresidder wanted an even more dramatic experience, so he hired a professional dramatist, Garnett Holme. Holme used a piece of classic literature, The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., by Washington Irving as a basis for the kind of atmosphere he wanted to create. In a series of five vignettes in the book, the character Squire Bracebridge hosts the fictional narrator Geoffrey Crayon for a jovial and sumptuous Christmas feast. Using his characteristic charm, Irving idealizes old English traditions to create an atmosphere of holiday warmth, one that the Bracebridge Dinner tries to emulate to this day. At The Ahwahnee's feast several characters from the story are acted out before the guests, including the Squire, his Lady, the Parson, and the Lord of Mischief, among others. These roles were played by prominent members of the Yosemite community. Most notably, Don Tresidder enthusiastically took on the role of Squire each year and his wife, Mary Curry, served as his Lady. Ansel Adams flexed both his skill in photography and his love for music for many decades as the musical director and photographer.

Renaissance Man

Many of the Museum's Bracebridge photographs were taken by Adams. Although these photos depict quite silly scenes—overly-excited singers and Don Tresidder hopping around goofily in costume—they have the same reverence for Yosemite that Adams is so famous for. They show a photographer so personally intertwined with the place that his work, whether taken while climbing Half Dome or prancing about in medieval costume, is tinted with adoration and emotional connection to Yosemite.

Bracing through War

Like Adams, Yosemite guests and residents developed deep emotional attachments to the Bracebridge Dinners and perhaps the most emotional Dinner was in 1948. The 1948 Bracebridge Dinner came after a period of local and global destruction. As America watched a second World War tear nations apart, residents of Yosemite watched The Ahwahnee transform from an elegant and comfortable hotel to a stripped and sterile Navy hospital. As per the order of Admiral Edgar Woods, Chief Medical Officer of the Twelfth Naval District, The Ahwahnee was commissioned as a wartime hospital. Given no choice, the hotel hosted its last civilian guests on May 30, 1943. On that day, in fact, the first sailor, a maintenance man, landed at the hotel, followed by a larger group of hospital corpsmen on June 7.

The period of naval presence could be considered a disaster to archivists and art historians. Much of the grand furniture was damaged. The artifacts and décor that were removed for preservation placed onto railway cars to be sent to Oakland for storage, but a train wreck sent seven cars into the Merced River. The character of The Ahwahnee took a dark turn. The hotel was commissioned as a special hospital on June 25, 1943, and on July 7, its first neuropsychiatric patients arrived. Neither they, nor the subsequent non-neuropsychiatric patients appreciated the Sierra environment. They found themselves bored, isolated, claustrophobic, and depressed. The high mountain walls and quiet scenery were far from the girls, beer, and liberty they craved and expected. Yosemite was "surrounded by solitude," in the words of one patient. By the time the Navy had evacuated the hotel at the war's end in 1945, there was a visceral change in the building. The miserable spirits of the soldiers, paired with the damaged furniture and decorations left The Ahwahnee empty in hall and heart.

The Navy paid $175,700 dollars for restoration, but Tresidder knew that the spirit would need more than money to be rebuilt. Just like the grand opening of The Ahwahnee on July 14, 1927, Tresidder designed the first celebration of the reopening exclusively for local residents, "those who have helped physically and spiritually with the job of restoring The Ahwahnee." Soon after, the Ahwahnee welcomed its first peacetime guests and celebrated a momentous Bracebridge Dinner. The decision to put on the Bracebridge was made only in mid-November, leaving little time to prepare. Ansel Adams, whose photography career was blossoming, hired Eugene Fulton as musical director to ease the pressure of short notice. He forecast "it's going to be a GOOD Bracebridge," and afterward, proudly assessed, "It was a grand affair...gratifying beyond expectations." Don Tresidder played his signature role of Squire Bracebridge with gusto. It seems that through this so out-of-place, silly, extravagant event, the type of feelings Tresidder and Irving were kindred in chasing were tangible: warmth, community, and joy.

Yet this Dinner would also be memorable for more tragic reasons. The 1948 Bracebridge would be Don Tresidder's last. Only a few weeks after, Tresidder, 52, died suddenly of a heart attack while visiting in New York. The Yosemite community was shocked and heartbroken. Heated debates ensued over whether or not the role of the Squire should be eliminated from the show—the character and Tresidder were so intricately associated, people had started calling Tresidder the Squire of Yosemite. Eventually, as per the suggestion of Ansel Adams, the character of the Squire was kept and was to be played by various dramatists from Stanford (Tresidder was president of Stanford University from 1943 to 1948) but his role in the narrative and those of his family would be diminished. Aside from these changes, the traditional Bracebridge Dinner continues to this day with the welcoming and enthusiastic spirit Tresidder so passionately embedded in it.

Yet this Dinner would also be memorable for more tragic reasons. The 1948 Bracebridge would be Don Tresidder's last. Only a few weeks after, Tresidder, 52, died suddenly of a heart attack while visiting in New York. The Yosemite community was shocked and heartbroken. Heated debates ensued over whether or not the role of the Squire should be eliminated from the show—the character and Tresidder were so intricately associated, people had started calling Tresidder the Squire of Yosemite. Eventually, as per the suggestion of Ansel Adams, the character of the Squire was kept and was to be played by various dramatists from Stanford (Tresidder was president of Stanford University from 1943 to 1948) but his role in the narrative and those of his family would be diminished. Aside from these changes, the traditional Bracebridge Dinner continues to this day with the welcoming and enthusiastic spirit Tresidder so passionately embedded in it. For some, this rich piece of history is tasted every holiday season. For others, it's lived vicariously through stories, Facebook posts, or travel websites. For me, it started as something glinting in the walls of the Library;a fleck that led to an intriguing nugget—one that seemed at first so out of place but now seems so perfectly and naturally a part of Yosemite.

Learn more about the current Bracebridge Dinner.