I like to doodle in class. Lots of people do. When I doodle, I feel this freedom that comes only in knowing that no one else is ever going to see it; that only the nosy kid peeking over at my desk will ever know about the tiny world I've whipped together in the margin of my college-ruled notebook. Maybe Thomas Moran felt the same. Except unlike being crushed between coffee-stained pages that are likely starting to mold in a cardboard box in my basement, Moran's sketches are on display in museums all over the country, from the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., to the Yosemite Museum in California. And even though he never intended for many of the sketches to be seen, they give us something no finished piece can, something poetic and something raw.

The Dangers in Consuming Raw and Undercooked

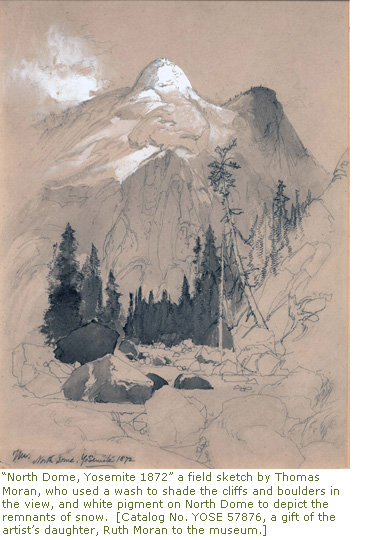

Of course, raw isn't for everyone. It certainly wasn't how Moran or his contemporaries preferred their paintings. In his time, the piece currently at the Yosemite Museum would never have made it to show even if Moran had wanted it to. The 19thcentury boiled in debate over the merits of sketched or unfinished works, which spilled over into the controversy of valuing watercolors next to the prestige of oils. While these debates were focused in France and England, they were pertinent to American landscape artists like Moran who looked to British artists like J. M. W. Turner for mentorship and inspiration. Watercolors were criticized for looking too unfinished, too sketched with their quick, sweeping brushstrokes and thin transparency. Even at the time of Moran’s death, though there were plenty of exhibitions devoted exclusively to watercolors, the majority of artists and critics saw the medium as inferior to oils. Even less dignified were unfinished pieces, especially unfinished watercolors. For most artists, watercolor sketches were largely just tools to later create other—usually larger and painted in oil—paintings. Moran used sketches even less than most of his contemporaries and, rather than seeing them as a base or template for another picture, he used them to spark his memory of a place so he could create an image anew. Strict accuracy was hardly his goal. Rather, he wrote, “While I desire to tell truly of Nature, I do not wish to realize the scene literally, but to preserve and convey its true impression.” Moran, like Ansel Adams and countless other artists after him, saw the canvas as a place for showing the reaction of an artist—of a person—to the magnificent scenes before him. The sketches he made were to bring him back to those visceral scenes. This, paired with a highly-trained visual memory, led to the creation of the masterful finished works we are familiar with today. Moran used sketches as tools along the way, steps upon the path. But for some, even these steps could be beautiful.

Of course, raw isn't for everyone. It certainly wasn't how Moran or his contemporaries preferred their paintings. In his time, the piece currently at the Yosemite Museum would never have made it to show even if Moran had wanted it to. The 19thcentury boiled in debate over the merits of sketched or unfinished works, which spilled over into the controversy of valuing watercolors next to the prestige of oils. While these debates were focused in France and England, they were pertinent to American landscape artists like Moran who looked to British artists like J. M. W. Turner for mentorship and inspiration. Watercolors were criticized for looking too unfinished, too sketched with their quick, sweeping brushstrokes and thin transparency. Even at the time of Moran’s death, though there were plenty of exhibitions devoted exclusively to watercolors, the majority of artists and critics saw the medium as inferior to oils. Even less dignified were unfinished pieces, especially unfinished watercolors. For most artists, watercolor sketches were largely just tools to later create other—usually larger and painted in oil—paintings. Moran used sketches even less than most of his contemporaries and, rather than seeing them as a base or template for another picture, he used them to spark his memory of a place so he could create an image anew. Strict accuracy was hardly his goal. Rather, he wrote, “While I desire to tell truly of Nature, I do not wish to realize the scene literally, but to preserve and convey its true impression.” Moran, like Ansel Adams and countless other artists after him, saw the canvas as a place for showing the reaction of an artist—of a person—to the magnificent scenes before him. The sketches he made were to bring him back to those visceral scenes. This, paired with a highly-trained visual memory, led to the creation of the masterful finished works we are familiar with today. Moran used sketches as tools along the way, steps upon the path. But for some, even these steps could be beautiful.

To a small number of artists and critics, the very qualities that made watercolors so heretical also made them uniquely powerful. The quick lines were spontaneous, the transparency was soft and beautiful, and the combination created a directness that can be coldly distilled by the meticulous planning of oil painting. Moreover, the unfinished watercolor sketch offered intensified directness to the artist’s hand, the feeling of his own presence both at the scene and on the page. This sentiment was echoed in Moran’s time by critics such as S.S. Conant, who agreed with the modern supposition that “there is a certain charm about a master’s sketch which no finished picture has—a freshness, a vividness of idea, and a truth in nature, often left out when the work is elaborated with art and science in the studio.” Most Americans today would agree. We want to see the genesis of the idea, the working out of the form, the little bits of process that are hidden by a final painting. We want to see the artist informal, bare, and utterly human. We are fascinated by the drafts and sketches of our favorite artists, from theirplein airlandscapes to their margin doodles.

Unintended Side Effects

As museums display the sketches—elegantly framed, lit from above and shouldered by small, carefully worded labels—they take on a role beyond just artifacts of an artist’s process.North Dome, now on display at the Yosemite Museum, carries as much richness, beauty, and lyric symbolism as if it were complete. While Moran is known for painting Yellowstone, and in fact was instrumental in getting Yellowstone National Park established, he spent some time at Yosemite, and this painting is a brief and rare glimpse at the park through his brush. Though obviously incomplete and not intended by the artist, the image resonates with the diversity and harmony of Yosemite. Immediately, the stark contrast of the chalky snow white across the top of the Dome with the dark blacks of the trees and rocks beneath it creates a sense of balance. The space between the two poles is left uncolored, an invitation for us to fill it with all the gradients that fall between. The space is a closed circuit that circles round from the dipping bowl of the dark treetops to the light downward curve of the Dome. The symmetry and movement of nature is effortless. It is a system in concert with itself, moving harmoniously in its cadence from forest floor to snowy mountain peak. This sketch seems an accurate mirror of Yosemite, a park characterized by fluctuating waterfalls and dynamic diversity of landscape. Both painting and park beg the visitor to fill in what is left unfinished, to add what Yosemite looks like through their eyes, what each shade and shape means to them personally. As the circle of ink and watercolor continually flows, the park gently circles through cycles of visitors and seasons. The park is never finished; it continues in its harmony, peacefully doodling.

As museums display the sketches—elegantly framed, lit from above and shouldered by small, carefully worded labels—they take on a role beyond just artifacts of an artist’s process.North Dome, now on display at the Yosemite Museum, carries as much richness, beauty, and lyric symbolism as if it were complete. While Moran is known for painting Yellowstone, and in fact was instrumental in getting Yellowstone National Park established, he spent some time at Yosemite, and this painting is a brief and rare glimpse at the park through his brush. Though obviously incomplete and not intended by the artist, the image resonates with the diversity and harmony of Yosemite. Immediately, the stark contrast of the chalky snow white across the top of the Dome with the dark blacks of the trees and rocks beneath it creates a sense of balance. The space between the two poles is left uncolored, an invitation for us to fill it with all the gradients that fall between. The space is a closed circuit that circles round from the dipping bowl of the dark treetops to the light downward curve of the Dome. The symmetry and movement of nature is effortless. It is a system in concert with itself, moving harmoniously in its cadence from forest floor to snowy mountain peak. This sketch seems an accurate mirror of Yosemite, a park characterized by fluctuating waterfalls and dynamic diversity of landscape. Both painting and park beg the visitor to fill in what is left unfinished, to add what Yosemite looks like through their eyes, what each shade and shape means to them personally. As the circle of ink and watercolor continually flows, the park gently circles through cycles of visitors and seasons. The park is never finished; it continues in its harmony, peacefully doodling.