A passionate perspective

A passionate perspective Artistic energy practically bursts from his penstrokes. Though born in Uruguay and raised in New England, Joseph Jacinto Mora was always fascinated by the American west. After studying art in Boston and New York, Mora left the east to work as a wrangler and cow puncher in Texas. He eventually made his way to California and by 1924, was teaching art classes and installing his own works in Carmel, such as a sarcophagus for Father Junipero Serra at Carmel Mission. Like his map of Yosemite, his mediums were colorful and diverse. While in Carmel, he worked on architectural elements for city buildings nationwide and made advertising for local businesses (menus for Pop Ernest's Seafood in Monterey, ads for Hotel del Monte and the Carmel Dairy). He even made an advertisement for Yosemite featuring a landscape drawing of the Valley behind a line of animals in full mountain clothes enjoying a campfire, the smoke of which shows guests delighting in park activities. He made watercolor and pen and ink landscape drawings, he illustrated books, and authored three himself: A Log of the Spanish Main (1933), Trail Dust and Saddle Leather (1946), and his posthumous publication Californios(1949). But he is best known for his maps, or cartes as he titles them. Each, though bursting with humor and color, remains accurate to the geography of the sites: Carmel, Los Angeles, San Diego, and of course, Yosemite.

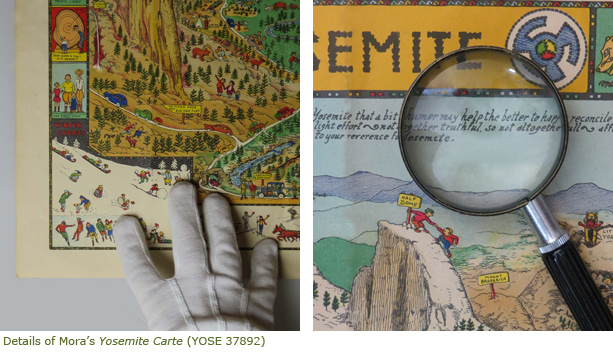

Those familiar with the park will find the Yosemite map shockingly accurate not just in landmark formations, but also in its caricatures of the park's human life. The familiar and comical vignettes cover all kinds of visitor mayhem, from having no money at a checking station and doing make-up in Mirror Lake, to the all too common stink-face of a child groaning against the excitement of his wide-eyed parents. Visitors in cars have long and distorted necks that crane impossibly to see the views. Bears chase down tourists, luxuriate in fine dining, and pose for photographs. Tourists scornfully hush one another as they approach a cloud sleeping in a chair at the top of Cloud's Rest. Green aliens dance at the bottom of Vernal Falls. Along the left border and bottom left corner of the poster, small boxes house animated renderings of the activities and amenities the park has to offer, from dancing bowling pins to luxurious swimming pools. Mora captures, reimagines, and exaggerates the life of Yosemite. He seems to have an insider's sense of humor, which is why the poster is a favorite among park staff. This familiarity with the park that we feel coming from Mora's pen could stem from his visit to the park in 1904. Proudly across the top of the map, Mora's note of intention indicates how he felt the weight of Yosemite:

"There is so much Grandeur and reverential Solemnity to Yosemite that a bit of humor may help the better to happily reconcile ourselves to the triviality of Man. Give me the souls who smile at their devotions! Now, should this light effort—not altogether truthful, so not altogether dull—afford you a tithe of mirth, I shall feel I have added to your reverence for Yosemite."

The Real Yosemite—Where's Waldo Emerson?

Mora admits that the map is not "altogether truthful." Clouds, unfortunately for eager meteorologists, do not sit in armchairs. But Mora does hit on something very real in Yosemite: its spirit.

Mora's dancing cartoons breathe playful levity upon a place so often weighted by the heavy significance of words like "transcendence." He takes a history of erudite musings on nature, from Emerson to Thoreau and Muir, and brightens them up with eye-popping color and outlandish cartoon figures. He plucks the granite mammoths—ones that have guarded this landscape solidly for thousands of years—and scrambles them onto a whimsical game-board. He dyes the sacred and millennial-old earth-tones with colors we see on our Sunday comic strips. The park becomes alive and modern;it becomes accessible. It is not a heady revelation or a flexing of masterful skill. It is easy, fun, and for everyone to enjoy. His approach does not attempt to capture what is visually real—he doesn't meticulously render every leaf or crag of granite—but Mora's large cartoon is real all the same. It embodies the humor of the park's people. It renders the spirit of its visitors, adventurers, and employees across 150 years. Mora shows a willingness to not take things too seriously and to accept the wilderness as not just a place for the most profound intellectual, philosophical, or religious revelations of Yosemite's famous figure-heads. It can be a place for fun, a place for people. The map shows easy to understand and lighthearted visual puns for almost every landmark: George Washington atop Washington Column, a bride tip-toeing on Bridalveil Fall, a maritime captain proud on El Capitan. The park is literally made of people. Men and women are a part of the park just as much as every gargantuan rock formation and mesmerizing waterfall. As we all watch Yosemite Falls slowly drying up, Mora reminds us that Yosemite's spirit still has a bountiful and fun reservoir.

Part of this spirit is fueled by the park's unique ability to ignite personal connections. For some, the park is a place to be alone in nature and find moments of quiet transcendence. For them, throngs of tourists are a disaster to their image of the real Yosemite. But Mora relishes in the noise. He paints a very different, perhaps more real experience of Yosemite: a place thriving—beautifully—with human life. The Where's Waldo cast-of-thousands is not chaotic or crowded, but rather exciting and adventurous. It becomes a game to look for all of the characters and figures, to discover what words or trends they're playing off of. When we giggle at the cumulus lounging atop Cloud's Rest, we are taking part in one of the most magical elements of the park: sharing. We share a moment with Mora;we're in on his joke. Experience with Yosemite is the bridge for this connection. As we share these indescribable acres of land with one another, whether by hiking with housemates, leading wilderness tours, or photo messaging our east coast cousins, we are creating the spirit that Mora captures so capriciously: the thorough invigoration of connecting with one another as we share Yosemite.

Part of this spirit is fueled by the park's unique ability to ignite personal connections. For some, the park is a place to be alone in nature and find moments of quiet transcendence. For them, throngs of tourists are a disaster to their image of the real Yosemite. But Mora relishes in the noise. He paints a very different, perhaps more real experience of Yosemite: a place thriving—beautifully—with human life. The Where's Waldo cast-of-thousands is not chaotic or crowded, but rather exciting and adventurous. It becomes a game to look for all of the characters and figures, to discover what words or trends they're playing off of. When we giggle at the cumulus lounging atop Cloud's Rest, we are taking part in one of the most magical elements of the park: sharing. We share a moment with Mora;we're in on his joke. Experience with Yosemite is the bridge for this connection. As we share these indescribable acres of land with one another, whether by hiking with housemates, leading wilderness tours, or photo messaging our east coast cousins, we are creating the spirit that Mora captures so capriciously: the thorough invigoration of connecting with one another as we share Yosemite.