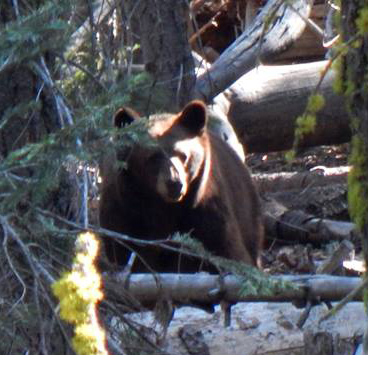

At Yosemite, arguably the most iconic and charismatic of all wildlife present is in fact the American black bears. Often most active in the evening and not uncommonly found foraging in the concealment of the high branches of an apple tree, the bears rarely present themselves in broad daylight or out in the open for the appreciation of the thousands of amateur photographers here. Nevertheless, the mere rumor that there might be a bear in the area is enough to gather a small throng and snarl traffic for miles as motorists crane their necks for the most fleeting of looks at the image of a bear. As a park ranger, these opportunities, sometimes called "animal jams," can be extremely gratifying when such sightings allow for us to interact with hundreds if not thousands of park visitors and provide them greater knowledge and insight into the natural history of our wildlife. At the same time, these jams can also be also be monumentally frustrating as visitors sometimes stall traffic or attempt to approach a wild animal closer than what is considered safe.

In both such instances I've often reflected that most visitors could easily see the same animal much closer up in the safe confines of a zoo. However, I've noticed how people react differently to animals in zoos versus animals here in the wild. I've been to plenty of zoos where most people take a cursory look, wonder where the animals are (usually sleeping) and move on, whereas at many national parks (for good or ill) you will have the aforementioned throngs of people clustered around massive telescopes just to get a parting glance at some charismatic animal. When the animal in the zoo and the animal in the park is the same one, for instance when it comes to bears, why is there the different attitude? Perhaps this differing of attitudes might partially explain why some visitors come here to Yosemite and not go to a zoo or a theme park. People want to experience something truly wild here, something apart from our highly structured and ordered, some might say overly-civilized, and increasingly urbanized world.

There is something intrinsically thrilling about seeing wild bears, not caged bears, for many reasons, for we enjoy a deep cultural connections to bears, a connection that goes back to our shared primordial past. While thinking of bears at our national parks I'm reminded of a quote from Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad:

There is something intrinsically thrilling about seeing wild bears, not caged bears, for many reasons, for we enjoy a deep cultural connections to bears, a connection that goes back to our shared primordial past. While thinking of bears at our national parks I'm reminded of a quote from Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad: "We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there —there you could look at a thing monstrous and free."

I'm not trying to suggest bears are monsters, not in the traditional sense of boogeymen hiding under a bed. However, in some ways they are monstrous; huge, powerful, clawed, intelligent, independent of our society and our rules, both in the dark recesses of our forests and our imaginations, and indeed here in Yosemite they do live free. They are also somewhat human-like in many regards, or more properly, we humans have a tendency to project human values and attributes onto them, which in turn can either make them seem scarier or cuter.

Not surprisingly, human beings have an incredible cultural connection to bears. Bears were found on every continent inhabited by people but Australia (sadly, the brown bear is now completely extirpated from North Africa but was present until historical times). Many human cultures have identified a distinct connection between ourselves and bears, and some claim direct ancestry from bears. Apart from being powerful (an attribute that has always appealed to people), both humans and bears share several distinct overlapping traits;we can both walk upright, both have flat feet and walk directly on our five toes, both are omnivores eating plants/vegetation and animals, and both have pectoral mammary glands;bears are one of the few other mammals other than humans that can nurse from a sitting position.

Therefore, if you came to Yosemite to see a bear that desire is deeply rooted, consciously or not, in thousands of years of our shared human cultural heritage. Seeing a wild bear in Yosemite I believe taps into a deep memory of sharing our world with bears that goes back millennia. The bear, as a widespread, large, powerful, charismatic animal has had an indelible impact on the human experience across continents. Look no further than the engravings done on cave walls that are tens of thousands of years old. Indeed, we may have competed with the prehistoric cave bear for living space. Archeologists have unearthed the remains of bears' bones in caves from prehistoric times. In one cave in Switzerland thousands of bear skeletons have been uncovered. The bones were arranged in ways that could not possibly have been natural. Bear skulls have been found hidden under stone slabs with one bear skull atop a femur bone placed in their center. Whether bears related to some very early religious practice is intriguing but, of course, pure conjecture.

Nonetheless, what is not conjecture is the role that bears played in the oral traditions of cultures that persist to this day. A myth of ancient Japan describes the bear as being a chief god and by eating the flesh of a bear meant one was receiving a gift from heaven. A Korean creation myth relates how both bears and tigers sought to become human beings but only the bear was successful, becoming a woman, marrying the prince of heaven and giving birth to a son who became the first ruler of Korea. The Bible relates the story of when two female bears acted as divine vengeance when they ate up 42 youths who dared make fun of the Prophet Elisha's bald head. Many Native American myths relate to the bear-mother, a young maiden who was captured by the bear-people. One of them, a leader among the bear-people, married her and fathered two sons with her. Those sons would learn all the songs and wisdom of the bears. The father was eventually killed by the brothers of the abducted bear-mother, who either aided their efforts or killed them for it depending on which version you hear. With their deceased father's knowledge, the two sons went forth and spread their father's knowledge about how to hunt and find food (remember bears and humans, both being omnivores, eat many of the same things) and became great leaders. However, upon the death of their mother, the bear- mother, they donned their bear robes and became bears once more.

Another interesting bear myth, especially as it relates to the National Park Service, is one shared by many tribes of the American Great Plains. It describes seven sisters, who, while playing one day, witness their brother turn into a huge and ravenous bear. The sisters ran to a tree stump and, as the terrible bear approached, the stump rose higher and higher into the sky, lifting the sisters away from danger. In anger the bear scored the sides of the stump with his great claws, leaving deep grooves in its side, but by that point his sisters had reached the sky and become the seven main stars of the constellation Ursa Major, often known as the Big Dipper. The clawed stump became a mountain that was known in the Lakota language as "Mahto Tipila" meaning Bear Lodge or Bear Teepee. Naturally, like a lot of Native American names, this name got mistranslated to "Mountain of the Bad God" or rather "Devil's Tower," the very first national monument in the National Park Service, designated by President Theodore Roosevelt himself under the auspices of the Antiquities Act of 1906, an act still used by presidents to this day to designate national monuments.

It is interesting that across continent and nations Ursa Major was seen as a bear figure. Of course Ursa Major itself, which is Latin, means "Big Bear." The name of this constellation's name comes from an ancient Greek myth wherein Zeus, king of the gods, espied the nymph Callisto, a name which means "most beautiful." In disguise Zeus seduced Callisto who eventually gave birth to a son named Arcas, which means "Bear Warden." In a jealous rage, Zeus's wife, Hera, turned Callisto into a bear. Quite by accident one day Arcas spotted his own bear-mother but did not recognize her as such. He was in the act of drawing his bow to slay her when Zeus intervened and did what I guess any normal loving father would do; he turned his son into a bear as well. To keep them from the wrath of Hera, Zeus placed both mother and son into the night sky. The mother became Ursa Major, the "Big Bear" and Arcas became Ursa Minor, the "Little Bear." Arcas also lends his name to the scientific name for the Grizzly Bear; Ursus arctos, a combination of both Latin and Greek to mean "Bear, Bear" (the animal so nice they named it twice). It is fascinating how so many cultures saw Ursa Major as a bear figure or revered the bear as a mother figure; for few animals can be said to be as protective a mother as a bear.

However, more than just as figures in myths or stories, bears need to remain as wild animals. Here in Yosemite they can have the space and habitat to do so because more people would rather see them as wild animals, not inmates behind bars.