NPS / Jim Peaco Although wolf packs once roamed from the Arctic tundra to Mexico, loss of habitat and extermination programs led to their demise throughout most of the United States by the early 1900s. In 1973, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) listed the northern Rocky Mountain wolf (Canis lupus) as an endangered species and designated Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE) as one of three recovery areas. From 1995 to 1997, 41 wild wolves from Canada and northwest Montana were released in Yellowstone. As expected, wolves from the growing population dispersed to establish territories outside the park, where they are less protected from human-caused mortalities. The park helps ensure the species’ long-term viability in GYE and has provided a place for research on how wolves may affect many aspects of the ecosystem. January 12, 2020, marked the 25th anniversary since wolves returned to Yellowstone.

NPS / Michael Warner DescriptionWolves are highly social animals and live in packs. Worldwide, pack size will depend on the size and abundance of prey. In Yellowstone, average pack size is 11.8 individuals. The pack is a complex social family, with older members (often the alpha male and alpha female) and subordinates, each having individual personality traits and roles within the pack. Packs defend their territory from other, invading packs by howling and scent-marking with urine. Research in Yellowstone since reintroduction has highlighted the adaptive value of social living in wolves – from cooperative care of offspring, group hunting of large prey, defense of territory and prey carcasses, and even survival benefits to infirmed individuals. Wolves consume a wide variety of prey, large and small. They efficiently hunt large prey that other predators cannot usually kill. In Yellowstone, 90% of their winter prey is elk; 10–15% of their summer prey is deer. They also kill bison. Many other animals benefit from wolf kills. For example, when wolves kill an elk, ravens and magpies arrive almost immediately. Coyotes arrive soon after, waiting nearby until the wolves are sated. Bears will attempt to chase the wolves away, and are usually successful. Many other animals—from eagles to invertebrates—consume the remains. Since reintroduction, genetic studies have evaluated Yellowstone wolves’ genetic health, kinship within and between packs, connectivity with other Northern Rocky mountain populations, and even genes linked to physical and behavioral traits. One fascinating discovery involves coat color. About half of wolves in Yellowstone are dark black in color, with the other half mostly gray coats. The presence of black coats was due to a single gene (a beta defensin gene termed CBD103 or the K-locus), with all black coated individuals carrying a mutation linked to this coat color - a mutation believed to have originated in domestic dogs of the Old World. The origin of the K-locus in wolves likely came from hybridization between dogs and wolves in northwest North America within the last 7,000 years as early humans brought domestic dogs across the Bering Land Bridge. In Yellowstone, this discovery set the stage for studies that explored the link between coat color, reproduction, survival, and behavior. It was found that the K-locus gene is involved in immune function in addition to causing black coat color, suggesting an additional role in pathogen defense. For example, black wolves have greater survivorship during distemper outbreaks. Another study found gray wolves to be more aggressive than black colored wolves during territorial conflict, as well as have higher reproductive success. During breeding season, there is also greater mate choice between opposite color male and female pairs compared to same colored pairs. Together, these data suggest fitness trade-offs between gray and black coat color, evidence for the maintenance of the black coat color in the population. Changes in Their PreyFrom 1995 to 2000, in early winter, elk calves comprised 50% of wolf prey, and bull elk comprised 25%. That ratio reversed from 2001 to 2007, indicating changes in prey vulnerability and availability. Although elk is still the primary prey, bison has become an increasingly important food source for wolves. While there is some predation on bison of all age classes, the majority of the consumption comes from scavenging winter-killed prey or bison dying from injuries sustained during breeding season. The discovery of these changes emphasizes the importance of long-term monitoring to understand predator-prey dynamics. Changes in wolf predation patterns and impacts on prey species like elk are inextricably linked to other factors, such as other predators, management of ungulates outside the park, and weather (e.g. drought, winter severity). Weather patterns influence forage quality and availability, ultimately impacting elk nutritional condition. Consequently, changes in prey selection and kill rates through time result from complex interactions among these factors. Current National Park Service (NPS) research focuses on the relative factors driving wolf predation over the past 25 years.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

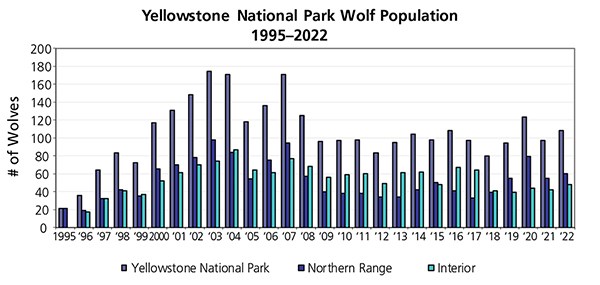

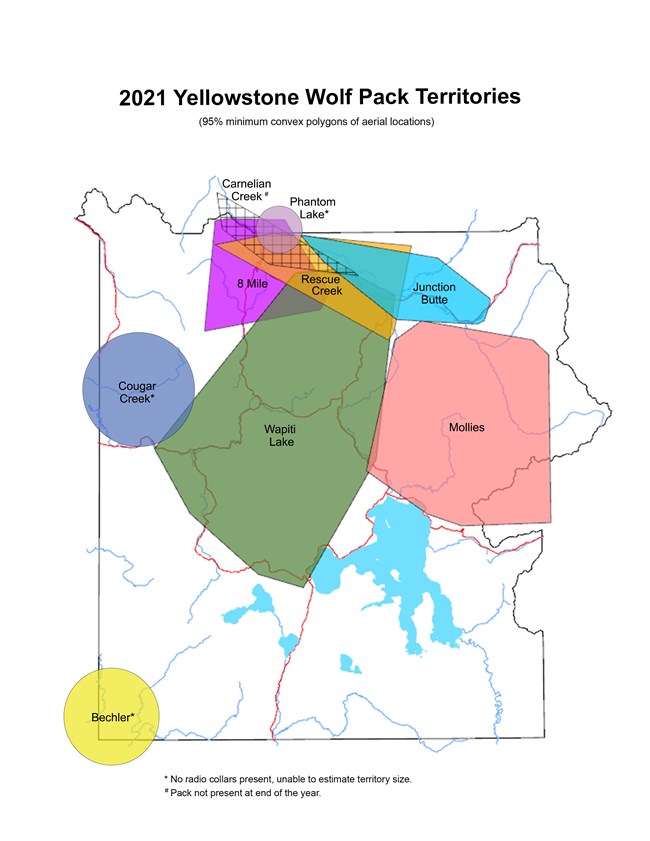

The Northern Range is the hub of wildlife in Yellowstone National Park. Occupying just 10 percent of the park, it is winter range for the biggest elk herd in Yellowstone and is arguably the most carnivore-rich area in North America. Early management of predators caused dynamic changes to the ecosystem. The reappearance of carnivores on the landscape has had significant and sometimes unexpected impacts on the resident grazers and their habitat. PopulationIn the first years following wolf restoration, the population grew rapidly as the newly formed packs spread out to establish territories with sufficient prey. The wolves have expanded their population and range, and now are found throughout the GYE. Disease periodically kills a number of pups and old adults. Outbreaks of canine distemper occurred in 2005, 2008, and 2009. In 2005, distemper killed twothirds of the pups within the park. Infectious canine hepatitis, canine parvovirus, and bordetella have also have been confirmed among Yellowstone wolves, but their effects on mortality are unknown. Sarcoptic mange, an infection caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei, reached epidemic proportions among northern range wolves in 2009. The mite is primarily transmitted through direct contact and burrows into the wolf’s skin, which can initiate an extreme allergic reaction and cause the wolf to scratch the infected areas, resulting in hair loss and secondary infections. By the end of 2011, the epidemic had mostly subsided; however, the infection is still present at lower prevalences throughout the park. Wolf packs are highly territorial and communicate with neighboring packs by scent-marking and howling. Occasionally packs encounter each other, and these interactions are typically aggressive. Larger packs often defeat smaller groups, unless the small group has more old adult or adult male members. Sixty-five percent of collared wolves are ultimately killed by rival packs.

NPS The park’s wolf population has stabilized since 2009 after declines from the initial recolonization. Most of the decrease has been in packs on the northern range, where it has been attributed primarily to the decline in the elk population and available territory. Canine distemper and sarcoptic mange have also been factors in the population decline. Each year, park researchers capture a small proportion of wolves and fit them with radio tracking and GPS collars. These collars enable researchers to gather data on an individual, and also monitor the population as a whole to see how wolves are affecting other animals and plants within the park. Typically, at the end of each year, only 20% of the population is collared. Wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountains have met the FWS’s criteria for a recovered wolf population since 2002. As of December 2015, the US Fish & Wildlife Service estimated about 1,704 wolves and 95 breeding pairs in the Northern Rocky Mountain Distinct Population Segment. The gray wolf was removed from the endangered species list in 2011 in Idaho and Montana. They were delisted in Wyoming in 2016, and that decision was held up on appeal in April 2017. Wolves are hunted in Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana under state hunting regulations.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Wonders abound in Yellowstone, though many come with an unfamiliar danger. Learn how to adventure through Yellowstone safely.

NPS Your Safety in Wolf CountryWolves are not normally a danger to humans, unless humans habituate them by providing them with food. No wolf has attacked a human in Yellowstone, but a few attacks have occurred in other places. Like coyotes, wolves can quickly learn to associate campgrounds, picnic areas, and roads with food. This can lead to aggressive behavior toward humans. What You Can Do

Wolves in Yellowstone occasionally become habituated to human or vehicle noise. Biologists successfully aversive-condition several wolves each year. Visitor education is important to help keep wolves wild and wary of humans. There have been no cases of people injured by wolves in Yellowstone; however, two have been killed (2009 and 2011) when their behavior could not be changed with aversive conditioning. Both wolves were likely fed by people. Current Wolf ManagementWolves are managed by the appropriate state, tribal, or federal agencies. Management authority depends on current status and location of subpopulations. Within Yellowstone National Park, no hunting of wolves is allowed. Outside the park, Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming regulate and manage hunting. Because wolves do not recognize political boundaries and often move between different jurisdictions, some wolves that live within the park for most of the year, but at times move outside the park, are taken in the hunts. For current information about management of wolves around Yellowstone visit US Fish and Wildlife Service's web page on the gray wolf. Wolf FactsSource: Data Store Collection 7753. To search for additional information, visit the Data Store.

Wolf Restoration

1995 marked the year wolves returned to Yellowstone. Learn more about this journey.

Wolf Reports

Since 1995, the Yellowstone Wolf Project has produced annual reports.

Yellowstone Science Issue on Wolves

Check out the Yellowstone Science periodical devoted entirely to wolves.

Gray Wolf Videos

From education videos to raw footage of wolves in the park, explore Yellowstone's collection of wolf films.

Wolf Sounds

Listen to various wolf sounds collected in the park. |

Last updated: October 22, 2024